Visualizing Christian’s journey on the Progress Bunyan plots for him has taken numerous forms.

A few possibilities are showcased on book covers.

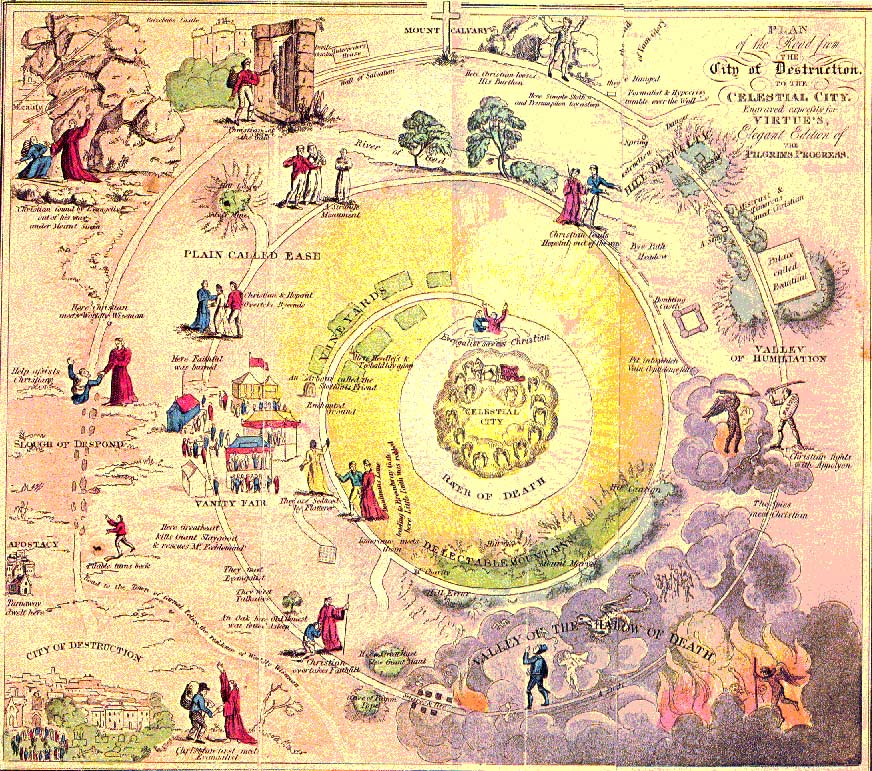

One that pops up quite a lot is the spiral map leading from the outer edges into the golden center of the Celestial City.

In my judgement, the circular maps tend to fit into a tradition that places Bunyan alongside his medieval predecessor in literary heavenly Pilgrimage, Dante. The circular, spiraling descent into Hell and then upwards to the degrees of Paradise gives us this image of the Dante’s pilgrim voyage. As such many suppose that, apart from allowing many details on the path to be coiled into a reasonable sized frame, the device is ill suited to the "straight and narrow" path that Bunyan’s Good-Will draws on from Jesus’ words in the Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 7:,14), as well as Bunyan’s polemical Protestantism. However, it is not clear that Bunyan distinguishes between straight and strait (meaning narrow). His orthography varies as spelling was less conventionally fixed in his day. Strait/straight could mean either or both of "linear in the same direction" or "narrow." So straight-ness/strait-ness which applies to the path is in order to fit the strait and narrow gate of Matthew 7, but need not speak to the actual course of the path beyond the gate while keeping its narrowness. Indeed, for those who read Bunyan’s allegory as an account of an internal spiritual journey where the topography is mostly incidental setting for psychological experience - even static passivity in the case of critic Stanley Fish - perhaps the going in circles of minimal distance as the crow flies, but a world of transformation accomplished inwardly, is intimated by these spiral maps. If indeed, as Bunyan states in his Author’s Apology, he hopes that the reading of his book will make a "traveler of thee," it is in the sedentary activity of reading, taking up the book he continuously points you to in his marginal notations, the Bible, that the journey is accomplished. This would help us see that, for example, the town of Vanity is still the same old City of Destruction that Christian is still in the midst of, despite his journey.

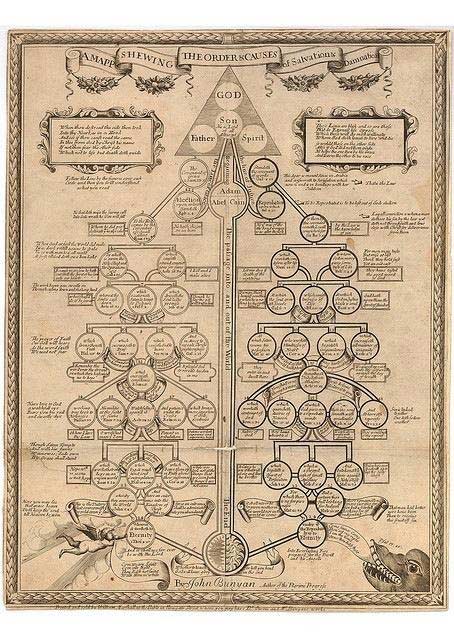

All right, but now back to linearity, before writing "The Pilgrim's Progress" John Bunyan had already set out a diagrammatic Map of Salvation (1663 or 64) – distinctive for its clearly distinguishing the two ways of eternal reward or damnation, and noted for its curious triangular Trinitarian symbol for God which then includes each person, Father, Son and Spirit. (Note Bunyan’s "Of the Trinity and the Christian" is one of his shortest writings, two and half pages to the effect that: Yes, the Bible says so!)

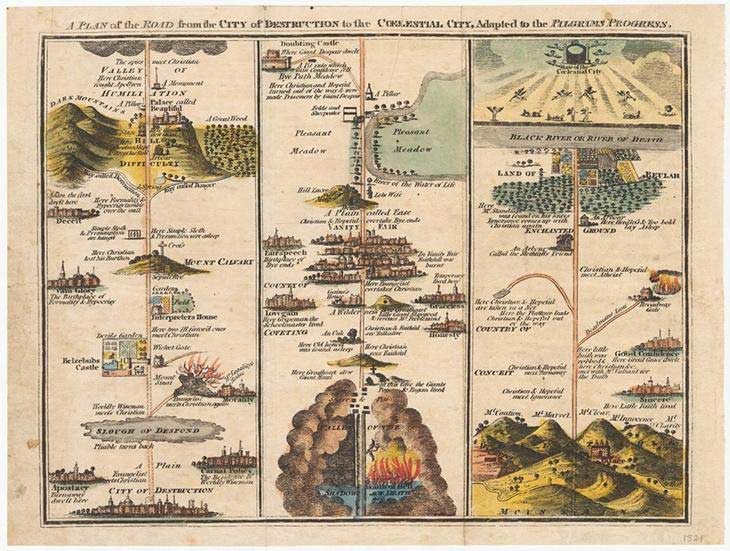

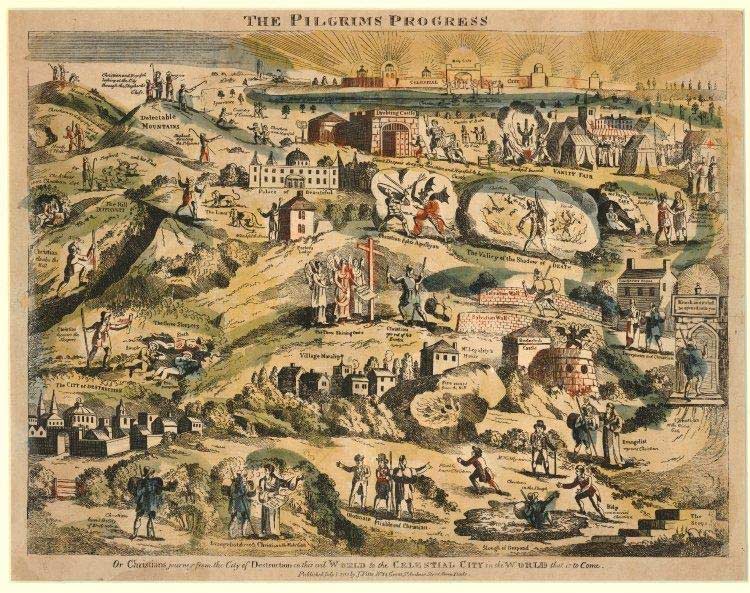

Linear maps seem more coherent if we take it that it is a straight and narrow way Christian is to follow, even if the challenge then becomes one of fitting it in a book. The cover of the Norton edition represents this in a threefold division, as shown more largely below in the accessible image from the University of Cornell’s digital collection (click to zoom in on detail).

Another 19th century version is held by the British Museum, which keeps some topographical unity to the depiction of narrative episodes, while heading upwards and at the same time criss-crossing the canvas for maximal story telling:

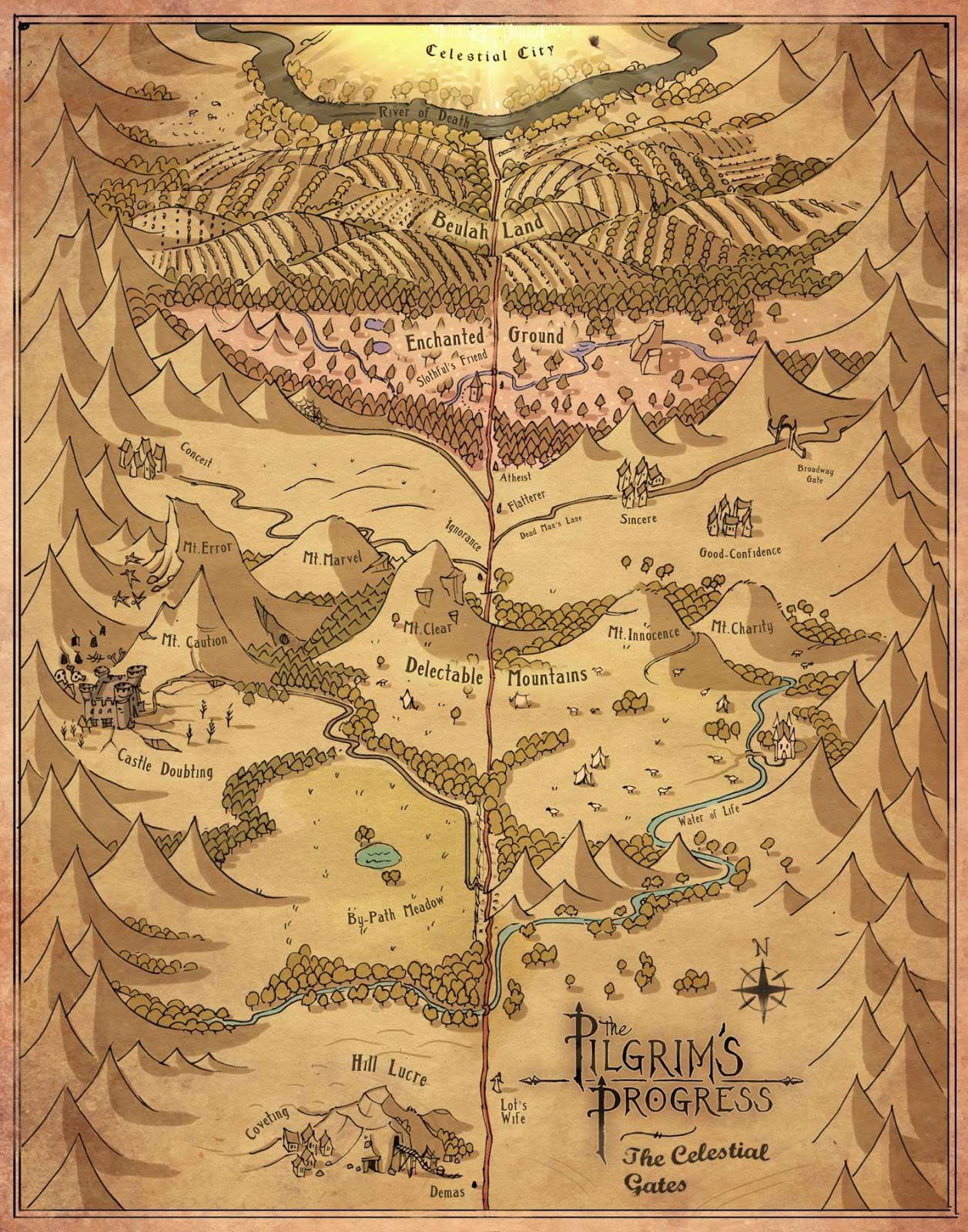

If you want to get bang up to date, created by Pixar animator Garrett Taylor, another straight pathed map runs vertically through four panels, with details from both Part I and Part II. I give you a glimpse of the top panel below, and then encourage you to check out his work at his web gallery, and even buy them as I have, through Etsy I have them printed out to adorn my office door.

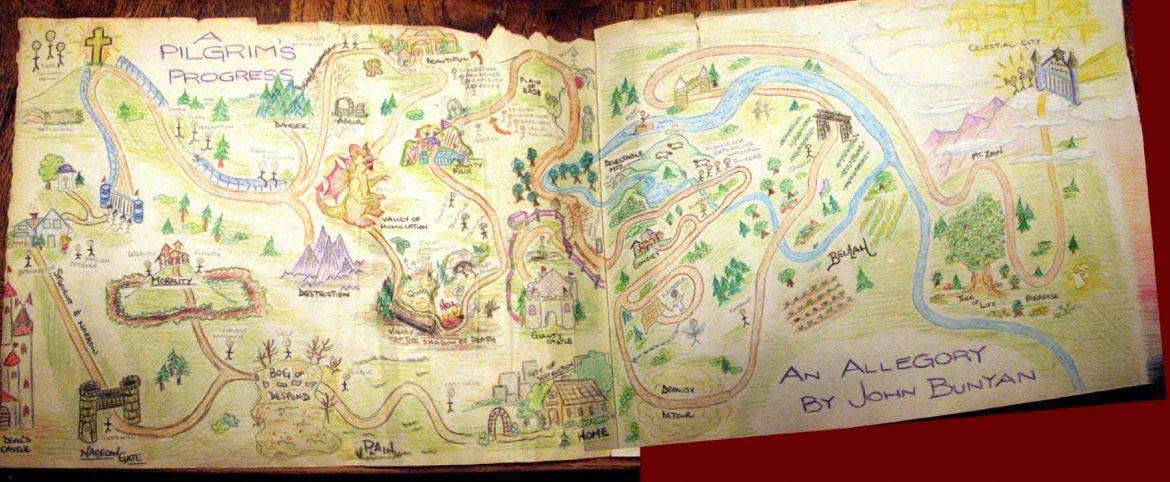

Or of course, you could, like this blogger, just make your own:

Biola University

Biola University

.jpg)