I was discussing the topics of Gnosticism and Monarchianism with my students in class recently and asked them a question: what do these two views have in common? The answer: a very divisive or bifurcated view of reality.

Both views are characterized by a dualism, which celebrates the spiritual realm but denigrates the physical realm. On the one hand, Gnosticism views the physical world as a cosmic accident, and consequently has a very low view of material reality. On the other hand, Monarchianism posits a sharp distinction between the eternal and temporal realms, and a corresponding division in God’s character: between who he is and how he has revealed himself to us.

I went ahead and asked the class another question: can you think of ways in which the church continues to struggle with dualism today? Interestingly, the discussion eventually led to the observation that there is a general lack of admiration for sacred space and art in the evangelical church culture with its lopsided emphasis on the spiritual.

As I was putting my thoughts together for this post few days ago, I made a serendipitous discovery that the recent edition of Biola magazine actually deals with this very theme!

Have you walked into an evangelical place of worship recently and seen inspiring architecture or art? Chances are, like me, you might have visited churches where the sanctuary doubled-up as a basketball court during the week. Now, I do not think that there is anything particularly wrong with this arrangement from a biblical or theological standpoint. Perhaps, due to pragmatic and or even valid reasons, a particular group of believers might have decided that this is the best way to make use of space available to them.

God’s presence is not circumscriptive but repletive, which means He is not restricted by space, He is present everywhere. Moreover, Jesus reminded the Samaritan woman that it is not the where (“this mountain or in Jerusalem”) but the how (“in spirit and truth”) of worship that is important (John 2:21ff). And Paul calls us the temple of God’s Spirit (I Cor 6: 19–20). In this sense, all space is sacred, we do not need to create a space and christen it as sacred in order to pray and worship—we can do that wherever we are.

I began to consider the Christian use of sacred space and art during my visit to Istanbul two summers ago, where I spent some time thinking about architecture and art in the early church while revising a biographical chapter for a forthcoming book on John Chrysostom’s Christology. I got to visit the Church of St. George, the official church of the Greek Patriarchate, where the present successor of Chrysostom—and the leader of all Eastern Orthodox churches—lives. The Patriarch’s secretary, with whom I had made a prior appointment, gave me a personal tour of the premises, and talked about the ministries of the two former celebrated bishops of the city once called Constantinople: Gregory of Nazianzus and John Chrysostom. I was mesmerized by the splendor of the church as we walked around, while people talked in hushed tones as they admired the architectural beauty of the high columned sanctuary, gazed at the ornate gilded iconostasis, and considered the delicate in-laid woodwork of the refurbished pulpit made from the remnants of the original one used by the golden-mouthed preacher (Chrysostom). A visit to such places definitely inspires awe, directing one’s attention to the glorious beauty of God.

The fathers of the church talked about God using tangible means, even matter itself, to communicate his grace and presence to us. And the key idea that undergirded this sacramental view of reality was the incarnation of God in Jesus Christ. God who created matter entered the material world: the eternal Word became flesh and tabernacled among us. The divine and human natures, spirit and matter were united in our Lord. The tabernacle imagery of the incarnation inspired architecture and art in the early church. Therefore, sacred space and art functioned as theological statements and represented profound biblical truths in non-verbal ways.

I witnessed this in what is considered a masterpiece of Byzantine architecture: the Hagia Sophia, the Church of the Holy Wisdom of God. The ambiance created by the golden haze of the interior decorated with precious stone and mosaic has an overwhelming effect on visitors. The sheer dazzling beauty of church with its magnificent play on space, light, and color provokes worship in the believer!

As I stood in the sanctuary imagining how Chrysostom would have preached about the transforming power of the Gospel to crowds where the present edifice stands—for Justinian built the Hagia Sophia in place of the former episcopal church—I was reminded that even after more than a millennium, the beauty and awe inspiring nature of this sacred space has not diminished, but continues to direct one’s attention heavenward. Further, such was the profound influence of this prominent church in the Christian East, that it eventually became an architectural template for other religious edifices in the Ottoman Empire.

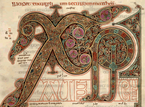

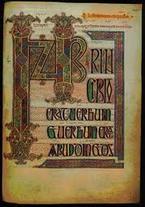

Sacred art like illuminated manuscripts had a pedagogic function in the early church. The fathers’ high view of the written Word led to the careful preservation and transmission of texts. Just as in the incarnation, where the glory of the Word is veiled in flesh, so in the Scripture the glory of Christ is veiled in the text. The reader was reminded that beauty of the text reflected the beauty of the Word made flesh. Insular Christian art has had a profound influence on calligraphy in the eastern and western world. For instance, the Lindisfarne Gospels are not only acknowledged as one of the most important manuscripts in the development of medieval art, but are also recognized as a crucial document in the history of Western Christianity. They are fine examples of monastic book illumination and contain the earliest surviving English translation of the gospels. Long after the legions abandoned Britain after the fall of Rome, the monasteries along the sea-battered and stormy coasts of Scotland (Iona), Ireland (Skellig Michael), and England (Lindisfarne) functioned as vital centers of Christian civilization. The scripts devised and the books produced in Lindisfarne and Iona at this period became the common form of writing during the Middle Ages.

Given this marvelous heritage, I have often wondered if the lack of interest in the external beauty of sacred space and décor, which characterizes much of our church culture today, is due to the struggle with dualism? Or is it due to the residual sense of over-correction that we have inherited from the Reformation movement? I suspect it may be both.

During the sixteenth century in an effort to bring the church back to its biblical foundations, the Reformers rightly took a firm stand against objects—representational or non-representational—in the sanctuary that became a source of distraction. The preaching of Word occupied center stage and anything that overshadowed the ministry from the pulpit was done away with. But, does this mean there is no room for good architecture and art in the church today? The Reformers were not against art or its use in the life of faith. Luther was open to the use of sacred art in the church as long at it was not distracting and Calvin spoke of art as a gift of God. Moreover, Calvin encouraged Huguenot refugees in Geneva to use their artful jewelry-making skills for God’s glory, which led to the emergence of the Swiss watch making industry. The Reformers thought of the glory of God as his manifested excellence, and viewed him as the supreme artist and builder who is Lord over all creation. The Dutch theologian and statesman Abraham Kuyper captures this remarkable Reformation perspective with the following statement: “There is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is sovereign over all, does not cry: “Mine!” Thus our aesthetic sense, and use of sacred space and art must reflect this truth.

I am not suggesting that we embark on a cathedral building enterprise or start to venerate icons, but I certainly think there is room for improvement in our biblical and theological understanding of God glorifying sacred space and art. I am thankful, however, that we have begun to turn the corner in the evangelical church with the help of gifted artists who are reconnecting Christian faith with fine art.

Biola University

Biola University

.jpg)

.jpg)