The Aug 15th issue of TIME magazine has a short piece on Rembrandt and his portraits of Christ. According to the writer, Richard Lacayo, Rembrandt in his early 40s began to evolve in the way he depicted Christ, changing from "turbulent scenes in the Gospel, full of sharp light and emphatic gestures, to smaller, contemplative groupings.” This shift in artistic emphasis represented a more profound concern in the artist. What he began to seek was something more than a fiery and enigmatic ideal human Christ—the subject of his earlier paintings—who partook of our humanity generally. Rather, he sought a compassionate Christ, one who could both identify and sympathize, represent and understand; he sought a “consoling Christ, quieter, more meditative, somebody who would listen.”

In the end, Rembrandt did what few artists to his day attempted—he rendered the Son of God as a normal Jewish man who intimately shared experiences common to all humanity. Lacayo writes:

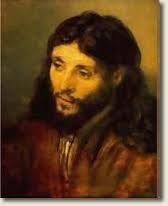

Rembrandt's rethinking of Christ is even more evident in a series of utterly human images, small oils on wood panels, that were painted in the late 1640s and early '50s. (Some were the work of his studio assistants in imitation of their master.) Putting aside centuries-old conventions of depicting an otherworldly Christ, Rembrandt made him unmistakably of this world, a young, bearded man with long, dark hair and soulful eyes, someone you might meet on any street. Literally. The model who sat for this series may have been a Sephardic Jew from Rembrandt's Amsterdam neighborhood.

The artist’s supposed cry of the heart points to the gospel logic of traditional Christology. That Christ was a man in the truest sense is at the heart of the good news: “For what was not assumed,” writes Gregory of Nazianzus, “is not healed.” The framers of the Definition of Chalcedon make a similar connection when they speak of Christ as

of one substance with the Father as regards his Godhead,and at the same time of one substance with us as regards his manhood; like us in all respects, apart from sin; as regards his Godhead, begotten of the Father before the ages, but yet as regards his manhood begotten, for us men and for our salvation, of Mary the Virgin, the God-bearer; one and the same Christ, Son, Lord, Only-begotten, recognized in two natures, without confusion, without change, without division, without separation . . .

While Jesus Christ is certainly more than just merely human, his humanity is like ours in all respects, sin excepted. The Definition’s “without confusion” preserves the genuine humanity of Christ, a humanity necessary for the fulfillment of his ministry “for us and for our salvation.” Jesus became a man for us. Or even better, as the author of Hebrews puts it:

Since the children have flesh and blood, he too shared in their humanity so that by his death he might break the power of him who holds the power of death—that is, the devil—and free those who all their lives were held in slavery by their fear of death. For surely it is not angels he helps, but Abraham’s descendants. For this reason he had to be made like them, fully human in every way, in order that he might become a merciful and faithful high priest in service to God, and that he might make atonement for the sins of the people. Because he himself suffered when he was tempted, he is able to help those who are being tempted. (Heb 2:14-18)

For we do not have a high priest who is unable to empathize with our weaknesses, but we have one who has been tempted in every way, just as we are—yet he did not sin. (Heb 5:18)

Surely the “for us” of Chalcedon includes the mercy and empathy of Hebrews’ Christ.

Let our Christology, then, imitate art, or rather the artist; let us seek the compassionate Christ. We have reason to take comfort, for the Christ Rembrandt sought is the Christ of Scripture.

Biola University

Biola University

.jpg)

.jpg)