In what I take to be the kindness of God, I recently enjoyed with my students a rich discovery in an unplanned connection between our Scripture reading at the front end of class and our discussion of As You Like It. In our weeks together studying Shakespeare’s comedies we are reading Colossians from the Geneva Bible, the first mass-published English translation of the Scriptures and the one that Shakespeare likely had in his home.

Our reading from Colossians 2:9-15 reminded us that we who are in Christ Jesus have been filled in him, circumcised in his circumcision, buried with him, raised with him and made alive together with him. Our reading detailed what Paul just a bit later says more succinctly: Your life is hid with Christ in God.

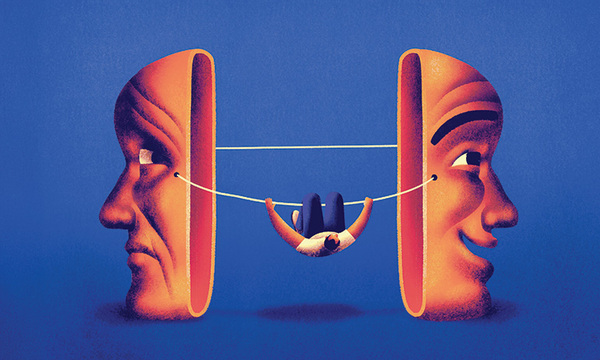

Then we proceeded to our academic task, to discuss the masks that characters take on in Shakespeare’s plays and the relationship between playing a role and being one’s self. As Shakespeare’s Jacques famously holds forth:

All the world’s a stage

And all the men and women are merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances

And one man in his time plays many parts.

It’s not original to Shakespeare, this idea that all the world’s a stage. The concept of the theatrum mundi — the theater of the world in which the human drama plays out before a divine audience — is as antique as the Ancients. But through Shakespeare the notion makes its way into English literature. He keeps reminding his audience that the play world is an analogy for the real world, one in which people are always wearing masks. To be a person is to be an actor.

My class eventually found this notion unsettling. Mere acting so quickly becomes hypocrisy, so readily facilitates an empty self. Are we always putting on masks before others, effectively role-playing at the cost of stable selves? How can we know who we are at core if we simply move from room to room, relationship to relationship, job to job, playing our part? If we are what we do, who are we apart from what we do?

And the answer came straight from Colossians. Our identity is not simply the sum of every part we play. Our very life takes place in the life of Christ. This disrupts the need to know who I am at core and relocates my attention to Christ in me.

A 16th century catechism, the Heidelberg, identifies a radically relocated identity as the first and sole comfort for the Christian, asking its first question: Christian, what is your only comfort in life and in death? And the answer, borrowing Paul’s words to the Ephesian church: That I am not my own, but belong — body and soul, in life and in death — to my faithful Savior Jesus Christ.

The comfort of the gospel is that though I would be lost in myself I find my self in Christ. We pray to God as Father only because we have been included in the life of his Son. We are no longer aliens and strangers to our Creator because we have been brought near in the fellowship of his Spirit. We are no longer dead in our sins — in the many and various ways we act as and become selves opposed to our created nature — because Christ in his life, death and resurrection has triumphed over sin and death.

I am not my own, but Christ’s. So there is more good comfort: By including us in his life, Christ plays out his life in ours. Gerard Manley Hopkins captures this richness in his poem “As Kingfishers Catch Fire.” After a first stanza capturing the richness of being that creatures possess by doing the particular thing they do, he considers the unique situation of the human creature:

I say more: the just man justices;

Keeps grace: that keeps all his goings graces;

Acts in God’s eye what in God’s eye he is—

Christ—for Christ plays in ten thousand places,

Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his

To the Father through the features of men’s faces.

God, both true author and true spectator of this world’s stage, sees Christ in us. Christ has given us a new role to play — his very life in the world. May we gladly and humbly enter into this great drama.

Biola University

Biola University