Issues of race and racial reconciliation are ongoing in many communities. Sean and Scott interview pastor Miles McPherson (The Rock Church in San Diego, California), about his book, The Third Option: Hope for a Racially Divided Nation. Miles refers to himself as a perpetual outsider, as a mixed race individual (Black, white and Chinese ancestry) who identifies as black. Join us as he shares his experience and his solutions to the problems of racial reconciliation.

Episode Transcript

Sean McDowell: Welcome to the podcast, Think Biblically, Conversations on Faith and Culture. I'm your host, Sean McDowell, Professor of Apologetics at Talbot School of Theology, Biola University.

Scott Rae: I'm your cohost, Scott Rae, Dean of the Faculty and Professor of Christian Ethics, also at Talbot School of Theology here at Biola University.

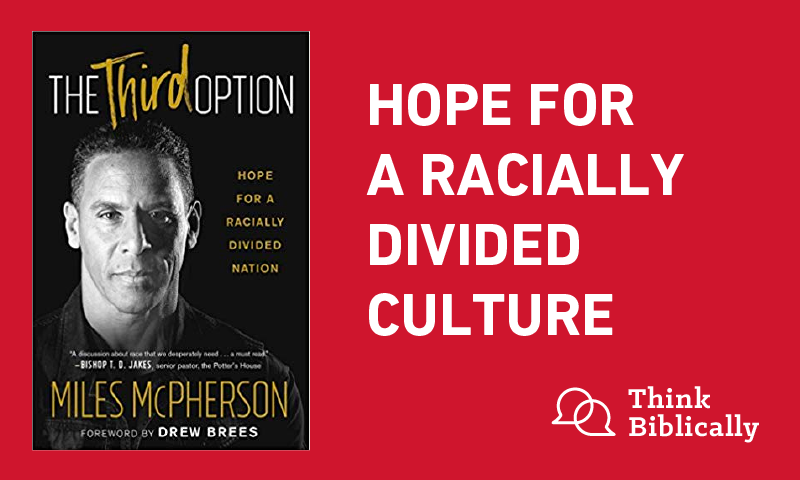

Sean McDowell: We're here today with Pastor Miles McPherson. He is the pastor of the church called The Rock in San Diego, which he founded in 2000. He's the author of multiple books, a popular speaker, but today we want to talk about a book that he's written that is so timely and so powerful called The Third Option. Pastor Miles, thanks for coming on the show.

Miles McPherson: It's my pleasure, and I'm sitting here feeling like I'm ancient hearing you say you're a professor, because I remember when you were a little kid.

Sean McDowell: Oh, my goodness.

Miles McPherson: I'm telling you, some of you who are listening are laughing right now, because me and your dad go so far back. You were in high school I believe.

Sean McDowell: I heard you speak. You came to Julian and gave a talk, and it was about being an eagle, not a turkey, and you know how many talks I've heard in my life.

Miles McPherson: Exactly.

Sean McDowell: I still remember that. So that spoke in volumes to me. Well, we love you. We're grateful to have you on, and let me start by asking you this, of all the topics you could address, why did you choose to write a book in particular on racial reconciliation?

Miles McPherson: Well, a couple reasons. So many pastors write about the same things, prayer, reading the Bible, and I don't know that I have any ingenious idea on how to do that any better. This has been something that I've dealt with my whole life, as most of us have. But I grew up in a racial family. My grandmother was ... I have another grandmother who was half Chinese and Black, and my two grandfathers were Black, and I grew up in a Black neighborhood and went to school in a white neighborhood. Got harassed in the White neighborhood because I wasn't White. Got called names in the Black neighborhood, because I wasn't Black enough.

And so it's always been top of mind, and then I started playing football. We had Black and White guys on the team. We all got along and were united, and now that I pastor a church that is like the United Nations, obviously I see it can happen that people can get along, and we're called to love each other.

And so I wanted to write a book, because writing a book is so much brain damage that I wanted to do something that would address the biggest issue or a big issue that the country was dealing with, because God's truth addresses every issue there is. So this was something that's been on my heart for my whole life.

Sean McDowell: You titled your book I think very interestingly, The Third Option. Tell us what you mean by the third option. What's unique about the approach you're taking?

Miles McPherson: So in every race conversation, and this is true of every argument, whether it be politics, or race, or arguing with your wife, is you have to pick one of two sides. It's us or them, or me versus you, and in our culture, people are being forced to pick a side, one against the other. The third option is that we honor what we have in common, which is the image of God.

And in Joshua, chapter five, Joshua is leading the Israelites into the Promised Land, and he's confronted by the command of the Lord's army, and Joshua asks the commander of the Lord's army, "Are you for us or them, our adversaries," and the commander of the Lord's army says, "Neither. I'm not on either one of your sides. I am the side. It's the third option." The angel was not there to support Joshua. The angel was there to execute the plan of God, and as long as the Israelites agreed with God, God blessed them. But when they didn't, he came against them.

So you need God's idea, and He made us all in His image, and His image is not any inferior or superior one person to another. So this book is how can we get back to where we acknowledge the humanity, the incredible humanity every single one of us have, and all the things that we have in common. We genetically, 99.5% identical genetically. We all want to have relationships. We all want to pursue our dreams, and we're all created to worship God and honor God with our life. So if we can focus on that, we can erase the division we have in our culture.

Scott Rae: I love how you put that. As God says in that passage, "I am the side," and it's not either or, but, "I am the side." I love that part. Tell us a little bit about your own journey to coming to faith, and the unique perspective from which you approach the issue of race.

Miles McPherson: Well, I went to Catholic school for eight years and knew the gospel, and when I was 19 ... I knew about the Bible, and when I was 19, someone shared the gospel with me, and I asked Christ to become my savior. Then five years went by before I got discipled, so I fell back into all the stuff I was doing, and when I was 24 years old, I was playing the San Diego Chargers. I had been doing cocaine all night, and at five o'clock in the morning, I just surrendered my life to Christ and stopped doing cocaine that day.

As far as race goes, because I come from an interracial family, my grandmother is white. She raised us practically, and everybody else was brown, and so we just got along. We understood that people were different shades and different colors, but they were people, and not only were they very close friends, but they were family. So when I saw culture fighting and being divisive, I had the experience that doesn't have to be.

And so all my life, I started a Bible study at my house with teenagers in 1984, 85 or something. We had nine nationalities in my house. And so I've always had a multicultural ministry, and it came natural to me. Then a couple years ago ... Well, more than a couple years ago. But a couple years ago, I started writing this book. But leading up to that, I started thinking we got to do something. There's got to be something that I can write or do to help people get along, and this book opportunity came about.

Scott Rae: It's a really interesting part of your background on this. You sound like from an early age, you were just accustomed to navigating really freely between different cultures and different ethnicities. Yet you refer to yourself in the book as a perpetual outsider. What exactly do you mean by that?

Miles McPherson: Well, when I was a kid, I went to school in a neighborhood where Blacks couldn't live, and so I was an outsider there, because there were three Black kids in my class. Where I grew up, I was light-skinned. So even though I am Black, I got called names as a kid. As a matter of fact, in my neighborhood, I didn't really know a lot of kids in my neighborhood when I was really young, because I went to school in a different neighborhood. So I was an outsider because I didn't know a lot of kids, and then I got called names. So that's what that means.

I have friends in both neighborhoods, and have a lot of good friends of all different ethnicities. But growing up, that was my experience, and part of feeling an outsider in my own neighborhood was I didn't really know a lot of people, and so that fueled that feeling of not feeling like I belonged there.

And I tell you, one of the things that I realized writing this book, and I think this is probably I would think the most pivotal thing for people to get, is that you can be racially offensive without being a racist. Now, we all know if you ask people if they're a racist, some will say yes. Very few. But most people will say no. However, there is so much racial offense going on in our culture, and you can say things, and do things, and think things that are offensive and not necessarily be a racist. You may just be ignorant, or you may say something out of nervousness, or out of fear, or out of hurt.

The reason this is so critical is because the people who are listening right now, if you cannot separate in your mind and heart that you can be racially offensive and not be a racist, if you can't separate those two things because you are adamant you're not a racist, you will be adamant that you're not doing anything offensive, and that breaks down every conversation that people can have, because I have talked to thousands of people in my life about this. All my life have dealt with discriminatory issues, and had arguments with people, and discussions about, "Hey, this was offensive. You shouldn't say this." But the people I'm talking to, often if they can't understand that they could be offensive and not be a racist, they will deny that anything they say is offensive, and then the conversation ends.

And so I think we have to get to a point where we can respect people's feelings, and understand that there are things about how people see the world that are different from ours, and then maybe something we're saying or doing that is actually offensive, and then we can learn without taking on the label of being a racist.

Scott Rae: That's a really helpful distinction, Miles. Can we unpack that just a little bit further?

Miles McPherson: Yes.

Scott Rae: Because I understand how the term racism can be a discussion stopper, and I think we really want to try and get away from that, like you suggest. But how are you defining a racist as opposed to someone who is racially insensitive?

Miles McPherson: Yeah. Racially insensitive ... A racist would be a person who in their heart looks down upon someone of a different ethnicity and thinks they're inferior.

Miles McPherson: Now, there's two kinds of racism I describe in the book. One is institutional, and those are systems that hold people down. For example, my sister when she was going to buy a house, the real estate agent said, "Well, we have to show you an appropriate neighborhood," and this real estate agent that became very close to our family, explained to her that in their practice, they would steer Blacks away from different neighborhoods because they wanted to keep those neighborhoods White. So there's certain types of institutional systems that are unfair to people of color in certain neighborhoods. There's redlining that still goes on, where there's certain neighborhoods where banks won't loan or have higher rates for loaning. So those kinds of things, that's institutional.

Then there is personally mediated racism, where I just want to discriminate against you, individual, one to another, and I'll talk about that in a minute.

And then there is internalized racism, where people who have been discriminated against for so long, they start to believe it about themselves, and they start to look down on their own self as being inferior.

Unconscious biases is where I see you and unconsciously I have this thought about you that you are superior, inferior, scary, I should avoid you, I should automatically trust you. Maybe you're smarter than me, because I heard about your kind of people. And we have labels we put on people almost subconsciously people, and we sometimes don't even realize that we're doing it, and that's where most of us live, because we've been conditioned in the culture about who to be scared of, who to favor, who to think of as more intelligent, or more successful, or more safe.

And so you can come into a conversation, and I have people say to me, "I don't see your color," and though I know what they mean, it's offensive to me, because what you're telling me is that you see red, blue and green, but my color, which brings with it my experience, and my family, and my pain, you just ignore it.

So when someone says that, there's several reasons they would say it, but one of them is I don't want to talk about. You're White just like me. Everything's cool. Let's not talk about race. So, to me, it's like ... You get what I'm saying?

Scott Rae: Yes. And I have changed how I ... I don't use the term color blind anymore for that reason, because I don't want to be discounting the specific context and the situation that a person may have come from and what that involved. So I think those are really helpful distinctions. I think it goes a long way toward just furthering the discussion instead of stopping it to be able to say to someone you made a comment that's racially insensitive, but I don't believe you're a racist. To be able to hold those two things at the same time seems to me to be a really helpful step forward.

Scott Rae: So are you suggesting here that difference is fundamentally one of intent?

Miles McPherson: I would say primarily one of intention, and I would say what you just stated was the definition of a blind spot. It's when your intent is different from your impact, and when you have the intent to build a bridge by saying, "Hey, I have a Black friend," if the impact has a negative effect, there's a blind spot, and the blind spot is maybe that's not the right thing to say, and exactly right.

Sean McDowell: One of things that I loved about your book is you made the point that almost nobody, there's always exceptions, would want to or choose to define themselves as a racist. And yet each of us can be insensitive in different ways, and instead of pointing to other people, we need to take a look at our own lives and ask, "Have I said things? Have I don't things? Have I contributed to this in any fashion?" I was reading your book, and it was really convicting that made me ask myself some of those tougher questions.

How do you give people permission ... Or how do you just process and move this conversation along where people just feel the permission to own that with grace, and yet realize, "Guy, we all have some culpability on this?"

Miles McPherson: Well, the book's intention is not to have people avoid being racist, as much as the intention about being honoring. And so the lessons in the book about racism are saying, okay, here is something that maybe you do or think, and here's another way of looking at it. But now that you know that, here's how you can be honoring towards someone, and it's so much easier to focus on what you will do versus what you won't do, and so that's why I have all the next steps in the book, and the suggestions about next steps.

There's, also, when you have relationships with people, most ... And I say most, 80 to 90% of White/Blacks don't have a White or Black friend that's been to their house, and that they really know really well. If you don't have relationships with people, you're never really going to get to where you deal with those things, because you don't have enough practice. You don't have context.

We all have a social narrative, the story that shapes how we see the world. It's like a prescription of the lens through which we see the world, and it's the story of what our parents told us, what our home was like, what our neighborhood, our high school was like, and all that taught us how to see other people, and most likely, most people are around people who are like them or who have those same beliefs, because they're from the same area. So they see the world through that lens.

Miles McPherson: The problem is there's six billion people, seven billion people in the world, and all have a different lens. Even my brothers who slept in the same room with me have a different lens. And so until you have experience with people and you understand how to talk with people and listen, and listen with an open heart, a humble heart, accepting the fact that I'm a sinner, I'm so imperfect. I don't know everything. But I want to learn about people's pain. I want to learn about how they see the world. I want to learn why they do what they do, instead of getting a nugget from television, or radio, or some blog or Instagram post, and that becomes your truth about a whole group of people.

And so it takes time to be with people, to get to know people, and that's why relationships are so important.

Scott Rae: Wow. So let me take that point a little bit further, if I might. You have several parts in the book where you have different exercises that you describe taking groups through. Fascinating exercises. One of them is what you call the walk in my shoes field trip. Can you explain to our listeners what that is and how it works?

Miles McPherson: Yeah. First, I have to give context. Every single one of us are part of multiple groups, like professors are a group, students are a group, men are a group, White people are a group, Black people are a group, mixed people are a group, and once you identify your group, you give in group bias to the people who are like you. Basically you're more comfortable with people who you spend time with. And so you have more positive assumptions about people who are like you. You receive and give more grace to people who are like you versus people who aren't. That's just human nature.

And so this woman said to me, this person said to me, "You need to get over this race thing," and I said, "Well, you probably spend all your life in your in group, people who are like you. You need to go someplace where you are the other, where you are surrounded with people who are not like you." So she's White. I asked her to go someplace, and that's where you get this field trip exercise. I said, "You should go someplace where you're the only White person, and I want you to answer these questions, what you felt like when you were going? What did you think would happen? How did you think people would treat you? How did people treat you? Did want you fear would happen happen, and had what you feared would happen ever happened in your life?"

It was interesting. When she went, they were a little nervous. They were uncomfortable, and they started reading the minds of people thinking, "They're thinking this about me. They're thinking this about me." All of sudden, now they know how to read people's minds.

It was a very interesting exercise, because that's how people of color live every day, but she didn't know that, because she was around people like her all the time, and when you're around people who are like you all the time and you're not the other, you don't have the perspective of being the other.

Sean McDowell: So it sounds like one of the things you've been saying over and over again is just getting outside of our comfort zones, being willing to listen, go onto people where their turf is at, will just help us be appropriately sensitive to seeing the world as other people do.

Miles McPherson: Yes. And even further than that, when we say we should live in a tolerant culture, God says, "No. I want you to live in a loving culture," and it's one thing to say, "I want to be sensitive and tolerant." The other thing he says, "Listen, I want to know you. I want to love you. I want to bless you. I want to speak a life over you. I want to know how to pray for you," and so it's even more how do we honor, how do I value you as a human being made in the image of God. That means you have the ability to know God, worship God, love like God, and I want to speak life into that, and not just tolerate you and be able to be comfortable and not offend you. That's why it's more offensive than defensive. If I try to just not offend you, we're not really going to have a relationship. But I got to know you and trust you enough to take risks with our conversation and aggressively pour life into you.

So it's more of taking people even past being sensitive to being honoring.

Scott Rae: That's a great point, because I think what that shows us is that being tolerant, being sensitive, that sets the bar pretty low, and you're raising the bar pretty significantly on that, and I think that's consistent with the Bible teaches. It's consistent with what you've said is your main theological lens through which you view people, is people being made in the image of God. I mean that's really consistent with that.

You've got another exercise that I thought was very enlightening in the book, and this goes to the idea of privilege. The idea of white privilege is a particularly sensitive topic. I mean that elicits a lot of emotion when that's brought up.

But help us understand how Christians should think about this idea of privilege. The exercise that I found was so enlightening was the exercise you did with the inmates and the executives that you mentioned in some length in the book. That was fascinating. I'd really like for our listeners to hear about that, too.

Miles McPherson: Yeah. Well, the chapter is called The Privilege of God, because ultimately we receive all our blessings from God, and when you view life as a zero sum game, where for me to win, you have to lose, that means I'm looking for you as the source of my blessing or the source of my curse. Now, God uses people definitely. But that chapter, that's the theme of the chapter.

In the exercise you're talking about, they were inmates lined up shoulder to shoulder facing a group of executives that were lined up shoulder to shoulder, and they were there for a program. It was almost like a shark tank with the inmates, because the inmates were developing businesses that they would run when they got out. And so the inmates were facing shoulder to shoulder facing a group of executives who were shoulder to shoulder, and there was a line in the floor in between them, and they asked the question, "If you had two parents when you grew up, step forward," and most of the executives would step forward, and none of the inmates would step forward, and they step back. "If you ate breakfast before you went to school every day, step forward," and all the executives would step forward, and none of the inmates stepped forward. "If you had 50 books in your house when you were growing up, step forward."

And so it would ask all these questions, and the executives started to realize the advantage that they had over these inmates, and then they asked the question, "If you had someone in your family shot dead or in jail before you got out of high school, step forward. If you were addicted to drugs before you got out of high school. If you had someone in your family addicted to drugs," and they went on these other list of questions, and the executives started to realize these guys never had a chance.

I just got off the plane, and this guy was telling me on the plane that he gave ... This guy on the plane was telling me he told his son, "You don't realize the advantage that you have." The guy on the plane has a business and he's very well-to-do. He said to his son, "You started a mile race a quarter mile ahead of everybody else because of the advantages I've given you," and that's what these executives started to realize, their advantage over the inmates.

Now, it doesn't make those executives racist at all. It doesn't make them bad at all. One of them said, "We just won the birth lottery." They were born into a situation that happened to be better.

Now, the great thing about it was they were there to help those inmates, and so they realized that they had another privilege, which was the privilege of leveraging what they had to help somebody else, and that's exactly what the gospel is about. God blesses us, so we can bless others. And so when you think of privilege, it's not that you're a bad person. It's that you may have started the race a little bit ahead because of the situation you had. It doesn't mean you're bad.

I was talking to a lady in the airport about this, and she said ... We mentioned white privilege, and she said, "Well, I work hard for everything I have." I said, "I don't doubt that you did. But do you think that it has nothing to do with how hard you work? Do you think you would ever be prevented from getting a loan in the bank because you're White," and she said, "Why would I even think that," and I said, "That's exactly my point. You don't have to worry about that. That's a privilege. That's an advantage." It doesn't make her racist at all. It doesn't make her bad at all. However, it doesn't remove the barrier of the people.

There was a leadership developer here in San Diego. His name is Steven Jones, and he wrote an article called "The Right Hand of Privilege," and he basically said that culture is made for right-handed people. The school desks were for right-handed people, because you sat and you put your right elbow on the table, on the desk in school. You can get right-handed golf clubs at any golf shop. You can get a right-handed baseball mitt at any sporting goods store. But if you want to get a left-handed golf club, you have to go to three or four stores or order it online. You can't get a left-handed desk. It's very hard. And so if you're left-handed, you have more hurdles to jump over. It doesn't mean right-handed people are bad. But if you're left-handed, which I am, by the way, you get that disadvantage.

And so if you're right-handed in culture, if culture was made for people who are like you, then you're right-handed. It doesn't make you bad. It just means you have a different ... You have less natural obstacles to jump over.

Sean McDowell: That's a helpful way to look at this. When I was reading your book, and you indirectly invite people to think through the kind of privilege they've maybe had. I wrote a book 12 years ago for students on ethical decisions. So I picked big ethical topics, and when I was reading through your book, it hit me that I didn't even include one on race, and partly it was because where I grew up and my family, I didn't have to see the world through that lens, and it just struck me to think about privilege in a different way, especially based on your experience. So thanks for sharing that and bringing that out in I think ultimately a gospel centered way.

Let me ask you this last question, then we'll wrap up. You're at one of the largest churches in America. So when things happen tied to race in San Diego and beyond, you speak in on this, and there was a very public incident in San Diego in 2016 of a Ugandan immigrant, Alfred Olango, his death, and you gave a sermon right after that. Would you just talk briefly about that sermon, and how you, as a pastor, shepherding 20,000 plus people who had so many different perspectives on this issue, how you tried to bring that together and see at as a gospel issue to bring positive out of it?

Miles McPherson: Yeah. That was a scary week. It happened on a Tuesday, and I preached that Sunday. What made it really scary is I went to the police station that night, and there were about 100 people outside who were very angry, and we ended up going out to talk to them, and a guy cursed my name in front of the group and my church. He said, "Blank the Rock Church, and blank Pastor Miles," and I'm thinking why is he blaming me?

And so that whole week I had that in my head as I was preparing the sermon, and this is where the third option came from, the whole concept, because one side believed that the police was right, and one side believed the police was wrong, and so I presented that to our church, that some of you in here believe the police officer was right, and some of you in here believe the police officer was wrong. But there's a third option. At the time, the third option was what does your heart tell you about the people who disagree with you, because as believers, when I hear decide right or wrong for the police, because we don't know the facts, and all you know is what you saw on television, and there was a blurry camera. Now, you saw enough to have some sort of idea what happened.

However, as a believer, I'm not the judge. But I got to check my heart and evaluate am I honoring God with my thoughts? I challenge people how do you feel about the people who disagree with you, who think opposite of you? That's what you need to be thinking about. Because the altar call, and I'm shaking people's hands, and this guy grabs my hand and he pulls me towards him, and he says, "I'm the guy who yelled at you the other night." He actually came to church and came forward.

So I brought him to the back and I said, "Why did you ..." And he had his mother with him. I brought him in the back and his mother's like, "What happened?" He said, "Well, I was disrespectful to Pastor Miles," and I videotaped his confession, his explanation, and he was just a hurt guy, because there were several shootings in that month, and he says, "I didn't feel like you were saying anything," and his mother said, "What are you talking about? He's been talking about it every time it happened, but you just weren't at church." Here he is judging me, thinking I'm not saying anything about it, but he wasn't at church those days. But he appreciated the sermon.

But the whole thing is when we look on the news and we see people, and this is an appeal to the believers who are listening. If I can say one last point. The greatest commandment is to love God with your heart, mind and soul, and the second is like it, love your neighbor as yourself. When you see someone on television, you see them from a different [inaudible 00:31:28]. If you label them anything less than neighbor, you dehumanize them, and you disqualify yourself from loving them, because they are no longer your neighbor. You can actually go to God and say, "God, I love all my neighbors as myself, but that guy's not my neighbor, so I don't have to love him." It's very subtle, but it's very powerful, and so when you see people on television, and you have these labels, White this, Black this, Arab this, Middle Eastern, whatever you want to call them, immigrant, those labels are giving you subtle permission to discount their value and to allow them to be mistreated, because they're not as human as you.

I think as believers, we have to see people as neighbors. That's it. Everybody's got to be my neighbor, and then I have to ascribe them the love that I deserve and the love that I want. That is what the book is hopefully encouraging people towards, but we can't do that if we don't even know how we're not treating them, how we don't even see them as our neighbor, because we think we see them as human. That's just a that. That's just a that. It's those people. Those titles are dehumanizing.

Biola University

Biola University