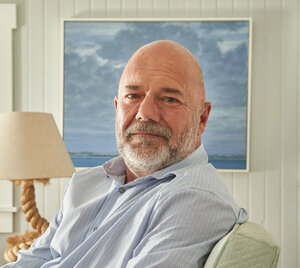

Tim and Rick resume the conversation with Andrew Sullivan on civility and its vital role in a healthy democracy. In this episode, Andrew reflects on the quality of generosity in many Americans, a bright spot in dark times of the argument culture; the discussion then turns to the topic of cancel culture where Andrew candidly shares his experience of being cancelled; and they round out the discussion on two ideas for practicing civility – the method of the dialectic and a lesson from Britain’s House of Commons. This is part 2 of a 2-part conversation with Andrew Sullivan on civility.

Transcript

Rick Langer: Welcome back to the Winsome Conviction Podcast. In the last segment, we had the opportunity to talk with a social commentator The New York Times described as one of the most influential journalists of the past three decades. And that person's Andrew Sullivan. And he's been a former editor of the New Republic, founding editor of The Daily Dish, and has been a regular writer for New York Times Magazine, the Atlantic Newsweek, New York Magazine. And in the first episode, we were able to cover the danger of things like labeling people, how important it is to humanize others, and the secret to creating and maintaining a healthy democracy. We'd like to start this segment on a surprisingly hopeful note.

Tim Muehlhoff: What struck us about Sullivan is that while he's fully aware of the reality of today's argument culture, he remains optimistic. What most strikes him about Americans is not our vitriol, but rather our generosity.

Andrew Sullivan: And I found in my own experience in that 15, 20 year period of going on TV and going on radio shows and going on podcasts and going to colleges and all these talks I did that you meet people where they are. You don't bristle with resentment the minute you see them. You talk to them straight in the eye and you talk about this in a respectful and calm way, they will come and meet you. I was amazed by the generosity of people. Americans, and I say this as an immigrant, they're generally a pretty good, nice people to hang out with. They're civil, they're nice on the whole. There's this dramatic disjunction between the quality of people we know in our own lives and the way people help one another and the way people interact with each other, civility that actually does exist in loads of places all over the place. The small acts of charity that the communities that take care of each other, that goes on all the time in ways that doesn't happen quite as aggressively or as interestingly or as vivaciously in other countries.

Tim Muehlhoff: It's what James Davidson Hunter calls the excluded middle is what you're describing.

Andrew Sullivan: Right.

Tim Muehlhoff: We often focus on the radical hard left, hard that makes us forget about the kindness and the generosity and the humanity.

Andrew Sullivan: Also the practicality of Americans. It's a terribly practical country. So how do we fix this? That's the core American question. It's not what is the meaning of this. I mean, that's more France and so it has these strengths. It's also passionate though. It's a wild and crazy place as well. And we then also injected this new phenomenon called social media in the 21st century, which deliberately is designed to kind of draw your own bile out of you, to display it to the world.

Rick Langer: And reward you when that comes out.

Tim Muehlhoff: Yes.

Andrew Sullivan: And make you feel good because you got more likes now and I got more retweets. And so you get rewarded and it feels good and it's hard to resist because we're all human and that kind of environment sustains it and generates it. But it's not all we are.

Rick Langer: As co-directors of the Winsome Conviction Project, we, like many of our listeners, are concerned about today's cancel culture. While Sullivan shares that concern, he's also surprisingly sees some positives to it.

Tim Muehlhoff: Can we jump back? You did something that I tried to encourage my students to do. You mentioned the pro/con approach. So let's do a test case. Let's do cancel culture, but let's do a pro/con of it because we can kind of see what that could be. The con could be you see cancel culture as a slippery slope that leads to intolerance in democratic societies as people systematically exclude anyone who disagrees with their views. But the pro could be cancel culture serves as a greater purpose in that it holds people to account. So some people have said, we shouldn't call it cancel culture, we should call it call out culture. Could you give your own spin, and I know we're asking you to do this off the top of your head, of what you see is the positive and negatives of cancel culture today?

Andrew Sullivan: Well, public discourse always changes. The way we talk now, the public, we talk about, the words we use are differently where 20, 30, 40 years ago. So that's an evolution that takes place. And so that evolution happens because certain ideas and ways of speaking become unpopular. And because they're dated or they feel... I mean if you look at things you yourself said 20 years ago, it can feel a little ugh. So that's a natural thing and it's a good thing. And some things are the fact that we don't talk about women the way you could listen to this. Or you go back to watch sitcoms in the seventies and it's sort of like, well, some of it was pretty funny actually. They were kind of funny, but they were also terrible. And so you are happy that happened. But that is a natural process that occurs from public taste emerging and evolving.

And also when people do [inaudible 00:05:19] things, they don't get booked back. They become less popular or they just simply fade from view. Or they get criticized harshly criticized, and no one should be in any way opposed to being harshly criticized. That's an incredibly important thing in a society. And people in public life need to be able to grow up, take it on the chin. I don't whine. I've been called [inaudible 00:05:49] but no point in whining. You're out there, you're making arguments, they're going to come back at you.

The difference with cancel culture is very simple. They don't want to harshly criticize me, they want to get me fired. It's when you take the harsh criticism and then turn the criticism of an idea into the moral indictment of a human being. And then seek to punish that human being, publicly punish, publicly shame and find ways to humiliate. And that's a different dynamic. And that's a sort of mob dynamic. And it's a personally destructive dynamic and it's a way to intimidate other people from airing anything different than your point of view. It's a way to chill the discourse artificially. In other words, it's out of bounds. It's basically out of bounds. No, you can argue against this person. You can say this person is such a thing, but you don't create a petition to get that person fired from her job because she did something you don't agree with.

Tim Muehlhoff: As a public figure. Sullivan has often been the focus of those who would like to cancel his voice or views. In this segment he candidly shares his experiences with being canceled.

Rick Langer: But tell us your story. It'd be great for us to hear just a little bit about what that really looked like. Because we tend to see media from afar and you tend to see it from the inside, obviously. Give us a bit of a feeling for how that works.

Andrew Sullivan: Well, here's the thing. I loved working at New York Magazine, It's a great magazine. It has been a great magazine, Not going to bash it now. I did some great pieces with them and I enjoyed it. And my editors there were all fantastic actually, and defended me from this pressure. Until they didn't. I mean, there wasn't actually a specific thing they cited. So I didn't say something that rendered me unsociable with... I didn't write something that they could point to. It was nothing they had as such, but I was clearly not part of their social justice campaign as it were. And so increasingly you would get what I would call a regular edit, then you would get a sensitivity edit. And then you find that your pieces are being edited, are being sent to a sensitivity board of people who will see if they're offended, that person's offended, this person. And then you come back with notes, challenging everything until eventually this goes on and gets worse and worse until as a writer you become completely frustrated. And then you're told you can't use a certain word.

And for a writer to be told you can't use the word, the word was riot, by the way, for what was happening in the summer of 2020 that was not allowed. It was the copy desk that banned it. Because it might mean that this genuine political unrest was being demonized in some way. And I'm like, "I'm a writer, I can use whatever words." Anyway, so it happened kind of cumulatively, and it was coming not from the top but from the bottom. It was coming from junior young staffers, many of whom were part of that Gen Z generation who actually at one point regarded publishing me as rendering their workplace officially unsafe for women to work in.

So they went to HR to complain. So my [inaudible 00:09:35] have to go through this process of this arduous process of having to defend me again and again. And so then I find myself not wanting to put my editors through this process. So then I find myself pulling some punches and then I get fed up with that so I really do a punch and then it gets worse and worse and worse.

And I was going to go, but they had to make a statement about it. And I'm lucky because, and I'm not complaining about myself in this way because what I worry much, much, much, much, much more about is the young 25 year old person who might be thinking of going to journalism and looks at what happened to me and things, "Well, I'm not going to do that. I'm going to stay away from that." Or, "I obviously have to have these views to get into journalism," and then you end up not having good journalism. You end up not having the ability for the average person to read a magazine or a newspaper and see a variety of perspectives so they can make up their own minds, which is how I always understood journalism to operate.

Rick Langer: I think that point you've made it, I think, it's just extremely helpful. I think of people like yourself, Barry Weiss, others who have been... People talk about them being canceled yourself or Barry or whomever.

Andrew Sullivan: Well, hardly though, because Barry and I have more readers than you've ever had.

Rick Langer: Right. And that's exactly the point. So it's great when you think of people like you and Barry because it's like, "Well, they'll do fine." But you're right, the 25 year olds like, "Look, I'm not Barry Weiss. I'm not Andrew Sullivan. So I just can't say those things." And those things then become eliminated invisibly by self censoring before anyone ever has to run them through. I mean, they wouldn't have a chance to be edited as many times as you were. They would've been out the door a long time before because the magazine could cut them and it wouldn't lose anything.

Andrew Sullivan: Right.

Rick Langer: So that's one of the hidden side effects where we say, "Well, this person isn't being canceled." It's like, "Well, that's correct, they aren't." But what about a whole subset of people who are looking at them saying, "If that's what happens to Andrew Sullivan, I'm toast. So I'm not going to say a darn thing."

Andrew Sullivan: Right. Well, that is my concern and I hear it from younger people and people wanting to go into journalism, aren't going into journalism. And what's happened of course is that. But again, in a free society, there are always corrective mechanisms. As long as we have the First Amendment, there are things you can do. So I have started my Substack. Barry's started a Substack. Many, many other writers have started Substacks. They're doing incredibly well. And now the mainstream media's beginning to sort try and copy some of it. And I see a little bit of tempt by some of these big institutions to sort of tack a little bit back towards the center because they realize, in fact, most people regard them now as this kind of tedious critical theory graduate school paper.

And many of us did really well out of it. And now our job now is maybe to hire other people and to encourage people to do this. And so I think, as again, I think as long as the First Amendment exists and isn't reinterpreted to mean, you can't say bad things that hurt people's feelings, which it could be in a couple of generations. But as long as we have it as it is pretty strong, and it's very strong. It's gotten stronger in the last 20 years in many ways in terms of lawsuits and cases that have... Then we are going to be okay. The only thing that can cure the problems of an illiberal society are liberal values and practice of liberal values.

Rick Langer: One of the things we talk about a lot at the Winsome Conviction Project is being able to articulate in a civil way both sides of an issue. Sullivan equally supports its approach and describes an interesting way he's challenged through what he calls the dissent of the week.

Andrew Sullivan: So I'll give you a simple example. I came to this conclusion that, well, what am I doing yelling at people to be more tolerant, liberal. So I need to demonstrate it. I need to actually do it. So that means every week, for example, on my Substack, I have dissents of the week and I air the strongest best arguments from the other side. And I make myself, well, I don't, because I have my buddy, Chris does it. He's the other half of the operation and he will find the best, most persuasive, powerful arguments against mine. And sometimes a few really barbed, nasty things that go in there. I'm not allowed to touch that, he gets to do that. I get to answer.

And you do that every week. And readers get a sense that actually, although you have your point of view, your ultimate loyalty is to the truth which you may not be right about at any moment in time. But that as long as you keep the debate open, the right thing may eventually show up. And that's why I worry in which those people who have defended the freedom of speech, there's an element in which they also want to bully. When I see colleges and legislatures banning books on the right as a response to this, I just want to say, "No, no, no, no, no. This is not how it works. And you are just actually becoming the mirror image of them when you do this." And the key thing is more.

Tim Muehlhoff: Our time closes with Sullivan offering us hope by appealing to a little known fact about Britain's House of Commons, A place frequented by political opponents who bitterly disagree. Well Andrew, what I'm going to take away from this is one, let's humanize the issue. We're talking about people who have struggles, hurts, pains, hopes, fears. Second, I will walk away remembering, do we love our country more than we hate people? And then lastly, what you're saying is let's listen to dissent and let it sharpen us. So your career has been amazing, how long it's been and what an important voice you've been in this country. And we just want to say, at the Winsome Conviction Project that you have caused us to think in very productive ways. Obviously there might be disagreements we might have, but the way you think about the issue has been a great example to us. I just want to say thank you for that.

Andrew Sullivan: You're so welcome. And in that spirit, becoming friends with people you really disagree with is a great thing to do. I mean, I have good friends who I really are very much more left wing than me. And occasionally we have a good old ding dong fight about it, but we still get a beer and we still hang out together. And that's what a liberal society is about. I mean, I love the old British tradition of, you go to the House of Commons, you stand up, they're facing each other and the most hostile way imaginable, right? They're right looking at each other in their faces, yelling, screaming, saying the most extraordinarily damning things about people in the proper language, but no less damning things. And then they'll get a beer afterwards in the House of Commons Pub, which is right there. They have a bar in the Commons. I mean, if you didn't know that, it's like that's where everything happens.

Tim Muehlhoff: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Andrew Sullivan: And that capacity, which was also true of Washington not so long ago.

Rick Langer: Yeah.

Tim Muehlhoff: Yes.

Andrew Sullivan: When Joe Biden would actually hang out with Strom Thurmond, for God's sake. And if anybody could be morally objectionable, it would be Strom Thurmond or Jesse Helms. But the point was you were supposed to deal with it, get along with them, find a way to make a deal. And there was a real passion about that. I mean, it wasn't all lovey-dovey, for God's sake. It was pretty brutal and nasty some of the time, but they got it done because that's what they do.

Rick Langer: Yeah.

Tim Muehlhoff: What a great place to close it. What a great final word to say. CS Lewis, friends look in the same direction, even if they disagree about things.

Rick Langer: Well, thanks a ton for joining us, Andrew. It's been a privilege. We are grateful for you tuning in on the Winsome Conviction Podcast. Would love to have you subscribe at Apple Podcasts or Spotify or wherever it is that you get your podcasts. And also check us out at thewinsomeconviction.com to see some of the resources we'd make available to you for help making our discourse as a nation, as a church, more civil, more loving, and more productive. So thank you for joining us today.

Biola University

Biola University