I was raised in a church world in which “culture war” was a favorite metaphor of how the church relates to the nonchurch. We were God’s courageous moral infantry doing battle against those cunning cultists, those hateful homosexuals, those lying liberals, and those devilish Darwinists. If we listen with tuned ears to Christian radio, Christian literature, Christian blogs, and Christian conversations, it becomes clear: We Christians love the language of war. Over the last 30 years it has become our dominant metaphor for relating to culture; it saturates our vocabulary, shapes our politics, and soaks our worldview. But is culture war helpful? Is it biblical? Should we be jarheads for Jesus?

I offer 10 reasons that we need to permanently jettison the culture war metaphor as the church moves into the future:

REASON 1: Culture war blurs important biblical distinctions regarding evil, moving us to battle the wrong “enemy.

What if the Allies of World War II had declared war against Holland, marching on the Hague to dethrone Queen Wilhemina, while the rampaging Fuhrer of Berlin continued his vicious blitzkreig unopposed? Such a witless Allied blunder would have been cataclysmic. As Sun Tzu observed in The Art of War, you must “know your enemy.”

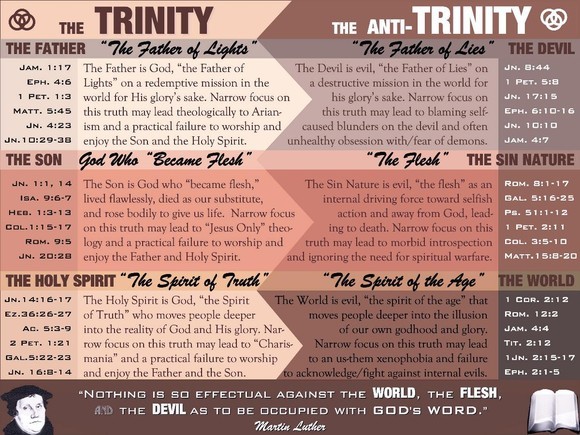

When looking through biblical lenses, we begin to see evil not in monochrome, but in three dark hues. We behold what we might call an “anti-Trinity” of forces ambushing the Triune God’s good mission for His universe (Click here for more on the anti-Trinity). In the Trinity we have God, ‘the Father of Lights;’ in the anti-Trinity, the devil who is the ‘Father of Lies.’ In the Trinity we find Jesus, ‘the Word made flesh;’ in the anti-Trinity, we encounter our internal sin-drive that Paul calls ‘the flesh.’ In the Trinity we meet the Holy Spirit called ‘the Spirit of truth;’ in the anti-Trinity, the world, or ‘the spirit of the age.’ These important distinctions are captured in the infographic below:

The Bible’s distinctions between the world, the flesh, and the devil, are massively important to the question of whether or not we should engage in culture war. Should we war against the devil? Yes. Paul calls us to prayerfully armor up “against the schemes of the devil,” “extinguishing all the flaming darts of the evil one,” wielding the Word of God to assault God’s ancient enemy (Eph. 6:10-20). As Calvin put it in his commentary on 2 Corinthians 10, “The life of a Christian, it is true, is a perpetual warfare, for whoever gives himself to the service of God will have no truce from Satan at any time.”

Should we war against the flesh, those internal anti-God propensities that are “waging war against our souls" (1 Pet. 2:11 cf. Jam. 4:1), “making us captive to the law of sin” (Rom. 7:23)? Again, the Bible issues a call to war: “Put on the armor of light… [and] put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh, to gratify its desires” (Rom. 13:12b, 14). With violent language, Paul calls us to mortify or “kill” the flesh by the Holy Spirit’s power (Rom. 8:13), to execute or “crucify” it (Gal. 5:16-24).

So is Christianity a religion of war? If our enemies are the Flesh and the Devil then yes, onward Christian soldiers! If, however, our enemy is the world, then the Bible has something else to say. First, we are commissioned, not to live in a bubble like a world-a-phobic tribe, but to go into the world to herald the good news of Jesus (Matt. 28:19). Second, we don’t go as chameleons absorbing into our skin any Christ-less colors of the broader culture, but as non-conformists (Rom. 12:2), “unstained from the world” (Jam. 1:27), “shining as lights... in the midst of a crooked and twisted generation” (Phil. 2:15). We refuse to become slaves, victims, friends, or lovers to an oppressive system in which greedy consumption, radical self-glorification, and constant pleasure-center brain stimulation are hailed as virtues (Gal. 4:9; 6:14; Jam. 4:2-4; 1 John 2:16-17). Third, as we go, the Bible warns that the world might very well take an aggressive posture of hatred toward those who refuse to conform to its values (John 15:18-19; Matt. 10:22, 25).

When the hatred comes, is that time for the church to beat our plowshares into swords and counterattack with culture war? On the contrary, Jesus commands (not suggests) not that we retaliate or even merely tolerate, but that we “Love our enemies” (Luke 6:27 cf. 6:35). This is the same Jesus who prayed for the salvation of the very men hammering spikes through his wrists, the same Jesus who bled for us when we ourselves were warring against the Father He loves. Paul, following this radical countercultural pattern of enemy-love (and no stranger to the world’s brutality himself), commands blessing to the persecutor, peaceable living with all, a ban on vengeance, food for the hungry enemy, and goodness to overcome evil (Rom. 12:14-21). It is significant that neither Jesus nor Paul, nor any Spirit-inspired author commands us to love, bless, make peace with, or feed either the devil or the sin-drives in our own hearts.

When pondering war, therefore, the Christian must ask: Is the object of my warfare the flesh or the devil? If so, then fight on. If, however, the church feels assaulted by a militant culture, we need to postpone our natural fight-or-flight response long enough to ponder the unnatural command of Jesus and Paul to meet the force of hatred with the force of love. And we must pray for the supernatural infusion of love necessary to live such an impossible and countercultural command.

REASON 2: Culture war misses the biblical distinction between combatants and captives, mistaking a mission of liberation as one of extermination.

A Christian culture warrior may object, ‘Yes, the Bible does call us to war against Satan. But as “the ruler of this world” (John 14:30); Satan enlists human soldiers to carry out his diabolical orders. Therefore, you can’t engage in spiritual warfare without simultaneously waging a culture war.’ I agree with this objection insofar as I believe, with Scripture, that there is more than mere human evil at work in culture. I do not believe Satanic forces were distant and disinterested spectators to the concentration camps. However, arguing to a war-on-culture from a war-on-Satan overlooks another important biblical distinction. Consider Paul’s words:

And the Lord's servant must not be quarrelsome but kind to everyone, able to teach, patiently enduring evil, correcting his opponents with gentleness. God may perhaps grant them repentance leading to a knowledge of the truth, and they may come to their senses and escape from the snare of the devil, after being captured by him to do his will. (2 Tim. 2:24-26).

Paul does not picture his human opponents as soldiers in Satan’s army to be met with lethal force. Rather, they are described as snared captives who must be met with kindness, gentle correction, and a hopefulness that works not toward their extermination but their liberation (cf. Luke 4:5-6; Eph. 2:2). Peter summarized Jesus’ ministry to the world not as smiting Satan’s soldiers, but as “doing good and healing all who were oppressed by the devil” (Acts 10:38 cf. Luke 11:21).

Soldiers make war. Paul calls us to “live peaceably with all” (Rom. 12:18 cf. Heb. 12:14; 1 Pet. 3:11). A soldier sheds his opponent’s blood; Paul sheds tears for his (Phil. 3:18). A soldier becomes cold-hearted toward the enemy; Paul had “unceasing anguish in [his] heart” for those who opposed him (Rom. 9:2). A soldier puts a higher premium on his own survival than that of his enemies; Paul wished to be “accursed and cut off from Christ” for the sake of his unbelieving brothers (Rom. 9:3). Paul was imprisoned, impoverished, battered half to death, and finally decapitated by Nero’s executioners. And all to carry out his mission, not to put x’s on his enemies’ eyes, but “to open their eyes so that they may turn from darkness to light and from the power of Satan to God, that they may receive forgiveness of sins” (Acts 26:18).

Again, it is significant that nowhere does Jesus, Paul, or any biblical author command gentleness toward, cry for, have internal anguish for, seek peace with, or suffer and die for the liberation and life of the devil or the flesh. Yet he does all of that and more that the world may see and savor Jesus. From these biblical distinctions, it follows that war-on-Satan does not entail war-on-culture. Our aggressive acts of war against the devil must be matched by empathetic acts of abolition for our neighbors who remain trapped in the oppressive grip of history’s oldest human trafficker.

THE METAPHORS MATTER

Am I arguing that a post-culture war Christian no longer offers meaningful critiques of hurtful and dehumanizing ideologies that shape culture, no longer cares about politics, no longer challenges and converses with those beyond his own spiritual tribe? Of course not. The call of Jesus was never that of a cult leader to coax us from society, buy guns and gold, and move to a secluded mountain compound where we all drink Kool Aid and bid farewell to the world’s problems. Jesus commissions us to go into the world. What I am arguing is that the culture war metaphor has a profound, often subconscious effect on how we go about obeying Jesus’ commission. Are we going more as disciple-makers or enemy-slayers? Is culture more of a field to plentifully harvest or an army to be vanquished? Are we more like abolitionists on a mission to liberate people in chains, or a Seal team on a search-and-destroy mission? How shall we then live in the “post-Christian age,” like a jarhead or like Jesus, trying to kill or willing to die for our enemies?

The metaphors matter.

To be continued in Part 2 of “Jarheads for Jesus?: 10 Reasons ‘Culture War’ is a Really Bad Metaphor.”

Biola University

Biola University

.jpg)

.jpg)