Denis Diderot (1713-84), editor and primary author of the massive—18,000 pages!—and massively influential Encyclopédie, has been called “the pivotal figure of the entire 18th century.” One of the pivotal moments in Diderot’s own career came in his conversion from deism to atheism. And central to this conversion were the implications he drew from Newton’s formulation of the principle of inertia.

Denis Diderot (1713-84), editor and primary author of the massive—18,000 pages!—and massively influential Encyclopédie, has been called “the pivotal figure of the entire 18th century.” One of the pivotal moments in Diderot’s own career came in his conversion from deism to atheism. And central to this conversion were the implications he drew from Newton’s formulation of the principle of inertia.

So what is inertia and how did it shake Diderot’s worldview? Inertia is that inherent conservatism of matter by which things just keep doing what they’re already doing. “An object at rest stays at rest”—no kidding—“and an object in motion stays in motion, until acted upon by an outside force.” We’ve all seen sitting stones keep on sitting. Inertia tells us nothing new there. It’s the claim about staying in motion that’s counterintuitive. Why? Because every moving thing we’ve ever observed has either been slowing down, or it’s had something keeping it going. The wadded piece of paper simply won’t make it to the far side of the room, no matter how hard you throw it. It slows down fast. The flying bird, on the other hand, has to keep flapping its wings to stay in flight.

The problem with our observation of things in motion is that we don’t think of air as exerting a slowing-down force on the objects flying through it. Air brakes. Because of this, we think of rest as having a kind of logical priority over motion. First something is at rest. Then it’s in motion. And it takes effort (force) to start the motion. That’s why thinkers from Aristotle to Descartes had looked out at all the motion around us, especially out in the heavens, and reasoned that ultimately it had to be God who put it all in motion. God is the great Mover of all moving things in the universe, the Giver of Motion.

Newton, as it were, sucks the air out of this reasoning. Without air brakes, without air resistance slowing things down, that is, in a vacuum, that wad of paper will just keep sailing and sailing and sailing. Forever. Newton’s formulation of the principle of inertia means that rest has no logical priority over motion. Both are relative terms. Things don’t necessarily have to be set in motion. If you suspect that matter might be eternal, accounting for eternal matter’s motion is no longer a problem. The principle of inertia suggests that we have no need of the hypothesis of God to explain motion in the universe.

Newton, as it were, sucks the air out of this reasoning. Without air brakes, without air resistance slowing things down, that is, in a vacuum, that wad of paper will just keep sailing and sailing and sailing. Forever. Newton’s formulation of the principle of inertia means that rest has no logical priority over motion. Both are relative terms. Things don’t necessarily have to be set in motion. If you suspect that matter might be eternal, accounting for eternal matter’s motion is no longer a problem. The principle of inertia suggests that we have no need of the hypothesis of God to explain motion in the universe.

Diderot realized, however, that although God was no longer needed to explain cosmic motion, he was needed all the more to explain cosmic mechanism. Newton’s cosmos was a vast machine, its innumerable parts intricately coordinated and tuned to mathematical precision. So even if there might always have been stuff in motion, surely only God could have fashioned a clockwork universe like this.

Abandoning the Aristotle-to-Descartes line of reasoning, Diderot felt that the inference to be drawn from the cosmos was no longer from its motion to God the Giver of Motion, but from its design to God the Designer Almighty. On the strength of this argument from design, the deistic Diderot of 1746 enthused against his atheistic acquaintances: “It is not from the hands of the metaphysicians that atheism has received the weightiest strokes. If this dangerous hypothesis is tottering in our days, it is to experimental physics that such a result is due. It is only in the works of Newton [and others] that people have found satisfactory proofs of the existence of a being of sovereign intelligence.” (Philosophical Thoughts 18)

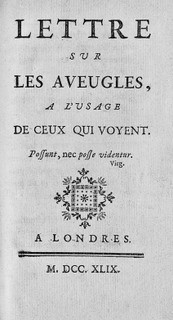

It’s your standard design-proves-Designer deism. What then led our exultant deist to take the plunge into atheism? Another failure of inference. In his Letter on the Blind for the Use of Those Who See of 1749—the very year that Hume began drafting his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion—Diderot frames a dialogue around such apparent failures of design as human blindness. What ought one to infer from these? Not God, according to Diderot. (If, like Diderot, you deny that human sin corrupted the perfect design of the cosmos, then blindness is proof of less-than-perfect design and therefore a less-than-perfect Designer, something other than God.)

The Letter is an extraordinary feat of imaginative description. Through dramatized conversations with two blind men, Diderot explores the way the world appears to the blind and suggests ways in which visual analogies corrupt the reasoning of those who claim to see. The latter of these two men, and the dramatic centerpiece of the Letter, is a fictitious Nicholas Saunderson (1682-1739)—not indeed an atheist in life, but posthumously christened one by an audacious Diderot. The real Saunderson had been blind from early childhood, but his spectacular scientific and mathematical genius got him appointed to Isaac Newton’s old job: the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge. (The same held by Stephen Hawking until 2009.)

The Letter is an extraordinary feat of imaginative description. Through dramatized conversations with two blind men, Diderot explores the way the world appears to the blind and suggests ways in which visual analogies corrupt the reasoning of those who claim to see. The latter of these two men, and the dramatic centerpiece of the Letter, is a fictitious Nicholas Saunderson (1682-1739)—not indeed an atheist in life, but posthumously christened one by an audacious Diderot. The real Saunderson had been blind from early childhood, but his spectacular scientific and mathematical genius got him appointed to Isaac Newton’s old job: the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge. (The same held by Stephen Hawking until 2009.)

“Saunderson” will hear nothing of an intelligent Designer of his own flawed condition, let alone a flawed universe. How then did this less-than-perfect world come into being? “I conjecture,” says “Saunderson” (i.e., Diderot), “that in the beginning, matter in a state of ferment brought this world into being.” In other words, Diderot now claims that an active, vital, dynamic principle of change within matter itself—this is what brought the world into being and gave it such impressive yet imperfect order as it has. Jesuit theologian Michael J. Buckley explains: “Matter is no longer the inert, geometric extension of Descartes, nor the Newtonian mass identified with inertia and known only through its resistance to change. Now matter is the creative source of all change. … Matter now emerges as the ceaseless cause of all things.” This dynamic materialism, this vision of matter as intrinsically endowed with vital force—according to Diderot this is sufficient to produce this world by “evolution from chaos.” No Designer necessary. A rhapsodic Voltaire practically begged Diderot to come join him for philosophic conversation, while also expressing his concern that outright atheism might be going too far. Diderot replied (June 1749) that the deism-atheism debate hardly mattered to him any longer. “It is very important not to mistake hemlock for parsley; but it is not at all important whether you believe in God or not.” Wow!

The Letter on the Blind was such a moving argument for atheism, particularly as coming from the mouth of “Saunderson”—who speaks from his death bed, no less—that Diderot was awarded by the authorities three months holiday in the medieval fortress (dungeon) of Vincennes outside Paris. Captivated readers meanwhile consumed three editions of the Letter before year’s end!

So what do we learn from Diderot’s inertial atheism? Apologetics is a vital aspect of the church’s mission. This is especially the case in a critical culture. Worn down by over a century of Enlightenment criticism, the church that Diderot knew had largely retreated from public defense of the faith. As a result, when the sturdy old inferences from motion and design were newly contested and no longer struck culture as axiomatic, the frailty of Christian cultural engagement was easily mistaken for a frailty in the Christian creed. Inertia outmoded the Prime Mover. Dynamic materialism demythologized the Designer. And the church had little left to offer a doubting Diderot. But Christianity has far more to commend it to a doubting culture than the likelihood of the existence of an anonymous Higher Power. Where, for example, were undaunted and forthright arguments for the resurrection of Christ or the reliability of Scripture? Where was the Pascal for the 18th century to call attention to the profound explanatory force of the doctrine of original sin or to the teleology of human desire? Back in 1998, my colleague and fellow-blogger John Hutchison (who at the time was my teacher!) pointed out that the argument from design can only work well if it does not work alone. In this regard, believing in God is sort of like loving one’s spouse. A single copy of the official marriage license may convince the IRS, but it won’t sustain the marriage.

The church of Diderot’s day was arguing with neither confidence nor a full deck of evidence. And so it was that Diderot came to stand at the fountainhead of modern atheism. The following century saw merely a change in tactics, not general strategy, when Darwin’s natural selection supplanted Diderot’s dynamic materialism as chief rival to the argument from design. By contrast, what a full and formidable deck of evidence—remarkable in its scope and generosity and relentlessness—assembled by Christian thinkers in recent generations! Let’s thank God for that. And let’s continue to ask God to raise up apologists for his church in the 21st century.

A final note on Diderot. As it turns out, his dynamic materialism was lethal not only to his belief in God, but also to his belief in human freedom. If jittery, semi-divine atoms are the exclusive cause of the entire universe, they’re also the exclusive cause of the entire human person, including our most intimate thoughts and feelings. Molecules in motion is all we are. There is no need for an immortal soul, no basis on which to affirm human freedom. Diderot’s view entails determinism. And it is here that Diderot did acknowledge (in a way) that he’d gone too far. His own humanity was too rich and full for him not to realize that there’s more to life than atomic fate. He couldn’t stand the thought that something as profound as human love is just a wild jumble of atoms, and he confessed to his mistress, “I am furious at being entangled in a confounded philosophy which my mind cannot refrain from approving and my heart from denying.” Alas that no thoughtful Christian could be found to tell Diderot that his heart was right.

Biola University

Biola University

.jpg)