This post is also available in Spanish.

The former Jerome monk, Antonio del Corro, was one of the most important and influential reformers in Spain and throughout Europe, and he continues to be a great example for all Christians of serving God in the middle of many difficulties. In a special way, del Corro encourages immigrants, exiles and refugees with his testimony of persistence and fidelity to the Lord in distant lands. Antonio del Corro was born in Seville, Spain in 1527 and died in London, England in 1591. Antonio del Corro was an excellent theologian, biblical scholar, pastor, teacher and an ardent defender of freedom of conscience. Along with other monks of the Monastery of San Isidoro del Campo, among which were Casiodoro de Reina and Cipriano de Valera, Antonio del Corro fled the Spanish Inquisition in 1557 due to his new faith in Jesus Christ. After wandering for several European countries facing harassment of Protestant groups who were chasing him for not accepting their secondary doctrinal positions, del Corro ended up living in England where he was a pastor and theological censor at the college Christ Church in Oxford

In his Letter to the Lutheran Pastors of Antwerp (Carta a los pastores luteranos de Amberes), originally written in French in 1567, Antonio El Corro tried to mediate the dispute between Lutherans and Calvinists about doctrinal differences, especially about the meaning of the Lord’s Supper. Del Corro makes the purpose of his letter clear in this way: “My brothers, I declare that the intention of this letter is not to enter into a fight or dispute with anyone, I wish that this little admonition may help us all to forget partialities and put us in order for the unity of the Gospel of Christ.” However, unfortunately neither group was satisfied with his conciliatory position and Antonio del Corro was persecuted by both groups throughout his life.

The Letter to the Lutheran Pastors of Antwerp is very personal and Antonio del Corro explains his philosophy of life and ministry in the midst of so many difficulties. Antonio del Corro had to flee his native land and was an immigrant in various countries for the rest of his life. This situation forced him to find refuge in Jesus Christ who, in addition to being his Lord, was his example as an immigrant as he explains in the following way:

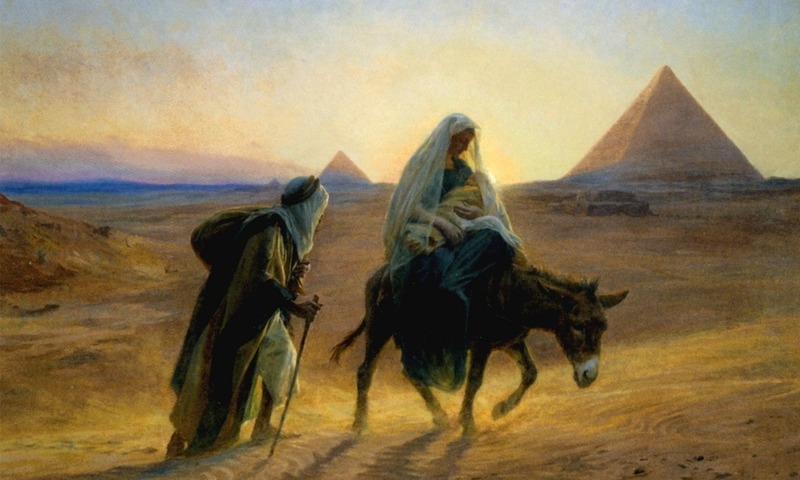

“If we are called foreigners, let us remember that the heavenly father, who has recognized us as his children, is the one who dominates heaven and earth. And wherever we go, we are in our Father's country, we are in our inheritance, following what the Prophet says in Psalm 37, that the righteous will inhabit the earth, and they will be rightful possessors of it. Let us console ourselves that our flight from the country, the absence of the land of our birth, has not been to usurp the possessions or the lordships of another: but only to yield to persecution. Such escapes are not shameful, but honorable, since we are companions of our boss and redeemer, of Jesus Christ, who from his childhood has been a foreigner in the country of the Egyptians, fleeing from Herod's persecution” (p. 89).

Antonio El Corro in his introduction to the Dialogued Commentary to the Letter to the Romans (Comentario dialogado a la carta a los Romanos) dated May 31, 1574 also states that the two most difficult consequences he faced as a result of all theological disputes that accompanied him throughout his life were exile from his homeland and his language. His love for his nation and for his Spanish language were affected by the exile of both. Del Corro explains his situation in this way:

“From this source also came another appendix of the cross, extremely annoying for me, namely, the change of language in teaching, which I endured fairly, but to confess the truth, it with a great effort on my part, as it’s commonly said” (p. 98)

“Meanwhile, the place was not for me the least portion of my afflictions as a language change. For being able to express the sensations of my soul in any way in Spanish, I am forced too often to doubt, to stammer in the language of Rome and to betray my childhood. But nevertheless, since my unpolished speech is not unpleasant for you who value more what is said than what is inflamed with flowers, I am not disgusted or ashamed of the entrusted function” (p. 99).

Antonio del Corro is a model for all those who are immigrants due to different circumstances. His faith and commitment to the Lord made him travel to distant lands and communicate in different languages from his mother tongue. In 1567, more than two centuries before the founding of the United States, Antonio Del Corro recognized that the flight of Jesus and his family to Egypt served as comfort to him as he acknowledged that his Lord was also an immigrant in a strange country. Antonio del Corro was also a masterful educator despite teaching and writing in languages different from his own. Antonio del Corro was never able to return to Spain and was unable to have his writings minister to believers in that country. However, today, more than 400 years after his life and ministry, his main books are already available in Spanish and we can learn from him and imitate his example. All Christians have in Antonio del Corro a role model of fidelity to Jesus Christ who really identifies with our different circumstances, no matter how difficult they may be.

For additional reading, see also Jesus, the Immigrant, by Octavio Esqueda.

Notes

Del Corro, A. (2006). Carta a los pastores luteranos de Amberes. Obras de los reformadores españoles del siglo XVI. Seville, Spain: Editorial MAD.

Del Corro, A. (2010). Comentario dialogado a la Epístola a los Romanos. Obras de los reformadores españoles del siglo XVI. Seville, Spain: Editorial MAD.

Biola University

Biola University

.jpg)

.jpg)