This is the third post in a three-part series on the top ten myths about “The Ten Commandments.” Read Part 1 and Part 2.

In the first two posts of this series, I identified 9 myths about “The Ten Commandments” that are pervasive today. You can read those posts here and here. But I've saved the best for last. Today I'm tackling the myth that sent me on a 5-year quest for answers, resulting in a Ph.D. and a published book. I've been waiting 7 years to share this with you!

Myth #10. “The Ten Commandments” prohibit the use of Yahweh's name as a swear word or in false oaths.

Exodus 20:7 reads: “You shall not take the name of the LORD, your God, in vain, for the LORD will not hold guiltless one who takes his name in vain.”

I've asked a lot of people what they think this verse means (we'll call it the “Name Command”). Most people assume that the Name Command teaches that we're not supposed to use God's name as a swear word (as in the flippant, "Oh, my God!" or the harsher “God dammit”). Instead, we should use it reverently. I agree that we should honor God's name by using it reverently, but I do not think to swear words are the problem that the Name Command seeks to address.

Others suggest that the Name Command prohibits false oaths. This interpretation has a very long history. To cite just one example, consider Question and Answer 93 from the Heidelberg Catechism:

Q. What is the aim of the third commandment?

A. That we neither blaspheme nor misuse the name of God by cursing, perjury, or unnecessary oaths, nor share in such horrible sins by being silent bystanders. In summary, we should use the holy name of God only with reverence and awe, so that we may properly confess God, pray to God and glorify God in all our words and works.

However, the Name Command says nothing about oaths or cursing. In fact, it contains no speech-related words at all. Translated simply, it says, “You shall not bear the name of Yahweh, your God, in vain.” Perhaps this is why I've been able to count 23 distinctly different interpretations of the Name Command. It seems like an odd statement –– how does one “bear” God's name? It's no wonder that interpreters have often gone to other passages (either inside or outside of the Bible) hoping for clarification. Most assume that "bear the name" is short-hand for something like "bear the name on your lips," which would be to say the name, or "lift your hand to the name," which would mean to swear an oath.

But there's a much simpler explanation. We miss it because it involves a metaphor that's unfamiliar to us. Shortly after the giving of the Ten Commandments at Sinai, God gave instructions to Moses regarding the construction of the tabernacle, which will house the two stone tablets and the official vestments of the high priest, who will officiate. The article of clothing that is of central importance to Aaron's position as high priest is a cloth chest apron studded with 12 precious stones. These stones are to be inscribed, each with the name of one of the 12 tribes of Israel. Yahweh instructs Aaron to "bear the names of the sons of Israel" whenever he enters the sacred tent (Exodus 28:12, 29). Aaron literally bears their names. He carries them on his person as he goes about his official duties. He serves as the people's authorized representative before God. He also bears Yahweh's name on his forehead, setting him apart as God's representative to the people.

As special as he is, Aaron is a visual model of what the entire covenant community is called to be and do. At Sinai, Yahweh selected Israel as his treasured possession, the kingdom of priests and a holy nation (Exodus 19:5-6). All three titles designate Israel as Yahweh's official representative, set apart to mediate his blessing to all nations. By selecting the Israelites, Yahweh has claimed them as his own, in effect, branding them with his name as a claim of ownership. Because they bear his name, they are charged to represent him well. That is, they must not bear that name in vain. This goes far beyond oaths or the pronunciation of God's name. It extends to their behavior in every area of life. In everything, they represent him. They are his public relations department. The nations are watching the Israelites to find out what Yahweh is like.

Not convinced yet? Look at Aaron's blessing in Numbers 6:24-27. After Aaron's ordination as high priest (where he was clothed with the special garments) and the consecration of the tabernacle and people, his first official act was to pronounce this blessing over the people (see Leviticus 9:22). It's very likely that you've heard the blessing before. It's often used in churches and synagogues:

“May Yahweh bless you and keep you;

May Yahweh smile on you and be gracious to you;

May Yahweh show you his favor and give you peace.”

But have you ever read the following verse? “So they will put my name on the Israelites, and I will bless them.”

You see? It's quite explicit. God put his name on the Israelites as a claim of ownership. They wore an invisible tattoo. They were not to bear it in vain.

Perhaps an illustration will help. Imagine that a group of Biola students head to Disneyland on the weekend wearing Biola swag. Let’s say that they tell dirty jokes and use foul language while waiting in line for rides, leave trash wherever they go and are so intent on running to get to the next ride that they knock people down on the way and don’t stop to apologize. What sort of impression would that give about Biola University? These students may not think of themselves as representatives of the college, but by enrolling as students and wearing the name, they identify with the school. Like it or not, people's impressions of Biola are largely formed by the behavior of its students. (Thankfully, this imaginary story seems very far-fetched!)

So, too, with the people of God. Drawn into a covenant with Yahweh at Sinai, like it or not, they have become his representatives. At the top of the list of covenant stipulations inscribed on the stone tablets are two commands that set the stage for all the others: Worship only Yahweh, and don't bear his name in vain. These two echo the covenant formula repeated throughout the Old Testament: “I will be your God, and you will be my people.” The rest of the 613 commands in the Torah flesh these out in more detail.

And that is what I think the Name Command is all about.

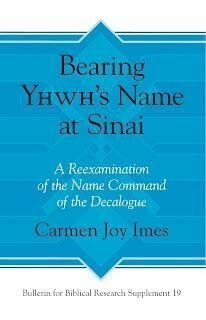

Much more could be said, but this is a blog post, not a book. If you have more questions, you'll find a 186-page justification for this interpretation in my book, Bearing YHWH's Name at Sinai: A Reexamination of the Name Command of the Decalogue. After a brief introductory chapter, chapter 2 engages with other interpretations throughout history, chapter 3 provides extensive word studies of each of the keywords in the Name Command, chapter 4 explores the literary context and chapter 5 delves into conceptual metaphor theory, connecting the Name Command with the high priest and the wider biblical theme of "bearing Yahweh's name."

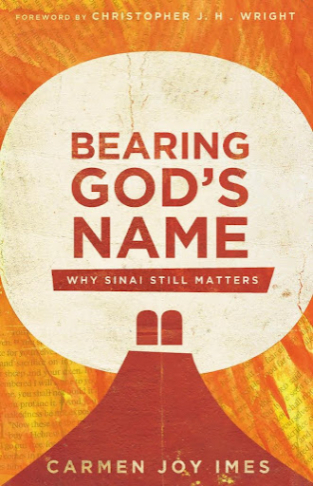

If a dissertation sounds too technical, I’ve written a down-to-earth version of my research just for you! Bearing God’s Name: Why Sinai Still Matters (IVP 2019) traces the biblical theme of bearing God’s name through the Old and New Testaments, showing how followers of Jesus become part of God’s covenant people. If we want to understand our identity and vocation as Christians, I believe it’s essential that we go back to Sinai. Our mission as believers is rooted in Israel’s mission as the people who bear God’s name.

Watch for the biblical theme of “bearing Yahweh's name” as you read the Bible. It's all over the place, once you have eyes to see! You can start with 2 Chronicles 7:14 or Ezekiel 36:20-21 in the Old Testament and 1 Peter 4:16 or Revelation 14:1 in the New Testament.

This post and other resources are available at Carmen Imes’ blog, Chastened Intuitions: Reading Scripture and Reading Life through Trained Eyes of Faith.

Biola University

Biola University

.jpg)

.jpg)