About half the world is made up of women. Books such as Half the Sky (Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn) and Half the Church (Carolyn Custis James) highlight how important it is for the Evangelical church to consider God’s vision both locally and globally for women. In the light of the Gospel, the church during the Reformation also wrestled with women’s place, in the church, marriage, and society. While the Protestant Reformers did not set out to define women’s roles, as they fleshed out their theological convictions of sola Scriptura and the priesthood of all believers, they were faced with addressing the question of how women are to participate in the church and the world as both receivers and conveyors of the Gospel. Did the Reformers’ responses result in “constraining” women by moving their ministry from the convent to the home (as Jane Dempsey Douglass argues), or did it provide them with “new dignity” (as Stephen Nichols suggests)? The answer to that question is complicated.

About half the world is made up of women. Books such as Half the Sky (Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn) and Half the Church (Carolyn Custis James) highlight how important it is for the Evangelical church to consider God’s vision both locally and globally for women. In the light of the Gospel, the church during the Reformation also wrestled with women’s place, in the church, marriage, and society. While the Protestant Reformers did not set out to define women’s roles, as they fleshed out their theological convictions of sola Scriptura and the priesthood of all believers, they were faced with addressing the question of how women are to participate in the church and the world as both receivers and conveyors of the Gospel. Did the Reformers’ responses result in “constraining” women by moving their ministry from the convent to the home (as Jane Dempsey Douglass argues), or did it provide them with “new dignity” (as Stephen Nichols suggests)? The answer to that question is complicated.

The Protestant Reformers' study of Scripture and the resulting conviction of the equality of all believers before God led them to initiate changes in the way education, the church, family, and societal structures were conceived. As a result of the Reformation, women were given new opportunities to be educated, participate in the church and in the family, and share the Gospel.

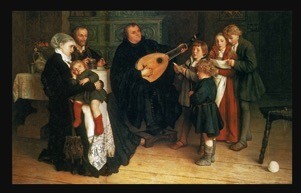

Martin Luther proclaimed the priesthood of all believers, teaching that both men and women were equal before God and free to pursue their God-given vocational callings. This concept elevated the status of both the homemaker as well as the farmer in the field. The hierarchy was no longer to be valued above the lay person. Changing diapers and milking cows were holy work. In his treatise, To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation, Luther wrote:

It is pure invention that pope, bishop, priests, and monks are called the spiritual estate while princes, lords, artisans, and farmers are called the temporal estate. . . all Christians are truly of the spiritual estate, and there is no difference among them except that of office. Paul says in 1 Corinthians 12:12-13 that we are all one body, yet every member has its own work by which it serves the others. This is because we all have one baptism, one gospel, one faith, and are all Christians alike … we are all consecrated priests … as St Peter says in 1 Peter 2:9, ‘You are a royal priesthood and a priestly realm.’ The Apocalypse says, 'Thou has made us to be priests and kings by thy blood’ [Rev. 5:9-10].

By all Christians, Luther meant women as well as men. No longer was a woman to be considered “defective and misbegotten,” as Aquinas had taught, but created in the image of God and of infinite value. In Christ, all Christians are consecrated priests. Therefore, Luther referred to his own beloved wife Katie, a former nun, as “my rib,” my book of Galatians, and the “boss of Zulsdorf” (the Luthers’ farm). He called marriage the “school of character” and encouraged a husband to take his wife’s opinion into account and not seek to “demonstrate his masculine power and heroic strength by ruling over his wife.” Furthermore, Luther even encouraged men to love their wives selflessly and sacrificially, like Christ loves the church. “Man cannot do without women” and should not listen to the harlot of reason that says:

Ah, should I rock the baby, wash diapers, make the bed, smell foul odors, watch through the night, wait upon the bawling youngster and heal its infected sores, then take care of the wife, support her by working, tend to this, tend to that, do this, do that, suffer this, suffer that, and put up with whatever additional displeasure and trouble married life brings? Should I be so imprisoned?

Instead, the godly man should seek to serve his wife and family saying:

I confess to thee that I am not worthy to rock the little babe or wash its diapers. or to be entrusted with the care of the child and its mother. How is it that I, without any merit, have come to this distinction of being certain that I am serving thy creature and thy most precious will? 0 how gladly will I do so, though the duties should be even more insignificant and despised. Neither frost nor heat, neither drudgery nor labour, will distress or dissuade me, for I am certain that it is thus pleasing in thy sight.

Though Luther’s understanding of the priesthood of all believers helped promote the value of women and marriage, it did not radically change women’s place in the church and in the world. Women were still to be submissive to their husbands and had limited options within either of these realms. While pastors wives now had new opportunities to influence their husbands and even participate in theological reflection, as evidenced in Katie’s involvement in some of Luther’s Table Talk discussions, the closing of many convents also limited women. Without the convent, many women lost the option to receive a higher education and pursue a calling to do ministry within the church. While the Reformation afforded new educational opportunities, many of them ended for women after youth. For example, in Geneva, John Calvin opened the doors for the young to be educated. No longer was education limited to boys born into families of wealth or position. But, it would be erroneous to say that Calvin was an Egalitarian. Women were excluded at the higher levels, due to education being directed towards preparation for church and community leadership roles.

Scholars have been tempted to either celebrate or lament these changes, seeing them as either a radical movement towards liberating women or as a reinforcement of gender inequality. Historical and theological evidence, however, provides a much more complicated picture of the impact of the Reformation on women's roles-- one that should be both celebrated and at times lamented. We should celebrate the recovery of the biblical understanding of the ontological equality of men and women, the priesthood of all believers, and the value of marriage. We should lament the loss of opportunities for women to commit their lives to the formal study of Scripture and service of the church. The convents allowed single women to pursue a vocational calling of a life of piety, service, and the study of the Scriptures within the safety of the church. Many Evangelical women today still struggle with the question of what is their vocational calling? How do they serve Christ and the church? The Reformation answered it in part by elevating the the role of wives and marriage. That answer, however, isn’t sufficient, for all women. The Evangelical church has the opportunity to re-examine this vital question on the eve of the 500th anniversary of the Reformation.

Biola University

Biola University

.jpg)