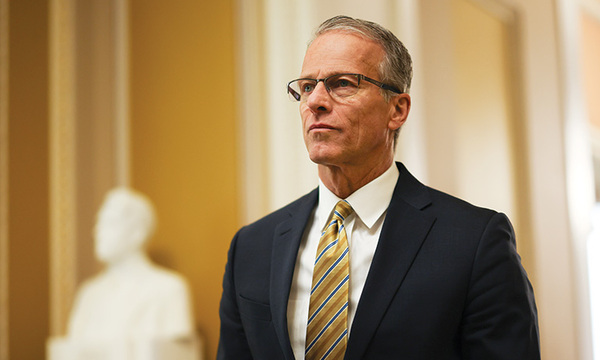

In the growing movement known as intelligent design, Stephen Meyer is an emerging figurehead. A young, Cambridge-educated philosopher of science, Meyer is director of the Center for Science and Culture at the Discovery Institute — intelligent design’s primary intellectual and scientific headquarters. He’s also author of Signature in the Cell, a provocative new book that offers the first comprehensive DNA-based argument for intelligent design.

On May 14, Meyer gave a lecture at an event hosted by Biola's Christian apologetics program in Chase Gymnasium, where he made his case that the origin of the information needed to create the first cell must have came from an intelligent designer. Biola Magazine sat down with Meyer while he was at Biola and asked him to elaborate on evolution, the scientific merit of the theory of intelligent design and the uncanny similarities between DNA and computer programming.

When it comes to evolution, what type of evolution do you agree with and what type do you deny?

Well, evolution can have several different meanings. It can mean change over time, or it can mean that all organisms share a common ancestor such that the history of life looks like the great branching tree that Darwin used to depict the history of life. Or it can mean that a purely undirected process — namely natural selection acting on random mutations — has produced all the change that has occurred over time. I think small-scale microevolution is certainly a real process. I’m skeptical about the second meaning of evolution — the idea of universal common descent, that all organisms share a common ancestry. I think the fossil record rather shows that the major groups of organisms originated separately from one another. But that’s not what the theory of intelligent design (ID for short) is mainly challenging. We’re challenging the third meaning of evolution, and that’s where we kind of go to the mat. We do not think that a purely undirected mechanism has produced every appearance of design that we see in nature or in biology. So I’m skeptical of that third meaning, sometimes called macroevolution, where we’re really talking about the mechanism of natural selection and mutation. My book, Signature in the Cell, is actually about an even prior question, which is the origin of the first life, sometimes explained by a theory called chemical evolution. That’s the main target of my own research. I’m showing that that doesn’t work at all. For example, I don’t think there’s any evolutionary account for how you get from molecules to cells.

How old do you think the universe is?

I tend to think it’s old. About 4.6 billion years. I tend to think humans are pretty recent, however.

Do you affirm the Big Bang?

I think the Big Bang is a good theory, and I think it actually has theistic implications. It establishes, along with the field equations of general relativity, that there was a singular beginning to the universe, in which both time and space begin.

One of the big unanswered questions you see in the theory of evolution concerns the origin of the information needed to build the first living thing. How do the Darwinists answer that question?

Many people don’t realize it, but Darwin did not solve, or even attempt to solve, the question of the origin of the first life. He was trying to explain how you got new forms of life from simpler forms. In the 19th century, this was a question very few scientists addressed. The standard theory in the 20th century was proposed by a Russian scientist named Alexander Oparin who envisioned a complex series of chemical reactions that gradually increased the complexity of the chemistry involved, eventually producing life as we know it. That was the standard theory, but it started to unravel in 1953 with the discovery of the structure of DNA and its information-bearing properties, and with everything we were learning about proteins and what I call the “information processing centers” in the cell, the way the proteins were processing the information on the DNA. Oparin tried to adjust his theory to account for these new discoveries, but by the mid-60s it was pretty much a spent force. Ever since, people have been trying to come up with something to replace it, and there really has been nothing that has been satisfactory. That’s one of the things the book does. It surveys the various attempts and shows that in each case, the theories have a common problem: They can’t explain the origin of the information in DNA and RNA. There are other problems as well, but that’s the main problem.

What would be your main argument for the evidence of intelligent design in the cell?

Well, the main argument is fairly straightforward. We now know that what runs the show in biology is what we call digital information or digital code. This was first discovered by [James] Watson and [Francis] Crick. In 1957, Crick had an insight which he called “The Sequence Hypothesis,” and it was the idea that along the spine of the DNA molecule there were four chemicals that functioned just like alphabetic characters in a written language or digital characters in a machine code. The DNA molecule is literally encoding information into alphabetic or digital form. And that’s a hugely significant discovery, because what we know from experience is that information always comes from an intelligence, whether we’re talking about hieroglyphic inscription or a paragraph in a book or a headline in a newspaper. If we trace information back to its source, we always come to a mind, not a material process. So the discovery that DNA codes information in a digital form points decisively back to a prior intelligence. That’s the main argument of the book.

Your book talks a lot about information and you find parallels between a software program and our DNA. Do you think the ideas in your book about programming and programmers would even have been conceivable to readers trying to understand intelligent design a generation ago?

That’s a great question. I think the digital revolution in computing has made it much easier to understand what’s happening in biology. We know from experience that not only software but the information processing system and design strategies that software engineers use to process and store and utilize information are not only being used in digital computing but they’re being used in the cell. It’s the same basic design logic, but it’s executed with an 8.0, 9.0, 10.0 efficiency. It’s an elegance that far surpasses our own. It’s a new day in biology. It’s a digital revolution. We have digital nanotechnology running the show inside cells. It’s exquisitely executed and suggests a preeminent mind.

What is “specified complexity” and how does it play into your argument?

It just refers to strings of characters that need to be arranged in a very precise way in order to perform a function. If they are arranged in a precise way such that they perform a function, they are not just complex but specified in its complexity. The arrangement is specified to perform a function.

I’ve heard the argument that the likelihood of specific genetic instructions to build a protein falling into place would be like a bunch of Scrabble letters falling on a table and spelling out a few lines of Hamlet. But couldn’t you just say that the chances of winning the lottery are also very slim, but someone usually does get lucky? What if the universe forming was just the proverbial “lottery winning”?

But there are some lotteries where the odds of winning are so small that no one will win. And that’s the situation of trying to build new proteins or genes from random arrangements of the subunits of those molecules. The amount of information required is so vast that the odds of it ever happening by chance are miniscule. I make the calculations in the book. There’s a point at which chance hypotheses are no longer credible, and we’ve long since gone past that point when we’re talking about the origin of the information necessary for life.

Some have criticized ID as being primarily a negative enterprise, denying things but not really offering scientifically convincing alternative. In a recent Christianity Today article, Karl Giberson said that ID advocates should “stop trying to prove that Darwin caused the Holocaust or that evolution is ruining Western civilization. … Instead, roll up your sleeves and get to work on the big idea. Develop it to the point where it starts spinning off into new insights into nature so that we know more because of your work.” How do you respond to this?

Well, we are doing this. What Giberson isn’t doing is reading our work. In the back of Signature in the Cell I lay out the research program of ID and an appendix that develops 10 key predictions that the theory makes. There’s a new journal called BIO-Complexity that is investigating the heuristic fruitfulness of intelligent design. It’s testing the theory, looking at papers that generate predictions based on the theory, publishing papers that are developing new lines of research based on the theory.

To the point that it’s mainly a negative enterprise — that is completely incorrect. ID is proposing an alternative explanation of life. It’s not just criticizing Darwin or criticizing chemical evolution; it’s proposing a contrary explanation and in light of that explanation, developing a number of important hypotheses that can be tested in a laboratory.

Do you ever tire of having to defend the scientific legitimacy of ID?

The thing that is most frustrating is that people seem to feel comfortable making comments about our work without even knowing what it is. The characterizations or criticisms of ID often bear no resemblance to what is actually being done, said, researched or written. There have been any number of reviews of my book that were clearly written by people who hadn’t even read it. ID is an idea that some people think they can attack without impunity, because it is so disreputable.

John Walton, an Old Testament professor at Wheaton College, said this about ID in his recent book on Genesis: “Science is not capable of exploring a designer or his purposes. It could theoretically investigate design but has chosen not to by the parameters it has set for itself. … Therefore, while alleged irreducible complexities and mathematical equations and probabilities can serve as a critique for the reigning paradigm, empirical science would not be able to embrace Intelligent Design because science has placed an intelligent designer outside of its parameters as subject to neither empirical verification nor falsification.” Do you agree with this?

I think it’s strange that a biblical scholar would weigh in on the definition of science. His definition of science doesn’t work. Science often infers things that can’t be seen based on things that can be seen. Darwinism does that. In physics, we talk about quarks and all sorts of elementary particles. We don’t see those. They’re inferred by things we can see. I don’t think his concept of science comports with the experience of scientists. Direct verification is not a standard that separates science from any other discipline. It’s also a odd thing for a biblical scholar to say, because the biblical witness is that from the things that are made, St. Paul says, the attributes of God are clearly manifest, and one of his attributes is intelligence. So why should it be surprising that if we look at things carefully and reason about their origins, that we would come to the conclusion that a designing intelligence had indeed played a role in their origin?

It seems like the idea or inference of anything supernatural scares scientists away. Do you agree?

Well, all we are inferring is intelligence. Whether it is supernatural or natural is a matter for further deliberation. I don’t even like the term “supernatural.” I think the better philosophical distinction is between transcendent and immanent. Are we talking about an intelligence within the cosmos or an intelligence that is in some way beyond it? And that’s a theological distinction. I think it is possible to reason about that, and whether you call it a philosophical deliberation or not, it doesn’t really matter. All the theory of intelligent design is doing is establishing that intelligence was responsible for certain features of life. We recognize intelligence all the time, and we have scientific methods for it. If you’re an archaeologist and you’re looking at the Rosetta Stone, are you duty-bound to continue looking for naturalistic explanations even though you know full well that wind and erosion and everything else you can imagine is not capable of making those inscriptions? No, you’re not. You really ought to conclude the obvious, which is that a scribe was involved. There was an intelligence behind it.

But then, doesn’t the inquiry become one of history rather than science?

It’s historical science. That’s what my Ph.D. dissertation was about and it’s part of what I defend in the book. That’s what Darwin was doing. He was doing an historical science — attempting to infer the causes of an event in the remote past. There’s a scientific method by which you can do that which addresses questions of past causation. Sciences such as archeology, geology, paleontology, cosmology are concerned with those kinds of questions. Intelligent design is using the same sort of scientific methods that these sciences are using.

People are hung up on how to classify intelligent design. But how you classify a theory is not all that important. Whether it’s science, religion, philosophy, history — why can’t it be all four? I think Darwinian biology is certainly science, certainly history, and certainly has larger metaphysical and philosophical implications. Nature and the world do not present us with tidy categorical distinctions.

Why do you think scientists are so adamant that the admission of a metaphysical, teleological explanation of the universe would undermine the practice of science? If such a thing could be shown to be provable, or even just probable, shouldn’t it excite the scientific mind? I think of a scientist as being in awe of the wonder of the world.

It’s a very astute question. The origin of modern science was spawned by scientists who had precisely this sort of awe. They were in the main Christians who believed that science was possible because nature was intelligible. It could be understood and comprehended by rational minds such as ourselves because it had been designed by a rational mind in the first place — that God had put into nature order and design and discernable pattern. That’s what made it possible to do the hard work of looking at things and then eventually discerning that there was a pattern. Kepler said that scientists have the high calling of “thinking God’s thoughts after him.” Design was part of the foundational assumption of modern science. Scientists assumed that nature was designed, and that’s why they could do science. Now roll the clock forward 300 years and you have scientists saying that if we allow a design hypothesis in any realm of science, even if we’re talking about something like the origin of the first life, that we are undermining the very foundation of science. In fact, we’re getting back to the very foundation of science and to that awe and wonder that was the inspiration for the whole enterprise.

There are many evangelical Christian scientists who disagree with you — even people familiar with genetics and DNA, such as Francis Collins. On what points do you agree with someone like Collins, and at what points do you disagree?

There are a number of points on which I agree with Collins. He says that he’s against intelligent design, but he actually makes arguments for intelligent design in The Language of God. He says intelligent design is the best explanation for the fine-tuning of the laws of physics and chemistry. He also argues that the moral sense of humans cannot be explained by undirected processes. Collins denounces ID as a “God of the gaps” argument or an argument from ignorance, but yet he’s making arguments for intelligent design based on physics. I think he sees theistic implications from the Big Bang, and I agree with that. Where we differ is that he wants to hold out for a materialistic explanation of the origin of life, and I think he thinks that Darwinian evolution is sufficient to account for new forms of life. One of the things I’ve been asking Collins to clarify, as a theistic evolutionist, is what he means by evolution. Which of those three meanings of evolution does he affirm? Change over time, common ancestry? I know he affirms those. But what about the third meaning? The idea that the evolutionary process is purely blind and unguided. I had a chance to ask him personally: Is the evolutionary process directed or undirected? He paused, and responded, “It could be directed.” If he says it is directed, he’s got a problem because he’s breaking with the dominant materialist view of the scientific establishment. If he says it’s undirected, then he’s going to lose his influence with the evangelical Christian church, which he’s desperately trying to influence. If he says that evolution is essentially undirected, that’s not consistent with the biblical view he espouses. Instead, it’s a form a deism in which nature is doing all the work and God is either absent or just watching from the mezzanine.

What is the most compelling argument that you’ve come across from your opponents? What do you think is the hardest thing to overcome from your position?

I think one of the strongest challenges to intelligent design has always been the observation of things in nature that are not going well or don’t look like they were intelligently designed. In the book I have a section on pathogens and virulents. There have been these horrific diseases in the history of life — like the plague. People ask me, “Do you really want to say the plague was intelligently designed by God?” And as Christian and a design theorist, of course I don’t want to say that. So there are then three options to respond to this, sometimes called the problem of natural evil. One option is that there really is no evil, natural or otherwise; it’s just that you’ve got random mutations producing things that we like and things that we don’t like. That was essentially the Darwinian view. He was going to let God off the hook by saying essentially that God had nothing to do with it. He didn’t want to make God responsible for evil, so he made God responsible for nothing at all. The other view is that it looks like you’ve got design, but it looks like you’ve got a good designer and a bad designer at the same time. A third view — which I think is more in line with a Christian view of design — is that the world is simply evidence of a good design gone bad.

What does ID have to do or prove to get more of the mainstream scientific community on board with it?

I think it needs to continue doing what it’s been doing, making the case and focusing on the evidence, and then challenging the rules of science that prevents scientists from considering ID as an explanation. I think this is the main impediment.

What do you hope for the future of the ID movement?

We’re trying to grow it. We want to see more scientists come in to it. And I think it is incumbent upon us to develop a robust research program of questions that flow from an ID perspective. If ID is correct, life ought to look different than if it were the result of random processes of mutation and selection. One of the key predictions that illustrates how it ought to look different is the prediction about junk DNA. We’ve been saying since the early ’90s that the non-protein-coding regions of the genome — which the Darwinists said to be junk — are not going to be shown to be junk. If ID is true, it makes no sense for a designing intelligence to design an information system in which 97 percent of it is doing nothing. We’ve predicted that yes, you ought to see some mutational decay and some errors over time, but the signal should not be dwarfed by the noise. What we’ve been seeing in the last 10 years is that that prediction has been substantially, overwhelmingly confirmed. That’s an example of how the ID perspective is anticipating discoveries in science, suggesting testable predictions, and I think that’s the future of ID.

Biola University

Biola University