Clyde Cook could not stop preaching the gospel, even after he was gone.

A week after his death, he was at it once more — this time in a taped farewell to the thousands of people who had gathered for a memorial service to honor his remarkable life.

As his familiar, soothing voice filled the auditorium, Cook marveled at the wonders of his new home: the fine gold, the precious gems, the thunderous worship, the brilliant glory of God.

“Believe me, it’s tearless here,” he told a weeping audience. “And it is all true, every word in the blessed Book. Trust it, and trust our beloved Savior. Don’t be weary in well-doing, as you will reap if you don’t faint.”

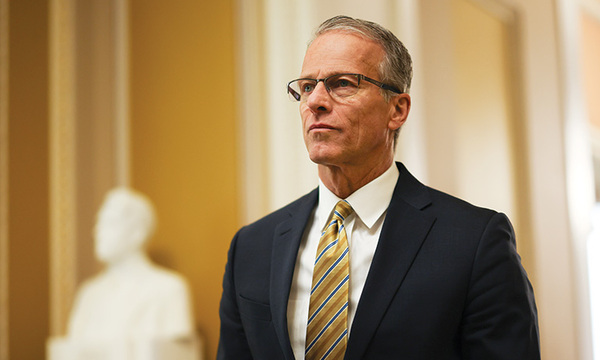

Cook’s death of a heart attack on April 11 — less than a year after he retired as the longest-serving president in Biola’s history — may have come as a shock to many, but he was ready for it. He had spent a lifetime preparing for it.

As a missionary, an educator and ultimately an influential university president, it was his oft-stated goal to invest his time in work that would last for eternity. He yearned for that city whose architect and builder is God, and his life was staked on that hope.

“Clyde knew that once he was with Jesus, there was no way he would want to come back,” said Brian Shook, Cook’s assistant for 14 years. “He lived every day of his life in that expectancy — that every minute mattered, because once his race was finally run he would be in the presence of the Almighty God.”

In his 25 years as the public face of Biola, Cook was an instrumental force in transforming the school from a small Bible college to one of the fastest-growing universities in the nation.

Under his watch, Biola’s size and academic reputation grew dramatically. Enrollment doubled to nearly 6,000 students. Twelve new buildings were added to the campus. Four new graduate schools were launched. The grade point average and SAT score of the average incoming student improved significantly. The operating budget grew by nearly 10 times, putting it among the largest in the Council for Christian Colleges & Universities.

Yet for all the accomplishments, what mattered most to Cook was that Biola held fast to its founding mission of impacting the world for Christ. One of his biggest achievements, he said as he neared retirement, was “maintaining Biola’s spiritual dynamic and not compromising it for the sake of secular academic respectability.”

That steadfast commitment to Biola’s mission of biblically centered education was seen in the major choices Cook made as president: faculty selection, launching of new programs, maintaining of doctrinal standards. But it was also illustrated quite simply in the way he modeled faith and integrity on a daily basis, colleagues said.

“He had a Great Commission perspective that he was able to translate into his daily walk with Jesus,” said Erik Thoennes, a theology professor at Biola. “He was a man who lived for the gospel and lived it in very practical ways. Dr. Cook clearly saw the connection between walking humbly and obediently with his God and being used by him in reaching the nations for Christ.”

Cook quoted Scripture from memory, naturally and spontaneously. He sought out opportunities to encourage people — from writing personal notes and making phone calls to filling out comment cards at restaurants.

He dedicated time each week to pray with his leadership team for the University’s employees individually, using a printout of names and photos as a guide; more than once, he was able to greet a staff member by name, though they’d never met — and remember that name from then on.

He maintained a self-deprecating sense of humor, and had a knack for making others laugh. He loved students and let it show.

“It was common knowledge that Clyde and Anna Belle showed up at nearly every wedding, funeral, play, ball game, recital and musical performance they were invited to,” said Biola chaplain Ron Hafer, who retired this year after 42 years at the University. “Hundreds of students told the story of eating at a local restaurant, then learning from the manager that Clyde had quietly picked up the tab for their meal.”

Cook’s own half-century relationship with Biola began when he arrived as a student in 1953, having turned down athletic scholarships from 13 major schools in order to pursue a life in professional Christian ministry. He earned a bachelor’s degree in Bible in 1957, and days after graduating, married Anna Belle, his wife of more than 50 years. He soon became the school’s athletic director, a position he held while earning his Master of Divinity and Master of Theology degrees from Biola’s seminary, Talbot School of Theology.

After serving as missionaries in the Philippines for four years, the Cooks and their two children, Laura and Craig, returned to Biola once again, where Cook served as director of the missions department for 12 years — regularly leading teams of Biola students on mission trips to different countries around the world. In 1978, Cook accepted the presidency of the missions organization Overseas Crusades — now OC International. Four years later, Biola’s Board of Trustees invited him to be Biola’s seventh president, a position he held for more than a third of his life.

By June 2007, when he stepped down to allow for his successor, Barry H. Corey, to lead Biola into its second century, Cook had come to be known as the “dean of Christian colleges” by colleagues around the country, and had earned the respect of evangelical leaders the world over.

“His influence extended throughout Christian higher education and to the cause of Jesus Christ around the world,” said James C. Dobson, founder of Focus on the Family. “This [world] is a far better place because of the life and Christian witness of Dr. Clyde Cook.”

Even in retirement, Cook did not let up.

In the nine months after he left office, he journeyed to Indonesia, Singapore, Korea and Hong Kong, bringing the gospel with him. He journeyed to cities across the United States, including Houston, Texas, where he preached on the night before his death.

And then came his final journey — the one he’d spent his life preparing for.

In the crowded church the week after his passing, as he delivered his last message — declaring himself to be more alive in that moment than he had ever been — his was the voice of a man who had been sure of what he hoped for; he was certain of what he had not seen.

Biola University

Biola University