It doesn't take much to notice that there are deep divisions in our society, and discussions about controversial issues often sound like shouting matches that sometimes turn violent. In other parts of the world, religious differences are often destructive and lead to violence, persecution and sometimes even terrorism. In this first half of a two-part interview, Scott Rae and Sean McDowell talk to internationally known author Os Guinness about his book, The Global Public Square, in which he addresses what he considers the most critical question of the day: How do we get along despite our deepest differences?

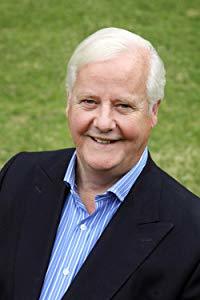

More About Our Guest

Os Guinness is an author, social critic, and great-great-great grandson of Arthur Guinness, the Dublin brewer. Os has written or edited more than 30 books that offer valuable insight into the cultural, political, and social contexts in which we all live. He completed his undergraduate degree at the University of London and his D.Phil. in the social sciences from Oriel College, Oxford.

Episode Transcript

Scott Rae: Welcome to the podcast, "Think Biblically: Conversations on Faith and Culture." I'm your host, Scott Rae, professor of Christian ethics at Talbot School of Theology.

Sean McDowell: And I'm your co-host, Sean McDowell. I'm an author, speaker and apologetics professor at Biola University.

Scott Rae: We're here with our special guest today, Dr. Os Guinness. Os has had a long-time ministry of speaking and writing. He's the author of more than 25 books. He's been a public policy consultant, international relations consultant. He is one of the primary, most insightful people in the Christian community today, on the intersection of faith, culture and public policy.

So Os, we're delighted to have you with us; thanks for joining us today. I want to start out with a couple of things. You've maintained in a lot of your writing that the three most important issues facing the global community are, one is, will the West continue secularizing? Will Islam modernize peacefully? And what worldview will replace Marxism as the dominant one in China?

I know this is hazardous business, but play prophet if you would, for a minute, and 20 years from now, how do you think we will have answered those questions?

Os Guinness: Well Scott, let me make clear, I don't say those are the most important. I'm saying those are three of the issues where a grand global question has a religious dimension. Whereas many people, if you move into international relations, they ignore the religious dimension, which is kind of the X factor. It is so crucial. Now I am not a prophet. Small p or capital P, I am not a prophet.

At the moment though, I would say, about the third one, that the West seems hellbent on severing its roots. That doesn't mean it's going to be secularized totally, not at all. Secularism's powerful, but you can see various new religions. For example, if you go to Silicon Valley, you can see the rise of a new Gnosticism. Mind — boundless, brilliant and infinite. Body — limited and bad. And you get something very close like ancient gnosticism growing out of highly modern stuff from Silicon Valley. So I would say, at the moment, short a revival or the church reforming profoundly, the West looks as if it's on course to sever its roots, rather than recover them.

Scott Rae: All right. And what about Islam, and modernizing peacefully? Where do you think that's headed?

Os Guinness: Well, once again, we can see different trends going in different directions at the moment. In other words, it's not clear. So many people ignore the fact that modernity, fully understood, is the greatest asset corroding traditional certainties, ever. So it's corroding Islam, just as it sadly corroded much of the church. So, you see, more Muslims globally speaking, have been shaken loose from their traditional certainties than ever before. And in parts of the world like, say Indonesia, the largest Muslim majority country in the world, you have millions of them who are shaken loose from Islam, and looking for something different. So we can count on modernity to corrode Islam.

At the same time, in a very different way, we can see many Muslims coming to accept Jesus because of the power of dreams. And clearly, the Holy Spirit is at work, giving them dreams of Jesus. And they are coming to Christ through there, which is incredibly wonderful in a different direction.

But I'm also concerned, we need, as Christians in — not just Christians, as citizens — in America and the West, to teach the new Muslim arrivals what are the core principles of the way we live, such as freedom of conscience. So as it were, as they move from the Middle East to the West, they are now, to put it in their terms, in our tent. If you go to a sheik's tent, you would eat as the sheik eats. And they are in our tent. And here in the West, we believe in freedom of conscience. We believe in religious freedom, etcetera, etcetera.

So notions such as death penalty for conversion is totally out. The blasphemy laws, no. So when they're in our part of the world, we teach them the way we behave, and then they integrate into our world. So there's a number of issues all tied up in that.

One is, modernity. Another is the way the Lord is directly appealing to them. But the third is the way we integrate them into our societies through civic education.

Scott Rae: We'll come back to some of the questions about immigration — in Europe particularly — in just a minute. But you were born in China and spent 10 years of your life there before going to England for education. I know you have a fondness for China. What do you think will replace Marxism as the dominant worldview in China, in the years to come?

Os Guinness: That's not clear yet either. In other words, under Xi Jinping, China has gone towards an authoritarian stance, and many of the churches, Wenzhou and so on, have been really stamped out. No question, that's so.

But talking to friends whom I've met, who are members of the party and Christians, one of my friends very high in the Communist Party, actually said to Hu Jintao, "I've become a Christian, should I resign from the party?" And Hu said, "No. Stay. We need people like you." And there are more and more like that at different levels of the Communist Party.

Now the question, if that keeps developing, in 20 years time, rather like a building eaten by white ants, the Communist Party will collapse, and Christian leadership will emerge. But it's too soon to say.

Scott Rae: And you hold that Marxism has already collapsed as a worldview, in China?

Os Guinness: Marxism, in its traditional Marxist sense, has failed. And the Soviet Union, in its collapse, signaled that clearly. But what you might call a cultural Marxism, that combination of Marxism with an Antonio Gramsci style — who talked of the long march of the institutions, who talk to winning gatekeepers, the people that stride the doorways of influence and power — that is more powerful than ever. And I would say that the left liberalism of the United States is actually very close to a cultural Marxism. So Marxism, in that form, is far from collapsed.

Scott Rae: Say a little bit more about that. Especially as it relates to the United States. You would say the revival of Left Liberalism, not the capital L, or classic Liberalism that we refer to. Distinguish between those two, first of all. And then you've held that, that's on the rise here again in the United States.

Os Guinness: Well I wouldn't say it's on the rise, because it never was popular. In other words, America was a Liberal project, with a capital L. And socialism had never made in-roads into America. So the idea of a candidate like, say, Bernie Sanders, who'd had his honeymoon in Moscow, would have been unthinkable awhile back. And it was always taken that Americanism was the antidote to left-wing socialism.

So it's not a revival of it. It's an emergence of something new. And I argue that it happened in the mid-1960s and the way the feminists, the anti-war movement and others, took over the legacy of civil rights and created a liberal shame. A white shame very often. And that Liberalism project, with a capital L, shifted to a Left Liberalism, which has dominated the universities, dominated the press and media, dominated entertainment in Hollywood, really ever since. So the extremes are way out in the extremes. Like Antifa, or Anti-fa, the Anti-fascist movement. And you remember Huey Long? The old governor of Louisiana?

Scott Rae: Yes.

Os Guinness: He said, "When fascism comes to America, he will be in the guise of anti-fascism." And you can see the things like Antifa are truly the fascism of our day, stamping out freedom of speech and dissent.

Sean McDowell: You've mentioned that the church has moved South from the West, to places like, say, Latin America, Africa and China, there may be more Christians in the years to come than anywhere in the world. What's your sense of the vibrancy of the church in the South? Maybe strengths and weaknesses, and how it's responding to that shift?

Os Guinness: Well the church in the global South is exploding. And the figures are accurate, whether it's Sub-Saharan Africa or Asia, countries like China or Korea, absolutely remarkable and incredibly inspiring. But I always add, the sting in the tail. Much of the global South is pre-modern. And what it's done in the church in the West, is its capitulation to the advanced modern world. Which means, very simply, their challenge is coming because they will modernize.

You take say, you know, industrial revolution came in, in England, with a spinning jenny and things like that. It's coming to Africa with cell phones throughout the villages. But modernity is coming. And the question is, do they have a faithfulness and discipleship able to prevail against the challenges of the modern world, which are coming to the global South? Thank God for their health and vitality today — numerically, spiritually and so on.

But we need to humbly warn them of what's coming, which we didn't do a good job of resisting.

Sean McDowell: And by "we," I assume you mean the West as a whole. Is that correct?

Os Guinness: Yeah.

Sean McDowell: If the West continues to secularize on the path that it's been on, do you see anything that could potentially ground human rights, intrinsic dignity of the human person and individual liberty? If not, how long can the West live off the borrowed capital of Christianity?

Os Guinness: The West is a cut-flower civilization. We owe a lot to the Greeks — philosophy, democracy, science, various things like that. We owe a considerable amount to the Romans — above all, governance, also things like central heating.

But the principle roots of the West go back to the Scriptures and to the gospel. Such as, human rights based in dignity. Freedom based in the notion of people made in the image of God. Equality because we're children of God, equal in his sight; we're not equal in any other way. You look, say, at the French Revolution, where they didn't have God, they held equality and they leveled everyone. And that's what socialism does without a real standard.

And you can see, the West is a cut-flower — America is a cut-flower — civilization. The things that have made America great and so on, the roots have been cut. You cannot ground them in atheism, secularism.

Scott Rae: You had suggested that one of the threats to the church in the global South is, as those cultures modernize, it makes it more challenging for the church to maintain its faithfulness to the Gospel. It's sort of conventional wisdom, I think, in a lot of the circles that we run in that, as modernization occurs, secularization also occurs. How would you assess that secularization thesis that sees those two things working in tandem?

Os Guinness: Well I am dead against the secularization theory. So from Auguste Comte, the sociologist, the father of sociology, for 200 years, you had that secularization theory, even great people like Max Weber believed it. In other words, the more modern we are, the less religious we become. Put simply, religion disappears. That is wrong.

Thank God, in the '60s, it was actually a great sociologist who also happened to be an Anglican minister, David Martin, at the London School of Economics, who challenged that. In other words, the secularization theory is doubly wrong. On the one hand, it's factually wrong. The world is explosively religious as ever. But it's also philosophically biased. In other words, they smuggled in secularist assumptions into the theory and then got their own conclusions out. Garbage in, garbage out sort of thing. So it was doubly wrong.

But that doesn't mean that modernity leaves us all well and fine. Not at all. There are areas in which we have been secularized in a certain sense. I have three examples; I was talking about them in the Biola chapel this morning. But one of them is simply the way the modern world shifts us from a supernatural reality, to a mundane secular reality.

So in the traditional world, what was unseen was not unreal. It was actually more real than the seen. Whereas in our modern world, what is unseen is unreal. We talk about the real world of business, politics, science and measurable outcomes and things, like that's the real world.

No, no. We should be like Elisha, praying that the Lord would open his servant’s eyes so he can see horses and chariots of fire. The unseen world is more real than the seen world. But modern Christians often are atheists unawares. They're operational, functional atheists. So there is a certain secularization, but that's not the Secularization Theory. Religion is never going to disappear. I would argue, even anthropologically, humans need some ultimate source of meaning and belonging, and the deepest source of it all is in fact religion. It might be bad religion, false religion, but they still need it, we would argue, for true faith. But humans will never get beyond some need for faith.

Sean McDowell: Would you say when it comes to secularism, some of the question would be not so much does somebody have a spiritual intuition and need in the modern world, but it's an episteme — a way of knowing. So religion, yes, a ton of people consider themselves religious and it's not disappearing. But is secularism taking over amidst that, the way that people think about the world and their life, and really their worldview?

Os Guinness: Part of the myth, the illusion, of modernity is that the secular worldview is enough. The fact is, it isn't. Take C.S. Lewis, a hardcore atheist. What triggered his search, which took more than 10 years, until he came to Christ? It was what he called being "surprised by joy." In other words, the joy was not pleasure, it wasn't happiness. It transcended, it pointed beyond that. It couldn't be explained by his atheism. And there are a lot of atheists who are jolted into thinking, because secularism doesn't ultimately satisfy.

Now I was arguing earlier that there are many of the big questions you can't answer, such as freedom. Read Sam Harris, one of the new atheists: freedom is an illusion. The very cover of his book shows a picture of puppets. Well that's all we are; we're the victim of our genes. Freud, our childhood. Go back to the Babylonians who were living as stars. Go to the Greeks, it would have been fate. In other words, you're having all these pagan religions, including secularism, and you have determinism, reductionism, fate — not freedom. You only have freedom in the biblical understanding, humans are made in the image of God. A lot of Christians say, "Is God free like that?"

Take the notion of sovereignty. What does sovereignty mean? God can exert his will despite any opposition or interference of any sort; he's sovereign. We're not sovereign, but we are significant. And freedom means we're able to exercise our will, despite interference and restraint. So we are free and responsible, that's why we're morally culpable, and so on. That's a biblical view you cannot find in either secularism, or ancient paganism.

Scott Rae: In your book, The Global Public Square, you point out that one of the most important questions we have to address today is, how can we get along despite our deepest, most heartfelt convictions and differences? Now, your book came out before the current administration is in place. Where do you see the United States on the spectrum? Are you encouraged by where we are moving toward, getting along despite deepest differences? Or, do you think we have moved backward?

Os Guinness: Oh, I don’t think you are moving backward, but I think you're slipping downwards. In other words, America today is suffering its gravest crisis since the Civil War. America is more bitterly divided politically, culturally, religiously, racially, economically than at any time since before the Civil War.

And the question is, what are the deepest differences? It's obviously not Republican against Democrat. It's obviously more than what they say, "Heartlanders against Coastals." Or, "Liberals and Conservatives." And the new difference is, they say, between "Globalists and Nationalists." Well all of those have an element of truth. I don't think they go deep enough.

I think the deepest difference in America is actually a fundamental difference in freedom. A type of freedom which comes from 1776 and the American Revolution, which is decisively shaped by the Scriptures, and the Christian and Jewish view of humanity and so on, and a view of freedom which comes from 1789 and the Enlightenment, and thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau and people like that, that is actually the fundamental difference over which many Americans are fighting.

So it's about freedom. And you can see the irony. Just before the Civil War, Lincoln said, "Everyone's talking of freedom, but they all mean different things." In other words, freedom was different for the Northerner than for the Southerner.

And in the same way today, difference is, our freedom is different for those who are following the American Revolution, and those who, without realizing it, very often are following the French Revolution. And of course, the French Revolution interpreted by Gramsci, Marcuzzo, Foucault and thinkers since then.

Scott Rae: Another good reason to be a continual good student of history.

Os Guinness: Absolutely.

Scott Rae: Let me take this one step further. You suggest in Global Public Square, that the notion of the civil public square is a very important concept for the future and health of our civilization. What exactly do you mean by that? And how would you encourage the institutions to foster that kind of environment?

Os Guinness: Well when you're answering the question, what's the best model, best option for handling diversity, you've really got three models, options around the world. The sacred public square, where one religion is dominant. It might be a mild version. For instance, the Church of England is the established church in England, about as mild as you can get, hanging on by the skin of its teeth to its establishment. Still, an establishment. And those who are non-Anglican, feel second class.

Then you have extreme versions of it — like Pakistan, Iran and Saudi Arabia — where people who don't share the majority faith, Islam, are really in trouble. Or take, say the Muslims in Myanmar, Burma, where they are Muslims in a Buddhist majority country. So I'm opposed to the sacred public square, because it doesn't give justice and freedom for everybody.

The other extreme is the naked public square, where you remove religion altogether. And the simple fact is that 80 percent of the world, at least, is religious. So they're discounted. And then of course you smuggle in secularism to be the dominant faith through the backdoor.

So the civil public square is the alternative to those extremes. But it needs to be unpacked, and it needs to be taught through civic education, so every generation knows what it is, and what they're required to be, as citizens.

Scott Rae: Including recent immigrants. You might even say especially recent immigrants, as well as children?

Os Guinness: Especially. Now if you take the American motto, "E pluribus unum," "Out of many, one," what gave the "unum"? Because America was always very diverse. In the old days it was public school, education and specifically civic education. It was called the melting pot at one stage. You don't like that term, but it was very effective. So people in Europe who thought in groups came and were Americanized, and became individuals.

People in Europe who were thinking of the past tradition, became forward-looking. And so you could go on. People in Europe thought in terms of blood and kinship. Here they talked of beliefs and ideals. The melting pot really did something very powerful. But that's gone.

So now, unless you have civic education for the immigrants, immigration will eventually put more stamp on America than the Revolution. And the Republic as the founders set out will have gone.

Scott Rae: Let me back up just a step. I think when most people think about the term "civility", they think of something really different than what you're referring to. They refer it to as being inoffensive, sort of being perpetually nice. You're referring to something really different.

Os Guinness: People take civility as a matter of niceness, or a fear of being offensive, as you say. It's not at all; it's a duty, a virtue of citizens in a diverse country, who have a respect for people, individual worth. Therefore, for instance, for freedom of conscience. But also respect for truth. Without truth, there is only power. This is what Nietzsche saw very clearly. And this is what post-modernism leads to. You have bullying and domination.

So people who respect people, and people who respect truth, learn how to speak with civility. So we disagree, but always respecting a person and respecting the truth, and arguing persuasively and not coercively.

Scott Rae: Os, thanks for joining us in this podcast today, and appreciate so much your insightful comments, and your wisdom about the challenges that the church faces in our modern world.

Scott Rae: This has been an episode of the podcast, "Think Biblically: Conversations On Faith and Culture." Join us next time as we continue our conversation with Dr. Os Guinness.

To learn more about us, and to find more episodes, go to www.biola.edu/thinkbiblically. That's biola.edu/thinkbiblically. If you enjoyed today's conversation, give us a rating on your podcast app and share it with a friend. Thanks so much for listening and remember, "Think Biblically. About Everything™."

Biola University

Biola University