Everyone who is old enough to remember the attacks on the United States has their September 11 story. We all remember where we were, what we were doing, and who we were with when heard about or saw the attacks upon America. We even remember the horrid emotions that we sensed as the events came to pass. That day impacted our lives forever. Yet, with so many people around us hurting much more than we could ever imagine, it became difficult for many people—including myself—to process the impact of that day on our lives going forward.

Twenty years after the September 11, 2001 attacks, I am in the process of re-processing how the residual effects of this day left footprints in my personal life. With the passing of time, I am now able to reflect more fully than in times past and to connect dots that lay detached from one another as a result of never really permitting myself to contemplate the hurt caused by the attacks.

-----

Nuyorican is a term I am not particularly fond of. However, it has been used for decades to describe people like me: New-York-born, Puerto Rican people. My parents met in New York city in the late 70’s, and I was born to a Puerto Rican father and a half Puerto Rican, half Cuban mother in 1980.

My family moved out of New York City in the 80’s searching for a better life. We landed in Lacey Park, PA—a housing sector on the outskirts of Philadelphia with plenty of other Puerto Ricans just like us. However, most of my family, on both sides of the family, stayed in New York City and the surrounding areas.

Thus, my personal distress on September 11, 2001.

I was in college at West Chester University of Pennsylvania on September 11, 2001. I remember getting ready for class relatively early in the morning and hearing murmuring about something happening in New York City. Much to my embarrassment, I did not pay the news much mind. After all, I was a two-hour drive from New York City. There was no need to panic. Stuff that might be shocking to people elsewhere happens in New York City all the time. I went about my day as if it were any other.

Coming home from class on the university’s bus, I heard someone mention that one of the World Trade Center towers had fallen. I had seen those towers, so prominent on the New York City skyline, an innumerable number of times as a child while going around the right-leaning bend, heading into the Lincoln Tunnel which leads into midtown Manhattan.

“What does it mean that one of these buildings had ‘fallen’?” I asked myself as I simultaneously disbelieved the report, while knowing that no sane person would joke about such a serious matter. By the time I got back to the campus, the second tower had fallen. There had been other reports of potential attacks. All planes in the United States were being grounded. No one knew the extent of the attacks or who they were coming for next.

Now, the adrenaline kicked in.

Now, I was starting to sense fear and anxiety.

Watching the perpetually telecasted videos of dust-covered pedestrians wandering the streets—some dressed in business attire with bloody noses and others aimlessly running or wandering around with no apparent destination—was like seeing an ominous apocalyptic movie with bad camera work. This never-ending reel of destruction and dread made it appear as though the entire island of Manhattan—if not the entire city of New York and beyond—was in imminent danger of continued attack.

This meant that, for a period of time, I thought impending doom loomed over all of my family in the New York City area. I started to think about all of the people that could have potentially been in danger:

- My aunt, uncle, their grown children (my cousins), and their families, who all lived about two miles from the World Trade Center on the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

- My uncle who served in the New York City Police Department.

- Several other family members who worked or resided in Manhattan, the Bronx, and, even, North Jersey.

- Later, I came to find out that another cousin (by marriage) was in the first Twin Tower that was hit by a plane that morning.

In the first few days after the attacks, it was near impossible to call into New York City. Though I repeatedly tried to get through, it became obvious that we would have to wait to hear from those family members—if they eventually reached out.

We heard from everyone in the course of time. They were all safe.

But the story does not end here.

There is another part of the story that more deeply affected me at a personal level.

-----

“They’re saying that you do not have to go—that, they are not making anyone get on planes these days.”

I looked at Gaby after repeating the gist of what I had just heard from the airline company. I remember seeing some delight mixed with confusion in her eyes.

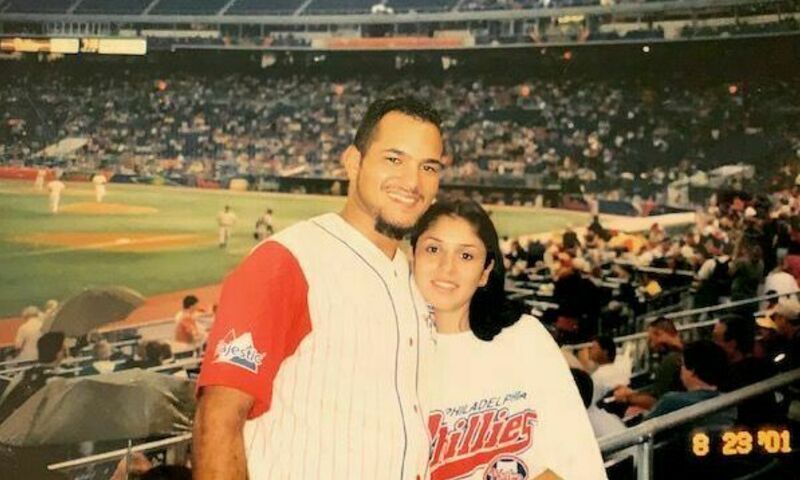

Gaby was my girlfriend in September 2001. We had met and started dating during the previous academic year at the University of Puerto Rico. At the end of that term, Gaby had returned to her country and graduated from the University of Guadalajara in the summer of 2001. Before getting a full-time job, Gaby celebrated her graduation by taking her very first trip to the mainland United States to visit me. We had been dating for almost a year by that time, and it was the first time that my family would meet Gaby. This was a big deal.

But getting her to come was an even bigger ordeal.

- First, we faced the normal pushback that any caring parents would exact upon their young daughter wanting to visit a relatively unknown love interest in another country.

- Second, there was no guarantee that Gaby would be given a tourist visa to be able to enter the United States. It was finally awarded after a long process.

- Third, Gaby was a recent college graduate. I still had two years of college left. In other words, we were completely broke.

But, by the middle of August 2001, we had somehow scavenged enough funds for Gaby to fly from Guadalajara to JFK airport, New York City. After an enjoyable couple of weeks in the USA, the time had come for Gaby to return to Mexico.

Those that experienced long-distance relationships prior to iPhones and Zoom might already be having a visceral reaction at this part of the story. These goodbyes were dreaded because they meant that the relationship would turn back into a voice on the other side of a long-distance calling-card phone conversation for an indeterminate amount of time. Gaby and I seriously had no idea when we would see each other again after her departure.

The date and location of Gaby’s scheduled departure was September 12, 2001, from JFK airport in New York City.

The day before Gaby was to leave the United States to return to Mexico from New York City, the greatest terrorist attack that the United States had ever seen came to pass. All planes were grounded for an undetermined amount of time. Now, we had to find some way to get Gaby home.

At least that’s what she may have thought that I was thinking. I actually had a better plan:

To convince Gaby to stay.

My plan was solidified upon finally getting through to Gaby’s airline company. I called them to ask what their policy was in terms of time limitations for people using tickets that were purchased prior to September 11. The agent with whom I spoke communicated that there was no policy at that time—the airline was not going to encourage people to fly until they felt comfortable getting on a plane again. I thought to myself, “What if people (i.e., Gaby) never want to get on a plane ever again?”

This was my chance to convince her to stay.

I reasoned that if she simply stayed, we would avoid the long, arduous, and costly task of getting her back to the United States in the future. In the ten months after Gaby had left our school in Puerto Rico, there had only been two other occasions in which we were able to spend significant amounts of time with one another. Now, we had a legitimate way to avoid the pain of separating ever again.

I endeavored to persuasively introduce this opportunity to Gaby. She did not have to go back to all of the question marks that were awaiting her in Mexico, like where she would find gainful employment. She could stay with me. I would somehow figure out a way to take care of her—or something like that.

I could tell that the decision was a lot for her.

Gaby asked for some time to think about the issue. Within a day or two, I broached the subject again, hoping that she had begun seeing the world like I had. Gaby’s response shocked me:

“I should go back to Mexico soon. I have to start my life there.”

After those terrible attacks, Gaby was going to almost immediately get on a plane and fly all the way to Mexico?! After all it took her to get to the United States, was she just going to get on a plane and leave in the wake of one of the most horrible modern disasters involving planes?!

I was shocked because it had never crossed my mind that Gaby would strive to start her life without me. As a young man, I could have never envisioned Gaby considering life without me.

I was wrong.

On September 15, 2001, Gaby flew back to Mexico from Philadelphia.

-----

As I process the twenty-year commemoration of the September 11 attacks, and see so many of those horrifying images now reappearing on television and social media platforms, I am vividly—maybe even more now than ever before—sensing the dread that I felt on that day. At the same time, I recognize that the phone calls I received in the wake of the attacks were calls that brought relief instead of sorrow. I lament for those whose worst fears became realities because of these terrorist attacks. Twenty years later, I have not become numb to the images and videos mentioned above. I suspect—better stated, I hope—that I will never get used to those recordings that are now seemingly omnipresent as they recirculate with a vengeance on social media platforms.

Yet, it was not until recently that I realized how different life could have been as a result of this day. Gaby’s rejection of my offer for her to stay in the United States in the wake of the attacks—despite the fact that she returned to many question marks that awaited her as a recent college graduate with no job in Mexico—forced me to recognize my personal naivety and opportunistic egocentrism. My dreams of assuming responsibility for another person from another country at that stage of life were fanciful and arrogant, given the multi-faceted immaturities that were deeply embedded into my character at that time. Gaby was cognizant of this and realized that her life in Mexico presented better opportunities for personal growth.

The inexplicable pain of seeing Gaby leave and wondering when—or even if—I would ever see her again led to a recasting of my vision for the future. Adulthood became prioritized and no longer disparaged as an inevitable decline of the free spirit. Realistically being able to love and care for other people (i.e., Gaby) needed to become a tangible part of my character heading into the future.

I had to wait four months before I saw Gaby again. The occasion was when she visited my family for Christmas. I proposed on Christmas Eve 2001. We only saw each other one more time before we were married on June 14, 2002. The best thing that my wife, Gaby, did for our marriage was to leave me alone in devastating and uncertain times to reflect upon what it was going to take to actually get her to stay.

I am finally grateful for this.

After 19 years of marriage, I eventually connected some of the dots between our personal story and the 9/11 tragedy. I had pushed away my feelings about those horrible days so many times that I could not see these obvious links of how the events eventually brought Gaby and I together in a deeper way than I had hoped for in the moment. I wanted our relationship together to be founded upon a spur-of-the-moment decision amidst a tragic situation. In a way, I guess you could say that I maybe even felt a bit entitled to Gaby’s future (e.g., where and how she was going to live). Thank God, Gaby saw through this.

For several months after she went home to Mexico, both of us had separately considered whether or not Gaby staying with me in the United States was really a good idea.

I am so glad that Gaby eventually decided to stay.

Read more by Dominick on his website.

Biola University

Biola University

.jpg)

.jpg)