In his forthcoming summative book, called Beyond the Texts, the Syro-Palestinian archaeologist William G. Dever summarizes what is presently known about ancient Israel and Judah based primarily on the artifacts—the material culture that includes textual sources. One example is Dever’s portrait of the historical King David. He offers the following seven propositions about David that are inferred from archaeology and also converge with what is attested in biblical texts.

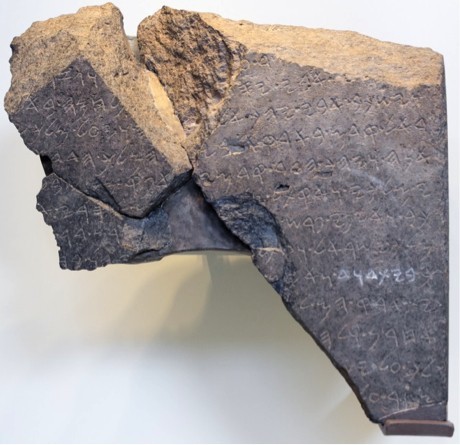

- “David did exist as a king, the head of at least a nascent 10th-century B.C.E. state (cf. the well-known Tel Dan Stela …).

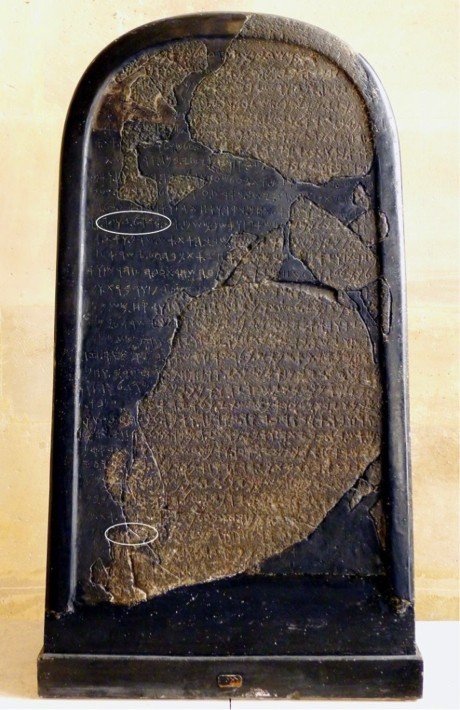

- He founded a dynasty, well known to his neighbors (cf. the Tel Dan Stela and possibly also the Mesha Stela from Transjordan…). [See photos below.]

- He embellished his capital in Jerusalem (the Stepped Stone Structure and the ‘Citadel’ recently excavated by Eilat Mazar). [For further discussion and photographs of these structures, see my earlier blog post.]

- His reign saw an expanding population and an increasing urbanism (settlement patterns).

- He fortified the borders of the kingdom (Khirbet Qeiyafa as an early-10th-century B.C.E. well-planned barracks-town on the border with Philistia). [See photos below.]

- He was successful in his wars against the Philistines (comparative stratigraphy of Judahite and Philistine sites, showing the weakening of the latter).

- His national dynasty and ‘Israelite self-identity’ lasted from the 10th to the early sixth century B.C.E. (continuity of a distinctive material culture).” - Excerpted from Dever’s recent article in Biblical Archaeology Review (43.3 [2017] p. 47).

The first and second points, mentioning David’s name and dynasty in monumental inscriptions, deserve some further explanation, since a few of these texts are now known. First, the mention of “the House of David” (byt-dwd) in the Tel Dan Stele, line 9, is written in Old Aramaic on a basalt fragment that was excavated in 1993 under the direction of Avraham Biran (see Biran and Naveh 1993; cf. Ahituv 2008). The reading is certain, dating to 841 B.C.E., which is about 130 years after the time of David (assuming that David reigned 1010-970 B.C.E., based on biblical chronology). The three extant fragments of this stele are now on display in the Israel Museum (Jerusalem).

Second, another mention of “the House of David” (bt-[d]wd) likely occurs on the Mesha Stele, line 31, which was written in Moabite and partially reconstructed based on a squeeze of the inscription that was made in 1869 before the stele was broken and its pieces were scattered (see Lemaire 1994; cf. Ahituv 2008:395, 417). This reading is plausible, dating to 851 B.C.E., which is about 120 years after the time of David. The recovered fragments of the Stele and the squeeze are now located in the Louvre Museum (Paris). Incidentally, the name David also seems to occur earlier on the Mesha Stele (line 12) where there is a reference to “its Davidic altar hearth” (’r’l.dwdh), that is, the Gadite altar-hearth in ‘Ataroth from King David’s time (see Rainey 2001:296, 306; cf. Ahituv 2008:394, 406-407).

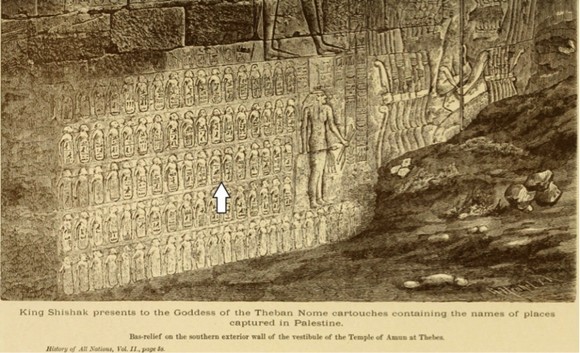

Third, Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen suggests that the phrase “[he]ig[hts] (of) David” (hadabiyat-dawit; name-rings 105+106) may be found in the Egyptian Topographical List of Shishak/Shoshenq I (see Kitchen 2017:17). Whereas the two previous mentions of “the House of David” were regarded as “certain” and “plausible” respectively, this tentative reading must remain as only possible. The Topographical List contextually locates the reference to David’s heights in the Negev area (by geographical association), and it dates to 925 B.C.E., which is about 45 years after the time of David—that is “within living memory of the man” (Kitchen 2003:93). Today the remaining fragments of the Topographical List are still located at Karnak (Temple of Amun; Bubastite portal); see photo of early drawing below.

All of this amounts to an impressive heap of archaeological evidence for the historical King David, in case one ever needs to reach “beyond the [biblical] texts” in order to show areas of convergence between the Bible and archaeology or to corroborate historical claims that are made by the Bible.

Biola University

Biola University

.jpg)

.jpg)