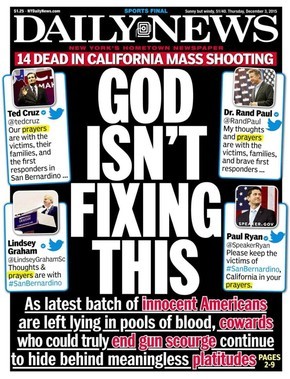

"GOD ISN’T FIXING THIS," New York’s Daily News announced in the aftermath of the latest US mass shooting, in San Bernardino. Their target? Presidential candidates who immediately responded to the tragedy by offering sufferers their “thoughts and prayers,” not calling for more gun control.

"GOD ISN’T FIXING THIS," New York’s Daily News announced in the aftermath of the latest US mass shooting, in San Bernardino. Their target? Presidential candidates who immediately responded to the tragedy by offering sufferers their “thoughts and prayers,” not calling for more gun control.

The headline’s sentiment is widely shared, as seen in the flood of “prayer shaming" by celebrities, politicians, and other pundits on Twitter (#prayershaming) and various online media. Many voices ridicule prayer itself (and religious, especially Christian, beliefs and practices more generally) as meaningless; others merely criticize it as a response to tragedies like this.

The widespread appeal and public acceptance of the former—in-your-face ridicule and contempt of traditional religion—is troubling. It’s also enlightening in making vivid the realities of today’s American religious landscape. Some fine thinkers (and pray-ers, no doubt!) have weighed in on prayer shaming.

But what about the latter, more modest charge, that “thoughts and prayers” is simply the wrong response to tragedies like this? It needs some further thought as well.

First, let’s acknowledge that the “thoughts and prayers” slogan is often merely a politically acceptable (until now!) platitude, offered with little thought or prayer.

Even for nonpray-ers, however, it may reflect something much deeper and primal, expressed in the only language they find available—a cry of empathy with sufferers, and an appeal for some kind of ultimate love (and justice), which, at a deep level, everyone intuitively knows can only come from something or someone far greater than ourselves.

In any case, let’s focus on the actual “thoughts and prayers” of religious believers, and specifically of followers of Jesus—readers of this blog and, it’s pretty clear, the primary targets of the bulk of the prayer shaming.

And let’s stick to the “prayers” part; no one seems bothered about “thoughts” (no #thoughtshaming hashtags). In any case, Jesus calls his followers to pray for those who suffer, not merely think of them. (Thinking of them can help us become more compassionate or empathetic, but it hardly helps them right now.)

So how could prayer, however sincere and deliberate, be a legitimate response to tragedies like this?

Well: prayer as opposed to what? If offering prayers is the wrong response, what is the right one in view? Doing something—in this case: calling for more gun control.

But of course, praying for those who suffer is doing something.

And praying in these circumstances is obviously compatible with also doing something else.

Indeed, Christian teaching on prayer has always emphasized that we should not only pray, we should also work. Orare et labore: pray and work. The kinds of work the Bible endorses come in many, many forms.

Work Jesus calls his followers to do also includes some very specific things like feeding the hungry, clothing the poor, comforting the afflicted, nursing the wounded and protecting the innocent. The latter is what the Christian pastor/policeman was doing when he was killed during the rampage in Colorado Springs a week before San Bernardino.

Followers of Jesus are certainly not the only ones doing these things. But they do have a way of consistently showing up where there are needs and quietly helping meet them.

Including tragedies. Hundreds of Jesus followers, from specialists like Samaritan’s Purse response teams to men, women, and children from local churches, have been and are now at sites of tragedy such as San Bernardino, meeting physical, emotional, and spiritual needs—embodying God’s love, comfort, peace and hope in tangible form.

What about gun control, the preferred immediate response to the tragedy? In my view restricting legal access to automatic weapons is a vital part of helping reduce some of the future gun violence (it wouldn’t touch the vast criminal sources or the terrorist ideologies that fuel many of the worst of these tragedies). But how does calling for gun restrictions or even enacting them help these sufferers now—the people we’re actually talking about helping? The doing that began almost immediately in the aftermath of this tragedy, much of it by Christians, is what actually meets the desperate needs of injured victims, their families, and their community.

Prayer shaming ignores the fact that those who truly pray usually do much, much more than that.

Okay. So why not just stick to the “much, much more”? Why pray?

For one thing, most of us who offer “prayers” at times like this simply aren’t in a position to go to the scene of a tragedy and help in these other ways. Indeed, in the immediate aftermath, nearly everyone, even those who will get there to help, has only the smallest awareness of what’s fully going on. What do we actually have to offer now, other than prayer?

Is that enough? For some of us, those who cannot do more, it may be. But in fact, it’s much more than “enough.” Even as our awareness of the situation grows, even if we are able to do more, praying for the suffering is vitally important work. It plays crucial roles in helping sufferers that even giving physical aid (much less gun control) simply can’t.

Suffering is not only physical. It’s also emotional, psychological, relational and spiritual. Victims and their families have internal wounds and struggles; some find this pain equal to or even greater than that of their external wounds. Sufferers need comfort, love, a taste of goodness, a measure of peace. They need hope.

God specializes in meeting these kinds of needs. Indeed, at the deepest level, only he can. Only God provides, for example, “peace that transcends all understanding” (Philippians 4:7)—something many sufferers through the ages, including me, have experienced.

This in no way downplays the importance for believers also to embody God’s comfort, love, peace, and hope in tangible ways. Orare et labore. But ultimately these needs go too deep for anything other than the internal, mysterious work of God himself in our lives. Even believers who are called to minister physically with sufferers do so prayerfully, and are often asked—by them—to pray with them.

What should we pray?

Prayer shamers may worry that Christians will only serve—and even pray—in such situations in order to “proselytize.” But response teams don’t check someone’s religious status before treating them. Suffering is suffering, needs are needs—which responders are there to help meet. When Jesus called his people to minister to the thirsty as unto him, he said to give them something to drink, not a gospel tract (Matthew 25:41-44).

The same goes for praying. We pray for sufferers’ needs—all of them, including but not only their spiritual needs. As Paul spoke of the “kindness” of God expressed in physical provisions given to all people, believers and nonbelievers alike, tangible kindness that “fills their hearts with joy” (Acts 14:17), we can pray that sufferers would experience the touch of God’s kindness in all their areas of need.

And of course, we may also pray that sufferers who “taste the goodness of God” as he touches them in these ways during this time, would hunger to know the fullness of his goodness found in Jesus (1 Peter 2:2-3).

In any case, here’s good news: Even in the immediate aftermath of a tragedy like this, when no one is yet able to offer physical help of any kind, all of us can already be busy doing the holy work God has given all of his people to do. We can pray.

Biola University

Biola University

.jpg)

.jpg)