The late 1960s marked one of the most tumultuous periods in American history. Anti-war protests reached a fever pitch culminating in a near war-like confrontation at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. At the same time, the successes of the Civil Rights movement were threatened by the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in April of the same year. This underlying cultural friction combined with the sexual revolution and significant increase in access to psychedelic drugs to give rise to an emerging counterculture that rejected what it viewed as mainstream America.

Despite this season of uncertainty and transition, a revival would emerge from the midst of this counterculture that would profoundly remake much of American Protestantism. One of the most enduring legacies of the period was what came to be identified as the Jesus People Movement (JPM) (1).

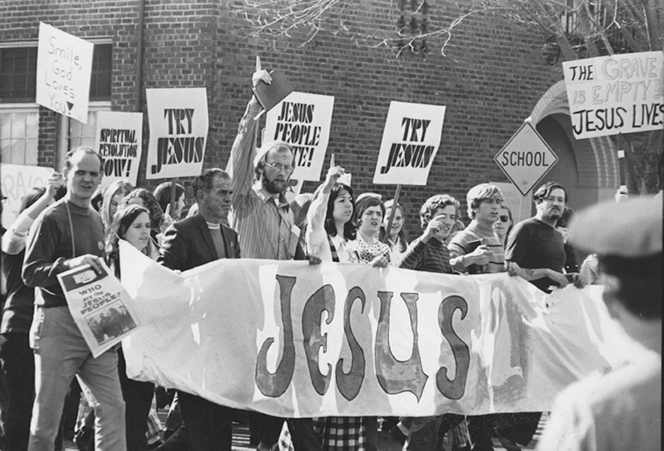

Featured on the covers of magazines like Time and Life, the beliefs and practices of the JPM defined a generation of disenfranchised youth. Many of the forms of worship, approaches to evangelism, and attitudes towards the unchurched that are commonplace in evangelical — and even some Catholic and Mainline Protestant — churches draw their origins from this movement. While capturing such an eclectic and broad movement is challenging, four common features of the JPM emerge.

Built on the Counterculture

An initial step in understanding the Jesus People Movement lies in grappling with the counterculture out of which it sprang. Undoubtedly, few would have picked a culture defined in the popular conscience by its embrace of sex, drugs and rock and roll as the ground out of which revival would grow (2). However, many in the JPM employed the longings of the counterculture and its inability to satisfy as a springboard for the gospel (3). As such, central to understanding JPM lies in exploring not only how it synthesized features of the counterculture with the Christian faith but how these were then utilized to open windows for evangelism (4).

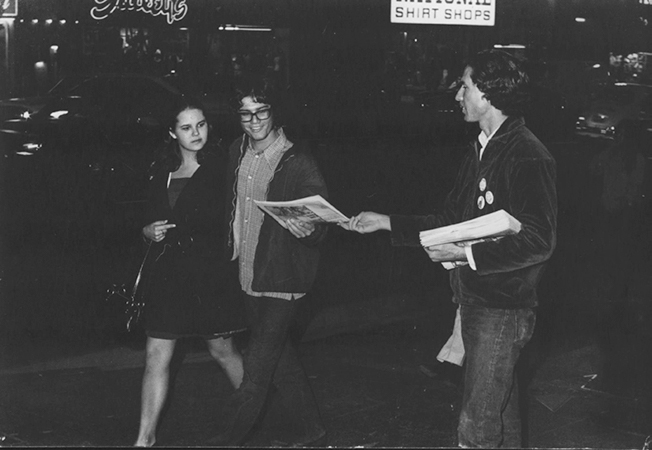

Many of the central innovations of the JPM — such as the coffeehouse movement or local underground newspapers — were built upon models derived from the counterculture. This was most evident in the emergence of Jesus music. What many in the mainstream church had dismissed as the devil’s music, JPM musicians reclaimed as powerful tools for both worship and evangelism. Leading figures such as Larry Norman and groups like Love Song began bending the rock and roll genre to gospel purposes in ways that captured the imagination of young people throughout the country. As historian David Stowe has argued, it was through this popular music that the JPM reinvented much of evangelical Christianity (5).

This synthesis with the counterculture was not always successful. Struggles with drugs and sex often plagued new converts as illustrated in one memorable exchange between David Wilkerson, whose book The Cross and the Switchblade was a central text of the movement, and JPM leaders. While news cameras rolled, Wilkerson berated early leader Ted Wise among others, for their claims that drug use was compatible with their calling as “psychedelic ministers.”6 While examples such as this reveal the inherent messiness of cultural adaption, many of the movement’s most notable leaders emphasized grace for those struggling with the transition between the two worlds.

A Theological Blend of Pentecostalism and Evangelicalism

Tracing the contours of the theology of the Jesus People is challenging. In part due to their own pragmatic tendencies, no substantive theological work was created out of the movement. However, the movement represented a popular blending of key evangelical and Pentecostal doctrines. Historian Richard Bustraan argues that the JPM served as an important catalyst in the blurring between the two streams of Evangelicalism and Pentecostalism (7).

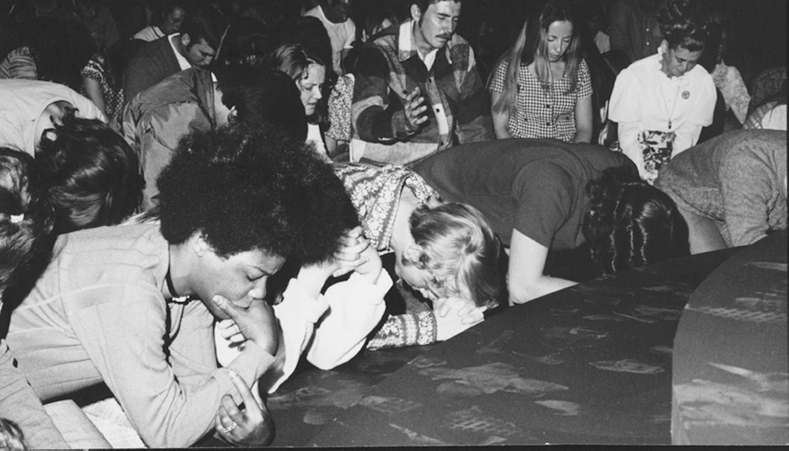

Drawing from Pentecostalism, the majority of the JPM developed a pneumatology that emphasized supernatural experiences, spiritual gifts of prophecy and tongues, and the immanence of God. Prophetic words from God became almost expected as a means of validating authority among early JPM leaders. Reflecting on his early days of street evangelism, Kent Philpott remembered, “I heard God telling me to go to the hippies in San Francisco ... the very next night about eight o’clock I drove into the city, found the Haight-Ashbury District, and started walking around" (8). These supernatural experiences were not only normative across the movement but often served to legitimize JPM ministries in contrast to established churches who, without similar events, were depicted as dead (9).

The evangelical roots of the JPM lay in its devotion to the Bible and premillennial eschatology. Across the various expressions, the JPM emphasized both the authority of Scripture and its accessibility to all believers. Many of its leading pastors and evangelists adopted a simple, verse-by-verse hermeneutic that instilled a belief that all Christians could, through careful reading, likewise understand and apply Scripture (10).

Just as their biblicism synergized well with the countercultural emphasis upon personal investigation and discovery, pre- millennial eschatology layered neatly upon the counterculture’s pervading pessimism about society. The popularity of books like Hal Lindsey’s Late Great Planet Earth reinforced the connection between eschatology and evangelism in the movement. As a result, the imminent return of Christ was emphasized to cultivate a sense of urgency not only into a decision for faith but a commitment of believers to reach the lost (11).

A Spatial Approach to Evangelism

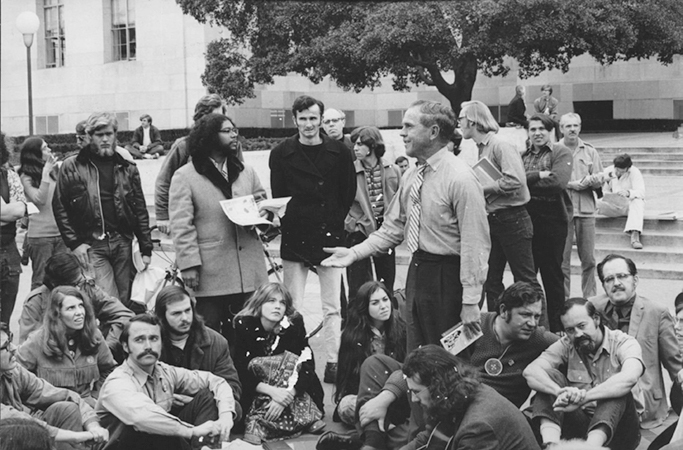

Central to understanding the Jesus People Movement was their singular devotion to and zeal for evangelism. At the core of the movement’s identity was an abiding belief that the gospel was good news for a lost and wandering generation.

The name of the JPM came from its focus: adherents sought to reach people for Jesus. Street evangelism, evangelism bands traveling across the country to share Christ, and a host of evangelists and evangelistic ministries arose from its ranks. Even in their defining slogan — the raised finger and words “one way,” was an acknowledgement that in the midst of such pain, chaos and uncertainty, it was solely through belief in Jesus that people could find the peace and joy they craved (12).

What was particularly innovative for the JPM was in how they thought through the spatial dynamics of evangelism. JPM leaders focused on entering into the spaces occupied by these people on the margins rather than demanding they come to them. The most effective JPM evangelists were those who either adopted counterculture clothing and language, such as Arthur Blessitt, or who were hippies themselves prior to coming to faith, like Lonnie Frisbee.

Recognizing that even many youth had experienced bitter rejection due to their appearance or language, JPM leaders also focused on reinventing religious space. As the JPM spread, coffeehouses became the primary local expression of the movement in cities or towns across the country. While there were a variety of expressions, coffeehouses generally provide informal meeting places for youth to hear local or traveling Jesus music bands and a gospel message by an evangelist or local youth pastor.

JPM leaders also crafted literary space to address the questions and concerns relevant to young people through under- ground newspapers such as the Hollywood Free Paper, Right On and Truth. These papers, built on a tradition established by the counterculture, provided a forum for the issues local JPM leaders believed were being discussed in addition to offering space for evangelistic collaboration.

Many churches adjusted their forms to accommodate the newly converted. Pastor Chuck Smith saw his church explode with hippie conversions, quickly growing from 150 to thousands beginning in 1970 (13). In a famous incident where elders of Calvary Chapel put up a “No Bare Feet Allowed in the Church” sign to protect the carpet in their new facility, Smith told church leaders that if they turned away one person because of bare feet or dirty clothes, he’d personally rip up the carpet and pews. As historian Larry Eskridge points out, these acts by established pastors were pivotal not only for the JPM but for growth of the churches themselves (14).

A Decentralized Movement

The JPM was anything but a cohesive movement. In many ways, it would be more accurate to speak of the JPM as a series of interconnected revivals and evangelistic campaigns rather than a monolithic phenomenon (15). From the late 1960s to the mid-1970s, thousands of churches, parachurch ministries and independent evangelists claimed the mantle of the Jesus People yet massive variations existed across these groups in theology, hierarchy and practice.

Thus, it is hard to encapsulate every element of the movement or its various expressions. In academic and popular histories, the JPM in Southern California have received the bulk of the attention but there are countless other examples. While Calvary Chapel was exploding out West, First Baptist Church of Houston hosted a SPIRENO (Spiritual Revolution Now) crusade featuring youth evangelist Richard Hogue.

Pastor John Bisagno told his people he would rather see hippies sitting on the floor at their church worshiping Jesus than sitting on a park bench smoking pot. The resulting revivals saw over 4,000 young people saved requiring the church to hire a pastor to handle the necessary follow up and baptisms. Colleges became centers for revival. Most famously, Asbury College experienced a revival during a chapel service on February 3, 1970, that lasted 185 hours (16). Asbury students almost immediately began spreading out to testify, sparking similar revivals in surrounding churches and on other college campuses. In one such revival, Asbury students led services at the South Main Church of God in Anderson, Indiana, with services lasting 50 consecutive days. In the same winter, Wheaton College underwent a revival sparked in part by students returning from Christmas vacation who had witnessed the JPM revivals in Southern California (17).

Coffeehouses, communes and evangelistic ministries emerged either as o shoots established by JPM groups out West or as spontaneous revivals. From Jim Palosaari in Milwaukee to John Lloyd in Fort Wayne to David Hoyt in Atlanta, JPM communities sprang up across the United States in the early 1970s and with extremely wide variance in oversight or guidance.

While this decentralization allowed for the broad and rapid diffusion of the movement, it also exposed it to abuse and false teaching from groups such as the Children of God; The Way International; and the Tony Alamo Foundation (18). The inability to regulate one another enabled authoritarian leaders with few options for checks and balances. Thus, when Kent Philpott published a scathing rebuke of the Children of God in the Hollywood Free Paper in the summer of 1971, it did little good (19).

Conclusion

The long-term impact of the JPM, a disparate collection of movements though it was, recognizes entire networks of churches (Calvary Chapels, Vineyard), a revolution in corporate worship music and evangelistic renewal. Ray Ortlund offers the most succinct and personal evaluation of the movement and its legacy:

Woodstock is overrated. The real story of 50 years ago was the Jesus Movement ... [It was a] high-octane, industrial-strength, heaven-sent joy. Now my life mission is for *you* to experience that. You will never again settle for mere fun (20).

ED STETZER, Ph.D., holds the Billy Graham Chair of Church, Mission and Evangelism at Wheaton College, serves as dean of the School of Mission, Ministry and Leadership at Wheaton College, and serves as executive director of the Billy Graham Center.

ANDREW MACDONALD, (M.A. ’12) is the associate director of the Billy Graham Center Institute. He has an M.A. in Philosophy of Religion and Ethics from Talbot School of Theology and is currently a Ph.D. candidate in historical theology at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School.

1. Ronald Enroth, Edward Ericson, and C. Breckinridge Peters, The Jesus People: Old-Time Religion in the Age of Aquarius (Grand Rapids, 1972), 12; Duane Pederson, Jesus People (Regal Books, 1971),34; Richard Ellwood, One Way: The Jesus Movement and Its Meaning (New York: Prentice-Hall, 1973), 59.

2. Erling Jorstad, That New-Time Religion: The Jesus Revival in America (Augsburg Publishing, 1972), 48.

3. Edward Plowman, The Jesus Movement in America: Accounts of Christian Revolutionaries in Action (Pyramid, 1972), 43-44.

4. Marc Allan, What Happened to You? (Enumclaw, WA: Redemption Press, 2016), 54-55.

5. David W. Stowe, No Sympathy for the Devil: Chris- tian Pop Music and the Transformation of American Evangelicalism (Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2011), 8.

6. Larry Eskridge, God's Forever Family: The Jesus People Movement in American (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 50.

7. Richard Bustraan, The Jesus People Movement (Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2014),186-187.

8. Kent Philpott, Awakenings in America (San Rafael, CA: Earthen Vessel Publishing, 2013), 82.

9. Vern Fein, Radical Faith: From the Sixties Counterculture to Jesus (Published by Author, 2019), 53-54.

10. Betty Price and Everett Hullum, Jr., “The Jesus Explosion,” in Home Missions, June/July 1971, 22.

11. Eskridge, God’s Forever Family, 85-86.

12. Don Williams, Call to the Streets (Augsburg Publishing, 1972), 44-45.

13. Edward E. Plowman, The Jesus Movement in America (Pyramid, 1971), 45.

14. Eskridge, God’s Forever Family, 75.

15. Plowman, Jesus Movement, 11.

16. Howard A. Hanke, “God in Our Midst,” in One Divine Moment, ed. Robert E. Coleman (Old Tappan, N.J.: Fleming H. Revell, 1970), 17-25. Coleman included many student testimonies and faculty appraisals in this book.

17. Ray Ortlund Jr. Interview. December 27, 2019.

18. For further information on these and other groups see Enroth, Ericson, and Peters, The Jesus People, 21-66.

19. Ibid., 42.

20. Ray Ortlund, Twitter @rayortlund, 12 August 2019.

All photos made available by Fuller Theological Seminary | fuller.edu

Biola University

Biola University

.jpg)