My oldest turned fifteen a few months ago, and this summer he’s working through the California DMV’s approved online drivers education curriculum. Naturally, this got me thinking about hope and two kinds of Christian pragmatism — only one of which we should embrace.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), part of the Department of Transportation, is responsible for standards around vehicle safety and fuel economy, and generally making federal roadways a safe place to be. As part of this, the NHTSA offers advice and guidance to drivers about safe driving habits.

In perhaps a poignantly useless way of doing this, the NHSTA publishes little pamphlets that they post to their website. Among them are this eye-wateringly designed monstrosity on driver distractions, a missing document on seat belt use (LOL) and this hilariously ancient WordPerfect-looking doc on perception.[1]

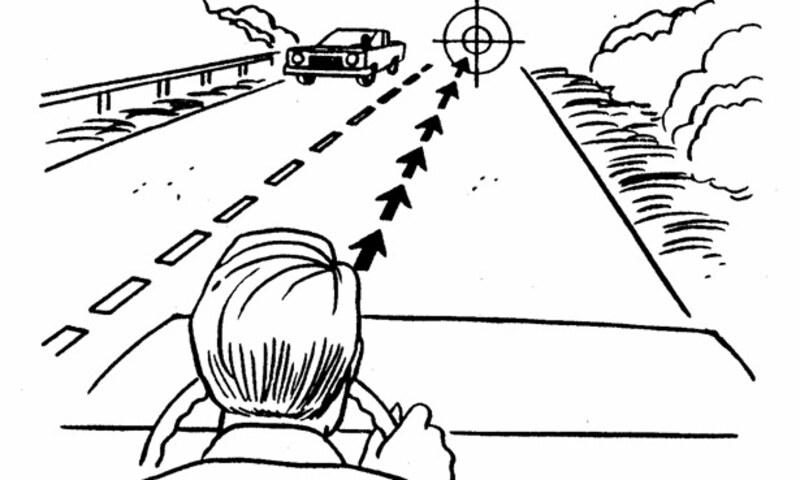

The NHTSA’s annual budget was $1.3 billion in 2023, but that doesn’t stop it from recycling some incredible graphics, like this gem from the perception document:

Of course, the advice implicit in this graphic, which comes to us from the age of rectangular cars, is both excellent and timeless: don’t look at your hood or the road right in front of your car. Keep your eyes up, focused down the road. Here’s the text explanation, positioned weirdly far away from the graphic:

Look ahead—In order to avoid emergency braking or steering, you should look well down the roadway to the end of the travel path. By looking well ahead you can operate a vehicle more safely…and allow yourself time to see better around your vehicle and along the side of the road. Looking well down the travel path will also help you to steer with less weaving.

This tip — in all it’s bolded italic glory — is, of course, as helpful today as it was back when everyone drove a mid-80s Crown Vic or Cutlass Supreme. Look ahead. Focusing on the road immediately in front of your car or — heaven forbid — staring at your instrument cluster, is a recipe for some terrible, dangerous driving. That way lies disaster. Instead, we should look far down the road.

Presumably, my son’s drivers education will talk about this. I certainly will when it comes time for him to actually get behind a wheel. And while looking ahead seems both obvious in the abstract and natural in practice to me now — I’ve been behind the wheel for well north of half a million miles, and not once have I collided with another vehicle while moving forward[2] — it wasn’t so obvious to 14-year-old me. It was something I had to learn.

Switching gears, let’s talk about Christianity and pragmatism.

It’s common to believe, at least implicitly, that faith has to work. That faith has to be beneficial for me and my neighbors, for our communities, for our culture.

There is a sense in which this is pretty obviously true. By faith in Christ we are saved from sin and death and brought into the life of God through the indwelling of the Spirit. If that ain’t workin’ I don’t know what is!

But there’s a temptation in this idea that faith works. The temptation is to think that my present difficulty — whether that’s suffering, poverty, sickness, communal strife … whatever seems to be getting in the way of the goodness or fulfillment of our presentlife or livelihood — ought to be dealt with, more or less immediately, through faith. The worst versions of this are various prosperity gospels. Most of us aren’t so tempted by those.

More subtly, though, many of us are tempted, often unconsciously, to view any kind of psychic suffering as a signal that our faith is useless, or at least not bearing fruit. And this can lead us to think that God is not there, or that he doesn’t care. In my own life with Jesus this has been a regular, if not constant, reality. There are some periods where the temptation is more acute, and others when it fades into the background, idle for a time.[3]

I’m not alone, of course. C. S. Lewis, in the wake of losing his wife, Joy, describes his experience of grief, and of his search for consolation, like this:

Meanwhile, where is God? This is one of the most disquieting symptoms. When you are happy, so happy that you have no sense of needing Him, so happy that you are tempted to feel His claims upon you as an interruption, if you remember yourself and turn to Him with gratitude and praise, you will be — or so it feels — welcomed with open arms. But go to Him when your need is desperate, when all other help is vain, and what do you find? A door slammed in your face, and a sound of bolting and double bolting on the inside. After that, silence. You may as well turn away. The longer you wait, the more emphatic the silence will become. There are no lights in the windows. It might be an empty house. Was it ever inhabited? It seemed so once. And that seeming was as strong as this. What can this mean? Why is He so present a commander in our time of prosperity and so very absent a help in time of trouble?[4]

I have sympathy with Lewis here, and with my past self. In some sense, I think it’s right and good to experience a certain amount of tension between our present reality, both internally and externally, and our faith in God. The world is not how it ought to be.

At the same time, I do think the idea that our faith should prevent this sort of thing is misguided. Faith is not intended to work in this sense.

Hebrews 11 metaphorically screams this at us. After recounting the faith of Abraham, Moses, and few others, and the incredible things God did through them, the author goes on:

And what more shall I say? For time would fail me to tell of Gideon, Barak, Samson, Jephthah, of David and Samuel and the prophets — who through faith conquered kingdoms, enforced justice, obtained promises, stopped the mouths of lions, quenched the power of fire, escaped the edge of the sword, were made strong out of weakness, became mighty in war, put foreign armies to flight. Women received back their dead by resurrection. (11:32-35)

Now — leaving aside the jarring fact that the author of Hebrews had time to discuss Rahab but not David and Samuel — at this point, I think we’re meant to be thinking, “Al-rightttt. This is awesome. God’s people are WINNERS!” Aaaaaand, that makes what comes next jarring:

Others suffered mocking and flogging, and even chains and imprisonment. They were stoned, they were sawn in two, they were killed with the sword. They went about in skins of sheep and goats, destitute, afflicted, mistreated — of whom the world was not worthy — wandering about in deserts and mountains, and in dens and caves of the earth. (11:36-38)

Whelp. That took a turn…

But the author of Hebrews goes on, and this is the bit that really gets me, that I think shows the lie in the idea that faith ought to work like it did for those of God’s people who conquered kingdoms and obtained promises:

And all these [I say again: ALL these], though commended through their faith, did not receive what was promised, since God had provided something better for us, that apart from us they should not be made perfect. (11:39-40)

Implicit in there is the idea that the promise of faith had not been received prior to the Incarnation of the Son. He is the promise of our faith. What happens in the day-to-day of this life is not an indicator of the quality of our faith. Our faith is not meant to work in that sense.

What the author of Hebrews is pointing to is the fact that one thing faith supplies for us now, in the present, is hope.

And hope is, I think, the sense in which faith is pragmatic. Notice that this is precisely the point the author of Hebrews makes next:

Therefore, since we are surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses, let us also lay aside every weight, and sin which clings so closely, and let us run with endurance the race that is set before us, looking to Jesus, the founder and perfecter of our faith, who for the joy that was set before him endured the cross… (12:1-2)

Even the joy of Christ was set before him. It had not yet been received as he hung on the Cross. What Christ had, through his faith in the Father, was hope. Hope in a future reality that was merely set before him, hope in his Ascension to be with the Father, at His right hand.

Hebrews describes the future, what is temporally off in the distance, as something far off in the distance spatially:

These [Abel, Noah, Abraham, Sarah] all died in faith, not having received the things promised, but having seen them and greeted them from afar. (11:13)

Faith raises our eyes from the ground right in front of our feet to the finish line. What lies at the finish is the hope of our faith: life with God in the Kingdom of God. What our faith does not do is alter the ground at our feet.

But this raising of our eyes is a robustly practical thing. Driving while staring at your hood or at the road immediately in front of your car is, as the NHTSA points out, a terrible idea. The same goes for our lives in Christ.

This is the sort of Christian pragmatism I can get behind. Christian faith doesn’t make our present lives comfortable or “happy,” it doesn’t eliminate our suffering or help us to win. It isn’t practical like that. But it does supply the resources we need to carry on, to face life with honesty but with perseverance, confident in what we see in the distance.

In other words: that NHTSA perception doc is right. Hope born of Christian faith allows us to avoid emergency braking and steering. It keeps us from weaving. Even as we hit bumps in the road, keeping our eyes up, fixed on “the end of our travel path,” will help us navigate our lives here and now.

This post and other resources are available at https://pancakevictim.substack.com/.

Notes

[1] I have no idea whether it was actually typeset in WordPerfect. I hope that’s obvious.

[2] The only collision I’ve caused was on a one-way street with head-in angled parking on both sides. I happened to be backing out of a spot just as someone immediately across from me was doing the same. My Toyota’s bumper met the driver’s side rear door of her Volvo.

[3] Knowledge for the Love of God is organized around a particularly acute season of wrestling with God on this front.

[4] A Grief Observed, pp. 5-6 in the HarperOne edition printed in 2000.

Biola University

Biola University

.jpg)