In this episode, Sean and Scott talk with Judge Ken Starr and Dr. Thomas Farr about the state of religious liberty today in America and beyond. How concerned should Christians be? What big issues are on the horizon? And how can Christians respond? Starr and Farr bring remarkable perspective and wisdom for thoughtful Christians today.

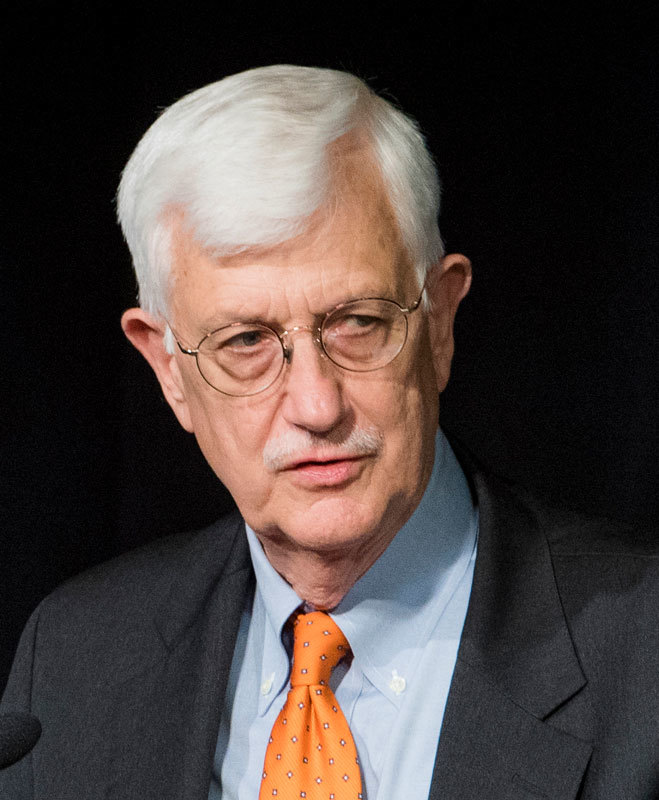

About Dr. Thomas Farr

Thomas Farr is President of the Religious Freedom Institute and Director of the Religious Freedom Research Project at Georgetown University’s Berkley Center. He is associate Professor of the Practice of Religion and World Affairs at Georgetown’s Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service.

A senior fellow at the Institute for Studies of Religion at Baylor University, and at the Witherspoon Institute in Princeton, N.J., Farr received a B.A. from Mercer University, and a Ph.D. from the University of North Carolina.

Dr. Farr served for 28 years in the U.S. Army and the U.S. Foreign Service. In 1999 he became the first director of the State Department's Office of International Religious Freedom. He subsequently directed the Witherspoon Institute's International Religious Freedom (IRF) Task Force, was a member of the Chicago World Affairs Council’s Task Force on Religion and U.S. Foreign Policy, and served on the Secretary of State’s IRF working group.

Dr. Farr trains American diplomats at the Foreign Service Institute, teaches at the National Defense University, and is a consultant to the U.S. Catholic Bishops Conference. He serves on the boards of directors of the Institute on Religion and Democracy, Christian Solidarity Worldwide-USA, and Saint John Paul the Great High School; and on the boards of advisors of the Alexander Hamilton Society and the National Museum of American Religion.

Dr. Farr’s major works include World of Faith and Freedom: Why International Religious Liberty is Vital to American National Security (Oxford, 2008); Religious Freedom and Gay Rights: Emerging Conflicts in North America and Europe, co-edited with Timothy Shah and Jack Friedman (Cambridge, 2016); and U.S. Foreign Policy and International Religious Freedom: Recommendations for the Trump Administration, with Dennis Hoover (Religious Freedom Institute, 2017).

A Roman Catholic, he is married to Margaret McPherson Farr. They have three daughters and 10 grandchildren.

About Judge Ken Starr

Ken Starr has had a distinguished career in academia, the law and public service. For six years, he served as the 14th president of Baylor University. He served as both President and Chancellor for three of those years.He currently is practicing law, writing articles of interest and serving as a guest commentator for various news programs.

Prior to his service at Baylor, he served for six years as the Duane and Kelly Roberts Dean and Professor of Law at Pepperdine University, where he taught current constitutional issues and civil procedure. He has also been of counsel to the law firm of Kirkland & Ellis LLP, where he was a partner from 1993 to 2004, specializing in appellate work, antitrust, federal courts, federal jurisdiction and constitutional law.In addition, Ken is a former partner at the law firm of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP.

Ken has argued 36 cases before the U.S. Supreme Court, including 25 cases during his service as Solicitor General of the United States from 1989-93. He served as United States Circuit Judge for the District of Columbia Circuit from 1983 to 1989, as law clerk to Chief Justice Warren E. Burger from 1975 to 1977, and as law clerk to Fifth Circuit Judge David W. Dyer from 1973 to 1974.He was appointed to serve as Independent Counsel for five investigations, including Whitewater, from 1994 to 1999.

Judge Starr previously taught constitutional law as an adjunct professor at New York University School of Law and was a distinguished visiting professor at George Mason University School of Law and Chapman Law School. After graduating from San Antonio's Sam Houston High School, he earned his B.A. from George Washington University in 1968, his M.A. from Brown University in 1969 and his J.D. degree from Duke University Law School in 1973. He is admitted to practice in California, the District of Columbia, Virginia and the United States Supreme Court.

Ken is the author of more than 25 publications. His book, First Among Equals: The Supreme Court in American Life, published in 2002, was praised by U.S. Circuit Judge David B. Sentelle as "eminently readable and informative...not just the best treatment to-date of the Court after (Chief Justice Earl) Warren, it is likely to have that distinction for a long, long time."His recently published book, Bear Country: The Baylor Story, has been praised by Ben Carson as “a candid and humble look at modern day politics in academia.”

Judge Starr has received numerous honors and awards, including the J. Reuben Clark Law Society 2005 Distinguished Service Award, the 2004 Capital Book Award, the Jefferson Cup award from the FBI, the Edmund Randolph Award for Outstanding Service in the Department of Justice and the Attorney General's Award for Distinguished Service.He has received honorary doctoral degrees from Hampton Sydney College, Shenandoah University, and Pepperdine University and has served in leadership roles on many non-profit boards.

Currently, he serves on the Boards of Advocates International, the Supreme Court Historical Society, and the Christian Legal Society. He also serves on the Advisory Board of The House, DC, a faith-based after school program for inner city youth, and as past President of the Philosophical Society of Texas. He previously served on the boards of Baylor College of Medicine and the Baylor Scott & White Healthcare System.

Ken was born on July 21, 1946, in Vernon, Texas, and raised in San Antonio. He and his wife Alice have been married since 1970 and are blessed with three children and six grandchildren. Ken and Alice have supported numerous non-profits and ministries, including helping children with special needs and volunteering many hours in the inner city by teaching and assisting disadvantaged students with summer internships, after-school programs and guidance for financing a college education.At Pepperdine, Ken helped to initiate a global justice program in Uganda and Rwanda.While at Baylor, Ken participated in the Georgetown-Baylor Partnership for the Religious Freedom Project. He also greatly expanded the summer missions programs in Africa and around the world and traveled to Hong Kong and Beijing to develop strategic educational partnerships. Throughout his professional career, he has championed the cause of religious liberty and freedom of conscience for all persons.

Episode Transcript

Scott Rae: Welcome to the podcast, Think Biblically, Conversations on Faith and Culture. I'm your host Scott Rae, Dean of Faculty and Professor of Christian Ethics here at Talbot School of Theology at Biola University.

Sean McDowell: I'm your co-host Sean McDowell, Professor of Apologetics at Talbot School of Theology, Biola University.

Scott Rae: Our guests today are two of the leading figures in the subject of religious freedom, both domestically and internationally. On the domestic side we're with Judge Ken Starr who's a former Solicitor General of the United States, former Appeals Court Judge, former College President. Both these men actually have resumes much longer than we have time to read. Then on the international side, Professor Thomas Farr is with us. He's the Professor of the Practice of Religion and World Affairs at Georgetown School of Foreign Service, Director of the Religious Freedom Research Project at the Berkeley Center at Georgetown. We're so pleased to have both these gentlemen with us today to discuss issues of religious freedom, both in the United States and around the world.

Let me start with this first, to just on a more personal note, tell our listeners a little bit how each of you got as involved as you have been today in the whole discussion and advocacy for global religious freedom.

Thomas Farr: My passage to this issue was an odd one. It was through one of the most secular institutions in America, namely the Department of State. I had the privilege of being a Foreign Service Officer for 21 years. The last assignment I had was the newly created Office of International Religious Freedom. This piqued my interest for a number of reasons, but at the end of four years in that office, I recognized that this fundamental human right called the First Freedom by our founders and through much of our history was not honored around the world, indeed people are dying and suffering because of their religious beliefs and practices, including Christians, but others. Also, I discovered that in our own country what was once known as the First Freedom is not quite what it once was with respect to the culture and the law. I thought, by golly here's a wonderful thing to be involved in.

I should say that a few years prior to this I had come into the Roman Catholic Church and had discovered what I considered to be a magnificent doctrine of religious freedom. Its Latin title tells the whole story, Dignitatis humanae, the dignity of the human person. I'm committed to this professionally as well as because of deep religious conviction.

Scott Rae: Judge Starr, how did you come to this?

Ken Starr: Let me begin by thanking you for this opportunity, and to say that I love Tom Farr and greatly admire his work at Georgetown, and very pleased to say that Baylor University where I was privileged to serve for six years continues to have a partnership with Georgetown and a religious freedom project in particular. But I came to it as a young pup, as a law student, then as a lawyer, very intrigued by religious freedom issues when I saw them arise here in this country. Tom has a global perspective, mine is more domestic. I was intrigued, challenged by the lack of understanding in the law by lawyers and judges in the United States about what the First Amendment rightly interpreted means. It is a pro freedom First Amendment. It is a pro religious freedom First Amendment. Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof. It's all about freedom, but terribly misunderstood. That misunderstanding continues unto this day.

Scott Rae: Spell that out a little bit further if you would. How has the understanding of the First Amendment shifted say in the last 50, 60 years?

Ken Starr: The seeds of the shift come from Mr. Jefferson's unfortunate metaphor of a wall of separation between church and state. We all believe, of course in the freedom of the church. We don't want a Church of the United States, so we give thanks for a First Amendment that flatly forbids it. We don't want a Church of Utah, or a Church of California. Once upon a time, and during the founding of the Republic until 1833, states had, not all, but states had established churches supported by tax dollars. That's not the First Amendment way. It's not now the American way.

We I think moved to a deeper understanding that yes, we need to be doing everything we can to foster and further religious freedom, but then thanks to some unfortunate language and Supreme Court opinions, and I think a few misguided opinions, suddenly the wall of separation started being re-erected, a resurrection as it were, of a wall in ways that I don't think the founding generation would have imagined that there could not be for example, school choice vouchers. Let's argue at a policy level, but the idea that a state cannot in fact provide opportunities for students to attend religious and other schools because of the educational opportunity they provide struck me as, something has really gone awry here. I think we've had unfortunately a deep misunderstanding based upon the Jeffersonian metaphor of the wall. If it has anything to do with religion, then let's build a wall and keep it private.

Scott Rae: Yeah, go ahead.

Thomas Farr: Could I just add to that?

Scott Rae: Please.

Thomas Farr: I, with some trepidation, supplement one of the greatest minds in the United States and the world on what he has just talked about, Judge Starr, and the First Amendment and the meaning of it. Certainly this is a supplement based on my own non-expert exploration of it, but I can tell you this, the words that he just gave you, "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or restricting or prohibiting the free exercise thereof," there was one, at least one other version of that. It was that Congress shall make no law respecting the establishment of religion or prohibiting the rights of conscience. Note the difference. We all support the rights of conscience, but what we put into our Constitution was far more active. It includes the rights of conscience, which is an interior kind of thing.

But free exercise of religion, I am convinced was intended by the founders as precisely the opposite of today's wall of separation understanding. Free exercise of religion means the rights of religions individuals and communities to engage publicly in our political life, in our public policy life. They wanted this for a lot of reasons. One of them is that it restricts the power of government, which is what they were really about at the bottom. This is a precious part, not just of what Christians believe and their desire. This is part of the American democracy. If we lose it, or if we diminish it or allow it to be diminished we do so at our peril as a country, not just as a religious group.

Scott Rae: Correct me if I'm wrong on this, but my understanding of the term, the wall of separation, actually preceded Jefferson by some time. It was coined by the Baptist Roger Williams initially. The purpose or that was not to prevent the church from impacting the state, but to prevent the state from dictating to the church how it was supposed to conduct its worship and doctrine. Am I right about that?

Ken Starr: From polluting the garden. Yeah, Roger Williams had this very capacious view of individual liberty, and thus the idea of the limited state. Mr. Jefferson picked that up in his letter to the Danbury Baptist Association and then the Supreme Court gave it this really powerful life of its own, and led unfortunately to misunderstanding. Sometimes metaphors are obstacles to correct understanding.

Sean McDowell: You made a wonderful case about how important religious liberty is today. How would you assess where we're at in this historical moment? Religions liberty, is it being practiced? Is it under threat? How would you assess where we're at as a country and maybe even beyond?

Thomas Farr: Well, internationally I think it is fair to say from the evidence that there is an international crisis of religious liberty. Nowhere in the world is it practiced perfectly, never has been. But there is, in my view, a perfect storm of resistance to the idea of religious liberty for very different reasons. The Saudis resisted for their reasons. The Chinese, unofficially Atheist country, resists it for their reasons. In the West, I think aggressive secularism has had something to do with the cultural underpinnings of this privatization of religion and religious freedom.

I think that while the violence that we see around the world on religious freedom has not, thanks be to God, been part of our own experience and never will be, I hope, nevertheless this is the country where it has had its highest expression. To lose that would be to lose something precious for all mankind.We actually have a policy, a foreign policy designed to advance religious freedom around the world. Because of this crisis, I have to say, we haven't done a very good job of it. It's a crisis. We have a big responsibility.

Ken Starr: I would add to what Professor Farr has said, that there are as the founding generation foresaw, pockets of oppression even here at home. I think those pockets of oppression are growing. They're growing in number, they're growing in audacity. One might say, "How dare you challenge religious expression, religious practice unless for the most compelling kinds of reasons," and alas, California hasn't been entirely exempt from this move toward oppression. I use that term, actual oppression. Let's stamp out religious expression in the public square and the like. Happily the good news is that overall, overall, the courts have been our friends. Overall. People say, "Oh, you don't know about this." I probably do know about this case and that case where there are exceptions.

But the general rule illustrated time and again, including by the Supreme Court of the United States after a few wrong steps back especially in the 1950s and '60s, the Supreme Court has usually gotten that right over the last couple of decades. I'm very thankful by the way for the appointment, I'm just going to go ahead and say it, of Justice Neil Gorsuch because Justice Scalia needed, we needed him to remain into his 90s but he went home. He was called home. Happily, we have every reason to believe that Justice Neil Gorsuch will likewise be a friend of liberty. We need more friends of liberty on courts around the country, including but not limited to the Supreme Court.

Sean McDowell: Are you optimistic? Are you cautiously optimistic? Are you deeply concerned as you look at trends within say Gen Z and millennials? How would you frame where we're at right now moving forward?

Thomas Farr: Well, as a Christian I know the victory's been one so I'm an optimist.

Sean McDowell: Amen.

Thomas Farr: But, I am very concerned about the decline of religious freedom, less in the law than in the culture in the United States. We were talking about this this morning. In many ways, culture drives the law, and that is appropriate in our system, but the law has dealt some blows. We're seeing this in California. What's really important in my view is for young people, such as the wonderful students you have at this wonderful university, to understand what religious freedom is and why it's important to them. I would say this is true for non-believers. It's about being a citizen of this country, and understanding the interplay of these fundamental rights, and to pull one out is really to harm the whole. I think we've lost that and we need to regain it.

Ken Starr: There's been a terrible decline in civic education in the United States. Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, not in the context of religious freedom specifically, but just more broadly, used apocalyptic language in describing what has happened. She said, "During my lifetime there has been a collapse of civic education in the United States. We have lost at least one generation, understanding the undercurrents, the underpinnings of freedom." The role of Biola University is all the more important and I'm very pleased to know and have watched with admiration what Biola has done, continues to do to be a beacon in the darkness. There is a gathering darkness, and unfortunately even though so many vibrant evangelical churches, other churches around the country are doing extremely well, there's a lack of focus on shall I call it the threat from within. Not within the church so much as just the civic and educational culture has really not served this generation well, and I think the generation before.

Scott Rae: That may go a long way toward explaining some of the stuff that we've seen among some students and millennials who don't seem to appreciate the importance of religious freedom like a generation earlier did.

Ken Starr: They're not learning it in school, so Biola has to be a lighthouse. The other Christian universities have to be, but I also think that we've got to ... By the way, we need to encourage our students to really consider teaching. Teach for America. At least teach for two years. This is not for indoctrination, it's just we need friends of liberty to be in the classrooms of the United States.

Thomas Farr: If I could just add to that, you were kind enough, Dr. Rae, to mention my work at Georgetown. We also have a spin-off of that work called the Religious Freedom Institute. We actually want to take this learning and put it on the ground. We have action teams. We have action teams in the Middle East, South Asia, Southeast Asia, foreign policy. But we also have an American action team and we have something that we have built called the American Charter. It's not a legal document, but it's a restatement of American principles. What we want to do is take these principles and put them back into the public schools in particular, but some of the religious schools can use this as well. These are not claims. These are not religious claims. They are claims about the importance of religion for American society, and therefore the importance of religious freedom, but not just Christianity.

Every religion that has non-violent product claims to make in our society is important to this society. The founders built more than they knew. We are a multi-religious society, but we have many people that we work with that are not Christian. Muslims, Jews, Buddhists, Hindus who get this, who understand this. In fact, on our advisory board we have ... It's almost like a vision of America. There's one of everything, almost. You can't get one of everything. But every one of these people, the Buddhists, and the Jews, and the rest of them support religious freedom from within their own faith tradition as Americans. This is so important that we want people to understand it. This, I should say, as I said before, it includes Atheists.

Religious freedom protects the right not to believe, but it also in protecting the rights of believers to be involved in public life, stabilizes our society in ways that are important for every citizen of this country. This is a version of the argument we can make to the Saudis and the Chinese too.

Ken Starr: May I also make a domestic point, and I don't want to be misunderstood. I'm making a government and government policy point. Elections have consequences. The late Richard Weaver of Leadership Chicago rightly said, "Ideas have consequences," and so do elections. The reason I say that is that the Supreme Court of the United States rejected a position advanced by the prior administration under President Obama, attractive man with very able people around him, but took a position in the United States on religious freedom and specifically religious schools, and the rights of religious schools to determine who will teach, rejected the position of the Obama administration nine to nothing. This is on 5463, nine to nothing. The Chief Justice of the United States, John Roberts and his opinion just were very briefly, describe the position of the United States government, the executive branch as "extreme".

I would say it was extreme hostility to the idea of religious freedom. My dear friends, elections are meaningful. We just are eager as Tom Farr devotes his energy and his effort and his great talent to spreading the word. We need more Paul Reveres out riding around and saying, we need to be sensitive to, aware of these threats to religious liberty. We need to be patriots. We need to be patriots who stand up and be heard for religious liberty.

Scott Rae: We've seen I think in the last two, two and a half years in the aftermath of the Obergefell decision, I know we've sensed here at Biola University, because we've taken a very public stand on marriage and sexuality, that the landscape has changed pretty dramatically since that decision came out. How would you describe, just the threats to religious freedom that you've seen in the last two to two and a half years?

Ken Starr: The law is the law. The law demands respect, but the law also has to respect freedom of conscience. I think that's where the battleground is now, as well as the rights of religious organizations and associations, the right of churches to be true to themselves, to be true to their own heavenly vision of what they were called to do, and to respect that. Those are where the battle lines are right now. Marriage equality is with us, and so what do we do in light of marriage equality by a five to four vote of being with us, but that is the law of the land. So whether one agrees or disagrees with the decision, what do we do now? The point is, we now have to protect freedom of conscience.

Thomas Farr: If I might, this may sound like a disagreement with Judge Starr, and if it does let me urge you to know that I'm not a lawyer and I'm not an expert here, but in the series of decisions that led up to Obergefell, I saw as a non-lawyer, the building of a logic, call it the animus logic. For those that don't know, animus means hatred. The author of the Obergefell decision, Justice Anthony Kennedy has accused people like me of being motivated by hatred against homosexuals. In the Windsor decision, the prior decision that overturned the Defense of Marriage Act, he said that we have a desire to injure, a desire to humiliate, a desire to harm. This is wrong. It is incorrect.

In the same logic that Judge Starr said about elections have consequences, this is the law of the land, but like Roe V Wade, in my opinion, it can be overturned by a Supreme Court that accepts the logic of the Chief Justice who wrote the primary descent to Obergefell. He said, "This court has done this because it has the power to do it." It is nowhere grounded in the Constitution that the court may make such a decision for the American people. Now, if we choose as states to accept same sex marriage, then that is the democratic process. I would urge those who in conscience and with love, understand and advocate for the Christian view of marriage, not to hide under a bushel basket with that, and to express it with love. It is not excluding anyone. It is the Christian understanding and the natural law understanding what marriage is. We have a right to make that case, and I would urge all those who believe in it to make it.

Scott Rae: Follow up on that for both of you, it's often heard in the public discussion on this that religious groups are using the doctrine of religious freedom to mask discrimination. How do you respond to that?

Ken Starr: Discrimination is a very loaded term, and if one is accused of it, one needs to take the accusation very seriously and then to respond thoughtfully. The very idea of the freedom of association, which is implicit and inherent in our constitutional order, it's essentially part of our First Amendment right to peaceable assemble to seek regress grievances from the government, but it's much broader than that. When these issues arose, with respect to the freedom of association, they arose in the Civil Rights era, and the right of the NAACP to protect its own members. One of the beauties of this country is we have the right to form and join associations. It also means that there's also the right to exclude those who don't share in the vision of that particular institution or organization. Thus, the NAACP had every right to say to the KKK, "We don't want your infiltrators in here. We want to protect our books and records and so forth."

The idea of freedom of association needs to be re-understood that this is who we are and this is what we're called to do. I'm sorry if you don't agree with us, but if you don't agree with us there are other associations and opportunities for organizations for you to express your well-considered views.

Scott Rae: I think that's a real, I think a really helpful broadening of the categories on that and to see that as part of a bigger right to free association, which also outlines what it implies in terms of what can be excluded as well.

Ken Starr: Martin Luther King Jr. did not need to permit Atheists or racists into the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Sean McDowell: We're coming near the end of the podcast and I'm wondering if I could ask you one more question. There's a possible landmark religious freedom case that's currently being decided by the Supreme Court of the United States, namely Masterpiece Cake Shop. How would you anticipate the court deciding and the potential implications for religious liberty in America and maybe even beyond?

Ken Starr: For my part, I'm hopeful that the court will rule in favor, not just of religious liberty but freedom of speech. Mr. Phillips is an artist and he chooses as a matter of conscience not to perform services for, for example Halloween celebrants. He views Halloween as essentially demonic, so he won't bake a Halloween cake. We need to protect freedom of conscience in this country as now embodied in what I view as an act of speech and expression. He is an artist. He is creating a work of art, namely his cakes, that he creates as to honor God. We need to protect that. I'm cautiously optimistic that the court will.

Scott Rae: When it comes to the global concern for religious freedom, what are some things that you would recommend to churches, and schools like Biola to be doing to help advance the cause of global religious freedom?

Thomas Farr: First be aware of what's happening out there, not only to your Christian brothers and sisters who by the way are at the top of the list of those who are being persecuted violently around the world numerically. Muslims come in a close second, often in Muslim majority countries where they are disfavored for one reason or another. But there is a terrible global crisis that involves terrible human suffering. Every Christian should pray that this ends, but then they should galvanize themselves, their communities as citizens of the United States to let their congressmen and women know what's going on, to deal in elections to make sure they're elected representatives know what's going on. We have been for 20 years trying to advance religious freedom as a part of our foreign policy. We've not done terribly well at it.

We now have President Trump's ambassador at large, Sam Brownback, former Senator and Governor Sam Brownback, who is really starting off at a run. Support him. Figure out how you can do that. Make sure your member of Congress understands. I'm sorry to say, and I'll leave it at this, he did not receive one vote in the Senate vote from the members of the democratic party of the Senate, not one vote. This has never happened in the 20 years. It has to do with some of the domestic issues that we are discussing. People are suffering and dying. We should do something as the greatest country in the world, more than we're doing.

Ken Starr: Scripture reminds us that we were prepared to do good works. I know we've got two theological hearers, especially with two distinguished theologians-

Sean McDowell: You're welcome to get theological anytime.

Ken Starr: I'll just say it with scripture. "Faith without works is dead." I know the importance of grace. I'm there. We are called upon to act. I agree we're called to pray, to pray fervently, to pray without ceasing, but we are also praying to act. There are many organizations that work in the religious freedom space. The Religious Freedom Institute, very important. Supporting what Biola is doing, you've convened a very important conference here in December. It was a nationally significant conference. Support Biola University with your time, your talent, your treasure. Through local churches, encourage that pastor. Think about these things. We never hear you talk about religious freedom even over a cup of coffee. Don't you understand? This is a threat around the world, that 75% of people around the world live under very harsh oppressive conditions? 75% of the world's people. Let's keep our mission trips going, but let's expand our concern, not only with prayer, but with our actions.

Scott Rae: It's hard to say that you're committed to the centrality of the gospel if you're not also willing to defend the right to proclaim it and to live it out.

Sean McDowell: Judge Ken Starr and Professor Tom Farr, thank you for your time. Thanks for your love for the country for believers and for non-believers, but even more importantly your love for the Lord and commitment to the cause.

This has been an episode of the podcast Think Biblically, Conversations on Faith and Culture. To learn more about us and today's guests, Ken Starr and Tom Farr, and to find more episodes, go to www.biola.edu/thinkbiblically. That's biola.edu/thinkbiblically. If you enjoyed today's conversation, give us a rating on your podcast app and share it with a friend. Thanks for listening and remember, think biblically about everything.

Biola University

Biola University