Jump to:

Knowing the Market

Building and Maintaining Trusted Relationships

Being Smart about the Film's Budget

Getting Films Sold to Distributors

Negotiating a Good Distribution Deal

Avoiding Expensive Pitfalls

Independent film producers make money by:

- Knowing their market

- Building and maintaining trusted relationships with investors

- Being smart about the budget on the front end of production

- Getting their films sold to distributors

- Negotiating a good back-end deal

- Knowing and avoiding expensive pitfalls

If you can execute on each of those, you'll make money as an independent film producer. Easy, right?

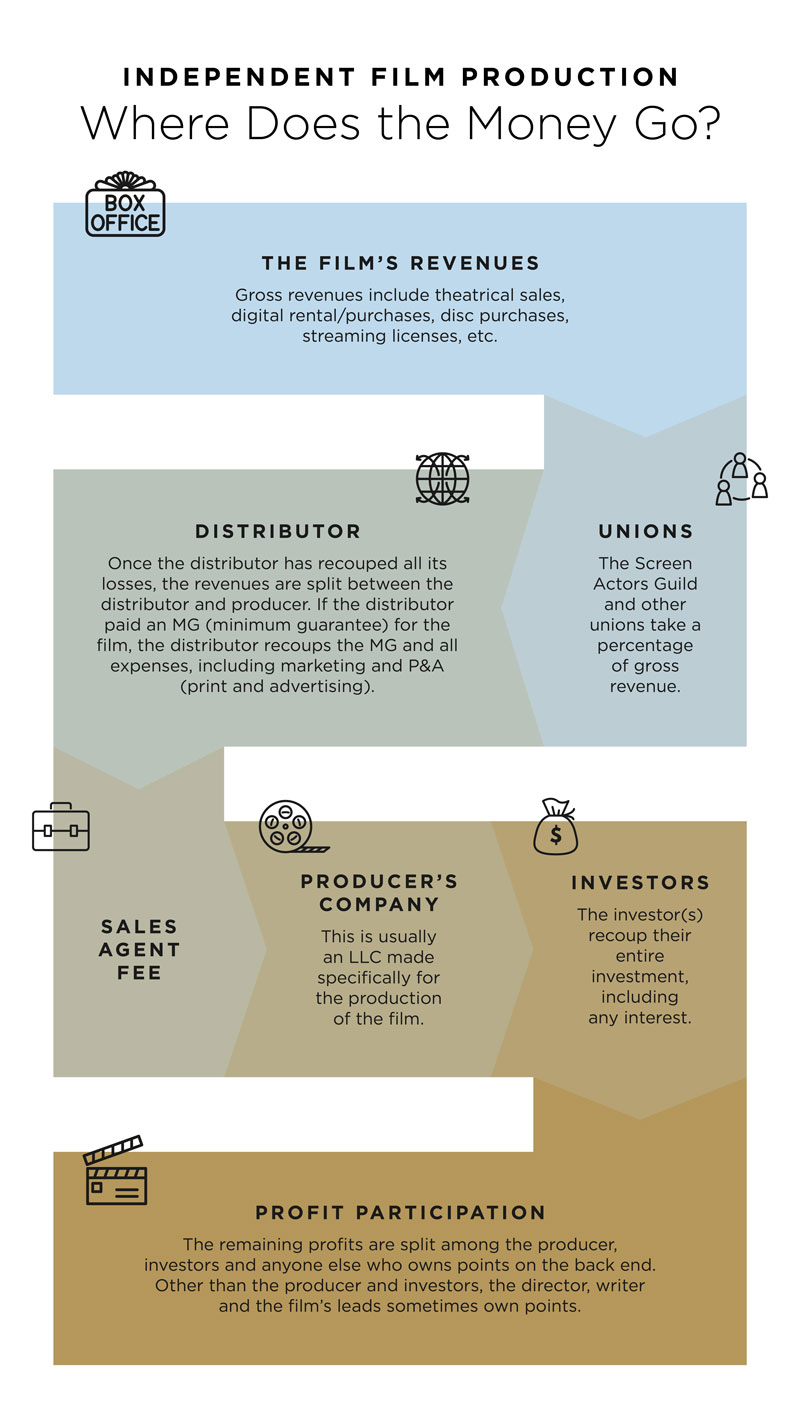

Film producers earn money in several different ways while the film is being made and after it's been sold. The compensation structure looks very different for both stages:

Front end: This refers to before, during and after the film's production, or pre production, production and post production. When a film is referred to as high or low budget, it's the production budget that's being discussed. The producer takes a salary from the budget like other people working on the movie (actors, director, etc.). This is a razor that cuts both ways: an independent producer can choose her own salary, but if something goes sideways during production and there's no budget left to cover it, the producer's salary is likely to become a contingency fund. An inexperienced film producer can end up using his salary to ensure the movie gets made and take home nothing. Some producers opt to pay themselves last. There isn't an accepted rule for what percentage of the budget a producer might take as salary.

Distributor deal: When the producer sells the movie to a distributor (a movie studio or a streamer), the producer negotiates the split of revenue that the film generates when it’s released into the market. We talk more about the details of how this works in the section “Negotiating a Good Distribution Deal” later in this article.

Back end: “Back end points” is film industry terminology for percentage of ownership or profit participation. A point is worth one percent of revenue. Once the investor has recouped his or her investment in having the film made, the revenue the film generates goes into this profit participation pool and is split according to any back end deals that have been made with actors, investors or other parties Here again, the movie producer has total control over negotiating the back end points. We'll discuss points in more detail later.

Knowing the Market

Before the cameras, before scripts or pre-production or even investors, the movie producer needs an idea for what this film is going to be. Whatever story is going to be told needs to be compelling enough to fit somewhere within a very competitive landscape. Once the movie is made, it's going to be competing with Spider-Man, which is playing in the theater just across the hall. Or against Ted Lasso or The Office on streaming services, or whatever notification is pinging on someone's phone. There's an ever-increasing number of ways for people to spend their time and attention with still only 24 hours in each day.

Disney, for example, is not in the game to just make princess movies. Disney is in the game to sell merchandise all year long, to sell the idea in video games and sell tickets to amusement parks. Films are long-form advertising to get consumers to buy products.

Making a movie just because it's a good story or because the producer is passionate about the idea is fine, as long as the producer is also prepared to self-fund the project or spend years repaying the investor for a film that made no money. A first-time film producer who fails probably won't have the chance to make another movie again. Once a producer has failed to generate return on the initial investment, nobody will want to risk investing in that producer's projects. Passion projects without any market assessment are the opposite of how a producer makes money.

Many film schools unfortunately fail to teach the commerce side of the business and only teach the art. Artistic vision and technical mastery are important, as long as you have an infinite pool of resources to just make art.

This is not to say passion has no place in producing films, but a successful producer pairs passion with an acute awareness of what's going on in the world and what's going on inside the entertainment industry. The producer needs to identify what specific demographics the film is going to appeal to, and why the film will compel those audiences to spend their money and attention to watch. Pitches will need to be crafted for investors, and investors want data, numbers and facts when making decisions about whether to invest.

Building and Maintaining Trusted Relationships

Investor Relationships

Speaking of investors, this is one of the key trusted relationships an independent film producer must cultivate. Often, independent producers work with private equity financiers or private investors to fund their film production. Even a shoestring budget of $1 million to make a feature film is more money than most producers have when getting started, and outside funding is typically necessary. The investor will fund the film production budget. He or she is often listed in the credits as an executive producer, and may also weigh in on financial and some creative decisions. If there are multiple offers from distributors to buy the movie, the investor is frequently involved in deciding which offer to take.

In return for the investment, the producer is responsible for paying back the investment in full. Sometimes an investor will look for interest on the investment, which is something the producer would negotiate. As mentioned earlier, a producer whose film doesn't make money is going to have a very hard time securing future funding, because the investment was based on trust in the producer's ability to read the market and produce a movie that makes money.

To summarize: Movie producers who demonstrate an ability to make money also earn the trust of their investors. Investors like making money and are likely to invest in future projects with producers whose films are successful.

Trusted Relationships with Talent and Crew

Due to reasons ranging from carelessness or incompetence to outright maliciousness, almost any one person on a film production crew has the opportunity to cause expensive delays in production. For a producer who's paying everyone's salaries with an investor's money (which the producer is on the hook to repay), that reality is a bit unnerving. There are only so many days for shooting and a limited amount of money to pay for what needs to be done. If the people on the team can't execute, the producer will need to start cutting from other budgets or shuffling money around, and the film quality gets compromised.

This is why many producers often work with the same people for every project: confidence in the ability to deliver. They hire people with whom they have existing relationships or who come highly recommended by someone they know. (This is also why the friendships made in film school are so important, because film school allows students to develop a trusted network with many areas of expertise.) This practice of working together repeatedly is more visibly seen among actors and directors because of their higher profiles, but it's common among movie producers and production crews as well.

Experienced Entertainment Attorney

So much of a producer's job is reading and negotiating contracts. Contracts with investors, talent, crew, agents, distributors, and the list goes on. There are months of paperwork and contracts in pre-production before producers start filming, and nobody sees any money on the other side until a contract with a distributor is negotiated and the film is sold. The best friend a successful producer can have is a sharp entertainment attorney. A good producer needs to be adept at understanding and negotiating contracts, but even so, that's no substitute for a law degree.

Being Smart about the Film's Budget

For independent films that are made without the big budgets of major studios, keeping costs low—without sacrificing quality—is essential. This is where a producer needs to be extremely creative. Every film is broken down into production days, or days of filming. For indie films the cost of production will ultimately be the bulk of expenses, (considering that indie films aren’t typically VFX-heavy movies).

If the producer spends too much money on cast, crew and locations, the producer will have fewer days to shoot the movie. This means the producer needs to shoot more script pages per day in order to finish the film. This can hurt the movie because there will be fewer takes per shot, which can lower the quality of the film.

Conversely, if the producer spends less on cast, crew and locations, there will be more days to shoot the movie. However, with less money allotted for wages, the producer may end up with a less-experienced cast and crew, and potentially fewer crew members overall. An inexperienced cast may take longer to get the scenes correct, which means having to shoot more takes than anticipated. A smaller or inexperienced crew may take longer during production to set up every shot. This will bite into your time. So even with more days to shoot and fewer pages to shoot per day, the result still might end up being a lower-quality movie. So having more days to shoot doesn't necessarily translate to having a better movie.

There isn’t one singular formula for how to produce a high-quality film on a tight budget. It hinges on the producer’s ability to strike the right balance between cost and time for each production. Relationships in which the producer has already invested and has a few favors to call in are key to getting this balance right.

Getting Films Sold to Distributors

When an indie film is finally made, the producer still needs to sell it to a distributor so it can start generating revenue to repay the investor and make money. Distributors are streamers like Amazon Prime or Netflix and movie studios like Warner Bros., Paramount, A24 or Neon. A producer can't go directly to a distributor, though. Distributors only talk to sales agents, unless the producer happens to have a personal relationship with the president of a studio, which is obviously very rare.

Step 1: Get a sales agent. To get an independent film sold, the producer needs to get a sales agent through a company like CAA, WME or Gersh. These are a few of the big agencies that represent writers, directors, athletes and other talent. They also have divisions that do nothing but finance, and that's where the sales agents work.

Sales agents won't pick up just any project. If the movie doesn't have any known stars or maybe just isn't very good, or the film producer doesn't have any track record, it may not be able to get a sales agent. At that point, the movie sits on the shelf, collecting dust. If the film is picked up by an agent, the producer signs a contract with the agent, and the agency usually takes 10% of revenue.

Step 2: Get the film screened. For that fee, the agency schedules a screening with the people in acquisitions at the various distributors. Prior to Covid-19, this happened at the agency's private movie theaters or a theater rented for the purpose of the screening. At the time this article was published, it's a virtual screening. All the executives gather to watch the film together at a scheduled time, which is intentional.

Here's why: let's say the producer has a buddy at a studio who begs to see the movie before the screening. He watches it and knows it's good but doesn't want to buy it at the price the producer wants. So he goes around town telling everyone he's seen it and it's not a good film. When it finally gets officially screened, people don't show up or send their interns who only care about Marvel movies, and nobody takes it seriously. Once everyone else has passed, the producer has to go crawling back to the "buddy" who offers a terrible deal to buy the film. The film industry can be a bit cutthroat. Smart producers don't share their films in this way.

Step 3: Get offers (hopefully). Once the studios have screened the movie, the sales agent starts following up with the acquisitions people at studios. Most of those people will pass. But if the producer was smart about reading the market and making a movie with commercial appeal, there may be multiple offers. For independent films, getting into a film festival like Cannes or TIFF can make the film more desirable, but that's not a guarantee. There are stories of indie films that are big hits at film festivals but nobody wants to buy them. That's generally because Sundance audiences care about arthouse films, and executives care about making money. Heartfelt coming-of-age stories, however beautifully crafted, are unlikely to bring in the kind of money Batman will.

Negotiating a Good Distribution Deal

At this point, once there are offers on the table, the agent will set up meetings between the producer and each distributor who's made an offer to discuss terms. And then the fun begins: the deals get pitted against each other to maximize whatever elements the producer wants to prioritize. These negotiations might take weeks or even months before the deal is done. There are a few components to these deals:

Minimum guarantee, or MG: A minimum guarantee is like a down payment or an advance on the film. The distributor pays the filmmaker a set amount up front. This could be in the hundreds of thousands, which wouldn't be bad for an independent film, or it could be significantly more. Most offers don’t come with a minimum guarantee. If the distributor knows the producer is desperate, if the movie isn't good enough or if the movie doesn’t have commercial appeal, there might be no minimum guarantee.

The distributor will recoup the MG before starting to share profit, so this may be the only money the producer will see for a while (hopefully not ever, though that's possible, too). A higher MG usually means a lower share of profit, and vice versa. Let's say it's for a new producer and the MG is $250,000.Profit: Once the movie is released to the box office, rentals or streaming, the distributor is going to take the revenue that comes in to recoup the $250,000 MG. After that, the revenue that comes in gets divided. With a lower MG, the producer would negotiate for a higher percentage of revenue: 40% stays with the distributor and 60% goes to the producer. If the MG was higher, this might be reversed, and the distributor keeps 70% and passes 30% to the producer. Either way, the revenue that goes to the producer is what funds the back end points (after the initial investment has been repaid).

Term: The producer should negotiate for the length of the term (5 years, 10 years, 15 years). When a distributor buys a film, they are licensing the film for a certain amount of time. Once the term is done, the rights to distribute the film revert back to the producer.

Territories: Distributors often take "territories" when they are licensing (buying) a film. For example, a domestic distributor may ask for the rights to distribute in North America (United States and Canada). A foreign distributor might ask for distribution rights for all territories outside of North America. A big distributor (like Netflix) may ask for worldwide rights, which gives them the ability to sell to any territory in the world. If a foreign distributor only wants certain territories (for example, only South America, Australia and the UK), the remaining pieces may be harder to sell.

Let's say the film that cost $1 million to produce receives a minimum guarantee and sells for $250,000. The minimum guarantee of $250,000 may need to go straight to paying the investor, depending on the type of deal the producer has made with the investor. If the investment was $1 million and the MG of $250,000 goes to the investor, a remaining balance of $750,000 is still owed (assuming the investor didn't require any interest).

The distributor will keep all revenue generated by the movie until it recoups its $250,000 minimum guarantee and its marketing costs. After that, as the film continues to generate money, the distributor will take its cut of 40%. Of the 60% that theoretically goes to the producer, other parties take a cut first:

Sales agent takes 10%

- Unions:

Screen Actors Guild (SAG, the actor union): SAG’s cut changes from year to year and varies based on the budget tier of the film. In 2019, for the modified low-budget tier (films under $750,000) was 3% of gross revenue, not just the producer’s 60%.

- International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE, the crew’s union)

Note: It’s not uncommon for independent filmmakers to hire non-union crew. Union crew is often too expensive and won’t make or break the success of the film the way a non-SAG actor would.

Investor: The first $750,000 is paid to the investor for the initial investment of the film production budget.

Once the investor is fully repaid, the 60% starts funding profit participation. The investor and the producer will have negotiated how many points they each get, or how they’ll share the profit. The producer may have given some points in negotiations, often with talent. If an actor's salary is a little lower, back end points can be offered as part of the actor's compensation.

As long as the movie is generating money in rentals or streaming, profit continues to be shared according to whatever deal has been structured.

Avoiding Expensive Pitfalls

There are any number of ways to lose money while making movies. Here are a few of the most efficient ways independent film producers can end up in the red.

Paying interest to the investor: If there is interest on the investment (something that is agreed to at the beginning), then the investment and its interest is paid in full before moving into profit participation. It's not that it's unreasonable for an investor to want to mitigate some risk by charging interest, especially for a producer who has no track record. But interest does make it that much harder for a producer to make money.

Failing to get contracts: In pre-production, producers spend a lot of money with attorneys to get contracts drafted for every person who's hired. A distributor won't buy a film that involved people who were working without contracts because it presents a potential liability for the distributor. If, for example, someone's face appears in a film and that person hasn't granted permission in a contract for that to happen, the person can sue the distributor (which happened with the Netflix docuseries Tiger King). Film school doesn't usually teach students how to read or negotiate a contract, but these skills couldn't be more necessary for independent filmmakers.

Hiring someone just based on a resume: It's been said once but deserves to be repeated. A good producer doesn't take chances with untested production personnel. With tight schedules and money at stake, the producer needs to trust everyone on the team to do their own jobs. That trust comes from prior experience working together or personal recommendations from the producer's trusted relationships. While not the norm, there are enough horror stories about producers who raised money for a film and entrusted it to someone else, and that person skipped town with the money. Trust is everything.

Getting hustled by a distributor: Distributors work to maximize profits for themselves. This doesn't make them bad; it makes them businesses. If an inexperienced producer fresh out of film school sells a film to a guy working at a distributor who's been doing his job for 20 years, the young producer isn't likely to get a great deal. When a distributor makes an offer (and they will be the first to make an offer), they'll start with their lowest number. The terms of the offer will heavily weigh in the distributor’s favor. It's the producer's responsibility to negotiate for the best deal. However, when a producer is new to the game, it's hard to detect what is good or bad. This is why new producers especially need trusted advisors to lean on, including an experienced entertainment attorney, other producers and friends who have been in the game longer.

Not capping the marketing budget: When a distributor buys a movie, one of the items in that contract will be a marketing budget. The distributor will recoup the marketing budget before passing profits to the producer. A savvy producer will put a cap on the marketing budget in the contract, which can otherwise become a black hole into which all profits will disappear. Producers should negotiate the amount that's allocated to the marketing budget.

Getting stuck in post production: A movie has to go to a post production house for editing, adding visual effects and getting it compliant with broadcast standards. A producer can't just cut the film at home on a computer and export it to a distributor. For broadcast, the film has to pass quality control and be brought in line with luminance standard, color standard and decibel standard. Even a low-budget film can run through hundreds of thousands of dollars in a few weeks of post. In the event that the director is inexperienced or indecisive and wants to keep making changes, post production can stretch out over a year and bleed money the whole time.

Take your next step toward becoming a producer. Learn more about our B.A. in Cinema and Media Arts with a concentration in Creative Producing.

This content should be used for informational purposes only. It is not intended to provide legal or financial advice.

Biola University

Biola University