When the magi showed up in Bethlehem, they asked “Where is he who was born King of the Jews?” (Matt 2:2). Why did this question cause Herod to become “alarmed, and all Jerusalem with him”?

“King of the Jews” was not a title used in the Old Testament. It was, however, used by both Jewish and Greek authors to refer to kings of the Hasmonean dynasty (140-37 BC) that immediately preceded Herod. We can get a feel for why this title incited such a response by reading a bit about Herod in the writings of Josephus, a Jewish historian who lived in the first century.

Josephus records a story from Herod’s boyhood. It is likely apocryphal in part, but even if so, it indicates ideas that circulated among Herod’s contemporaries. When Herod was a boy, walking to school, an Essene prophet named Menahem told him that he would one day be King of the Jews. Herod replied that he was only a commoner. At the time, Herod’s father was a powerful advisor to the Hasmonean court, but not from any royal line. Menahem gave Herod a spank on the butt, and told him “Nevertheless you will rule as king… because you have been found worthy by God.” Menahem went on to tell him that he would remember the spank when he became king. But ominously, Menahem prophesied that Herod would “forget piety and justice” and would suffer God’s wrath at the end (Ant. 15.373-377).

Years later, shortly before Herod took the throne, a slur by his chief opponent illustrated the problem of Herod’s legitimacy. Antigonus, the last “King of the Jews” of the Hasmonean dynasty, said that Herod was unfit for rule because he was a commoner, and because he was “Idumean, that is, half-Jewish” (Ant. 14.403). Now, Herod was not half-Jewish in the sense that one parent was ethnically Jewish. Both of his parents were Idumean (Ant. 14.8, War 1.181).

Idumeans were not considered Jewish by descent, but most were Jewish by religion. The Hasmonean king John Hyrcanus compelled many Idumeans, including Herod’s grandfather, to convert to Judaism in the second century BC. (Josephus rejects as propaganda another version of family history, that some of Herod’s ancestors were Jews who returned from exile in Babylon.) Idumeans were circumcised, regarded Jerusalem as their holy city, and worshiped in the Temple (War 4.272, 4.311). But Antigonus was suggesting that as an Idumean, Herod was only “half-Jewish” – perhaps Jewish by religion, but not Jewish enough to rule the nation.

How did Herod finally become “King of the Jews”? It’s a long and complicated history. During a struggle in the Hasmonean dynasty, Herod’s father backed one prince against the other, and invited the Roman general Pompey to come in to assist them. The prince he supported thus became a client king under Rome, with the family of Herod as the power behind the throne. Later, the ousted prince returned with his own army from the Parthian empire, and Herod fled for his life to Rome.

When Mark Antony heard about the situation in Judea, he presented Herod to the Roman Senate and asked them to elect him as “King of the Jews” (War 1.282). The Senate agreed. Herod raised a Jewish army from Jewish people who lived in the diaspora, and he was also given a Roman legion. He succeeded in retaking Jerusalem and becoming King of the Jews. But he was always anxious to legitimize his kingship. Herod married into the Hasmonean family in order to be connected at least by marriage to the established dynasty. He was so determined to cling to his position as “King of the Jews” that he executed his wife and one of his sons that he suspected of plotting against him, and kept another son imprisoned until Herod’s death.

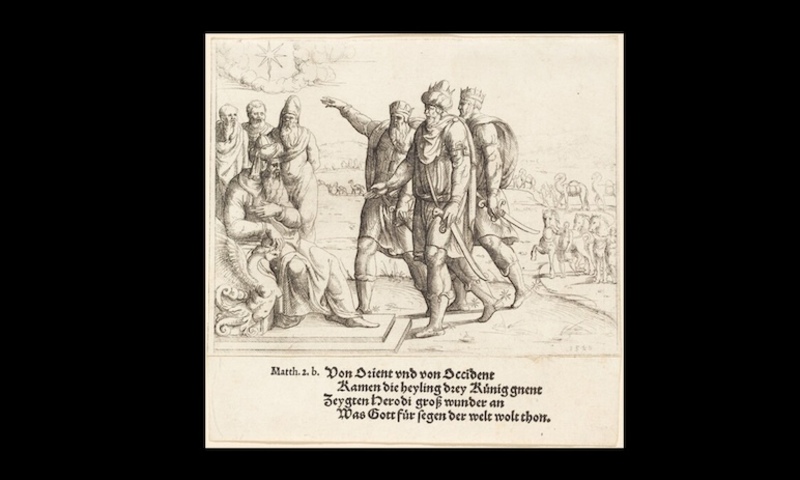

So you may see why Herod was so disturbed at the question the magi asked. Herod was born a commoner, an Idumean, with no claim to the throne. He was by no means “born King of the Jews.” He was only “King of the Jews” by decree of the Roman Senate. Perhaps his sons could claim to be “born King of the Jews” – but they had been born nearly twenty years before. Herod believed in omens and consulted with Essene prophets, so he may well have believed that the wise men knew something from their stargazing.

Herod’s attempt to kill “the one who was born King of the Jews” failed, of course. Later, the accusation that Jesus claimed to be a king would be the official charge to get him executed (Matt 27:11, Luke 23:2). The soldiers mocked Jesus as “King of the Jews” (Matt 27:29), and the charges against Jesus written on his cross were “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews” (Matt 27:37, John 19:19). Herod tried to get the title “King of the Jews” by Roman decree and by conquest. Jesus was declared “King of the Jews” at the cross.

Biola University

Biola University

.jpg)

.jpg)