This year marks John Calvin’s quincentenary — the 500th anniversary of the famous theologian’s birth — and his impact on Christian thought and biblical interpretation has never been more strongly felt.

In early 2009, Time magazine named “The New Calvinism” the third most important idea “changing the world right now.” A few months earlier, Collin Hansen published the book Young, Restless, Reformed: A Journalist’s Journey with the New Calvinists. In June, popular Christian blogger Justin Taylor reported to Religion News Service that Calvin’s theology is “the hottest, most explosive thing being discussed right now.”

The popular consensus is clear: Calvinism is back and making more headlines than ever. But why? What were Calvin’s ideas and contributions that, 500 years later, are still having an impact?

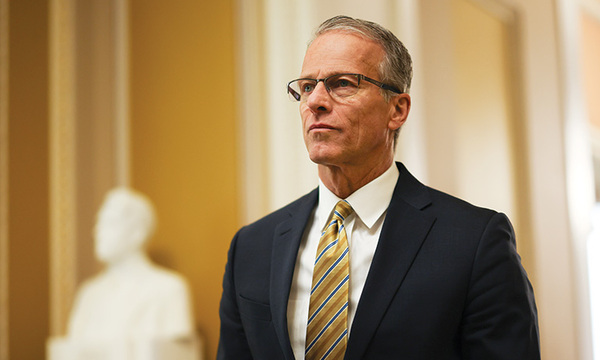

Essentially, what Calvin offered the church was a systematized Protestant theology thoroughly grounded in the Bible, said Robert Price, assistant professor of theology at Biola’s Talbot School of Theology.

“The bottom line for Calvin is his concern for the Bible,” said Price, who is teaching a class on Calvin at Biola this semester.

“Lots of people look at the Bible and have seen in it stories about history and things about the future, things about heaven, things about life — just kind of this wild smorgasbord of ideas — without realizing that it all works together and has a point.”

Calvin’s overarching goal, said Price, was to communicate this “point” so that Christians could get more out of Bible study.

A second-generation reformer, Calvin was building on the larger project of the Reformation - to refocus the church around the Bible and to clear away some of the things that had obscured the biblical witness.

In the 16th century, the Bible was increasingly available to laypeople in their own language, and Calvin — a trained lawyer out of the Renaissance humanist tradition — saw the need to offer people a helpful “study guide” of sorts to better understand and interpret the Bible. Calvin, like other Reformers, did not think it was a good idea to just leave Christians alone in their rooms with their Bible to interpret it however they wished. Rather, he believed that guidance and instruction were necessary.

The result was perhaps his most important single contribution to church history, Institutes of the Christian Religion - a work meant to clue readers in to the themes, patterns and important points that should be gleaned from Bible study. His prioritization of and confidence in Scripture as the final authority (sola scriptura) is one of the “genius legacies” of Calvin, said Price.

“He didn’t see his theology as superseding Scripture; it was supposed to be a tool to help direct you through Scripture,” Price said. “Calvin definitely belongs first and foremost to the ‘What’s the Bible got to say?’ section.”

For Fred Sanders, a professor in Biola’s Torrey Honors Institute, one of the best things about Calvin — and indeed, a reason why he is still so popular today — is that he wrote his theology in a living, dynamic voice that engages the reader and tries to bring about change in the person’s life and thought.

“Most systematic theology is written like a handbook, but with Calvin you have this experience of mental discipleship,” said Sanders, who teaches The Institutes and has read it five times.

Though he’s not a Calvinist and considers himself a theologian in the Wesleyan tradition, Sanders has great respect for Calvin.

“He was just a good, critical reader of Scripture. He was a ‘doctor of the church’ who got the Bible, found patterns within it and began teaching it.”

But what would Calvin think of the contemporary incarnation of the so-called “new Calvinism?”

On one hand, said Price, Calvin would probably be wary of the sort of restorationist impulse that is sometimes seen in Reformed circles, where historical Reformed theology — particularly as it develops in the 17th century — is the be-all and end-all of Christian theology.

“I’m all for drawing on the resources of Christian tradition as an essential component to reviving a church today,” said Price, who is theologically Reformed. “But I don’t think Calvin would be happy about a too-exclusive emphasis on the theology of the past.”

On the other hand, Calvin would probably be pleased that the type of Calvinist resurgence we are seeing today is almost exclusively evangelical and committed to the fidelity of Scripture, noted Sanders.

“Calvinists believe what they do because they believe that’s what the Bible teaches, not because Calvin said so,” he said. “All of them would say that Scripture teaches it, and Calvin is a good guide for them.”

Ultimately, this is the sort of legacy that Calvin - a man who made sure he was buried in an unmarked grave - would have wanted. His work was never about John Calvin, he would say. It was always about Jesus Christ. And it was always about the Bible.

Biola University

Biola University